Pope Benedict XVI

Benedict XVI | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

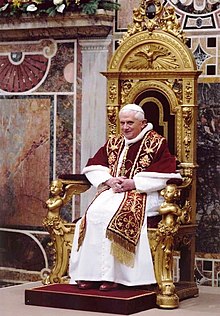

Benedict XVI in 2010 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Church | Catholic Church | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Papacy began | 19 April 2005 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Papacy ended | 28 February 2013 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | John Paul II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Francis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Previous post(s) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ordination | 29 June 1951 by Michael von Faulhaber | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consecration | 28 May 1977 by Josef Stangl | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Created cardinal | 27 June 1977 by Paul VI | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Joseph Alois Ratzinger 16 April 1927 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 31 December 2022 (aged 95) Mater Ecclesiae Monastery, Vatican City | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | German (with Vatican citizenship) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto | Cooperatores veritatis (Latin for 'Cooperators of the truth') | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coat of arms |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Philosophy career | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notable work | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Era | Contemporary philosophy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Region | Western philosophy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| School | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main interests | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notable ideas |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ordination history | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other popes named Benedict | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Papal styles of Pope Benedict XVI | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

Pope Benedict XVI (Latin: Benedictus PP. XVI; Italian: Benedetto XVI; German: Benedikt XVI; born Joseph Alois Ratzinger, German: [ˈjoːzɛf ˈʔaːlɔɪ̯s ˈʁat͡sɪŋɐ]; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as pope occurred in the 2005 papal conclave that followed the death of Pope John Paul II. Benedict chose to be known as "Pope emeritus" upon his resignation, and he retained this title until his death in 2022.[9][10]

Ordained as a priest in 1951 in his native Bavaria, Ratzinger embarked on an academic career and established himself as a highly regarded theologian by the late 1950s. He was appointed a full professor in 1958 at the age of 31. After a long career as a professor of theology at several German universities, he was appointed Archbishop of Munich and Freising and created a cardinal by Pope Paul VI in 1977, an unusual promotion for someone with little pastoral experience. In 1981, he was appointed Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, one of the most important dicasteries of the Roman Curia. From 2002 until he was elected pope, he was also Dean of the College of Cardinals. Before becoming pope, he had been "a major figure on the Vatican stage for a quarter of a century"; he had had an influence "second to none when it came to setting church priorities and directions" as one of John Paul II's closest confidants.[11]

Benedict's writings were prolific and generally defended traditional Catholic doctrine, values, and liturgy.[12] He was originally a liberal theologian but adopted conservative views after 1968.[13] During his papacy, Benedict advocated a return to fundamental Christian values to counter the increased secularisation of many Western countries. He viewed relativism's denial of objective truth, and the denial of moral truths in particular, as the central problem of the 21st century. Benedict also revived several traditions and permitted greater use of the Tridentine Mass.[14] He strengthened the relationship between the Catholic Church and art, promoted the use of Latin,[15] and reintroduced traditional papal vestments, for which reason he was called "the pope of aesthetics".[16] He also established personal ordinariates, for former Anglicans and Methodists, joining the Catholic Church. Benedict's handling of sexual abuse cases within the Catholic Church and opposition to usage of condoms in areas of high HIV transmission was substantially criticised by public health officials, anti-AIDS activists, and victim's rights organizations.[17][18]

On 11 February 2013, Benedict announced his (effective 28 February 2013) resignation, citing a "lack of strength of mind and body" due to his advanced age. His resignation was the first by a pope since Gregory XII in 1415, and the first on a pope's initiative since Celestine V in 1294. He was succeeded by Francis on 13 March 2013 and moved into the newly renovated Mater Ecclesiae Monastery in Vatican City for his retirement. In addition to his native German language, Benedict had some level of proficiency in French, Italian, English, and Spanish. He also knew Portuguese, Latin, Biblical Hebrew, and Biblical Greek.[19][20][21] He was a member of several social science academies, such as the French Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques. He played the piano and had a preference for Mozart and Bach.[22]

Early life: 1927–1951

Joseph Alois Ratzinger was born on 16 April, Holy Saturday, 1927 at Schulstraße 11 at 8:30 in the morning in his parents' home in Marktl, Bavaria, Germany. He was baptised the same day. He was the third and youngest child of Joseph Ratzinger Sr., a police officer, and Maria Ratzinger (née Peintner); his grand-uncle was the German priest-politician Georg Ratzinger. His mother's family was originally from South Tyrol (now in Italy).[23] Benedict's elder brother, Georg, became a Catholic priest and was the former director of the Regensburger Domspatzen choir.[24] His sister, Maria, who never married, managed her brother Joseph's household until she died in 1991.[25]

At the age of five, Ratzinger was in a group of children who welcomed the visiting Cardinal Archbishop of Munich, Michael von Faulhaber, with flowers. Struck by the cardinal's distinctive garb, he announced later that day that he wanted to be a cardinal. He attended the elementary school in Aschau am Inn, which was renamed in his honour in 2009.[26] In 1939, aged 12, he enrolled in a minor seminary in Traunstein.[27] This period lasted until the seminary was closed for military use in 1942, and the students were all sent home. Ratzinger returned to Traunstein.[28]

Wartime and ordination

Ratzinger's family, especially his father, bitterly resented the Nazis, and his father's opposition to Nazism resulted in demotions and harassment of the family.[29] Following his 14th birthday in 1941, Ratzinger was conscripted into the Hitler Youth – as membership was required by law for all 14-year-old German boys after March 1939[30] – but was an unenthusiastic member who refused to attend meetings, according to his brother.[31] In 1941, one of Ratzinger's cousins, a 14-year-old boy with Down syndrome, was taken away by the Nazi regime and murdered during the Aktion T4 campaign of Nazi eugenics.[32] In 1943, while still in seminary, he was drafted into the German anti-aircraft corps as Luftwaffenhelfer.[31] Ratzinger then trained in the German infantry.[33] As the Allied front drew closer to his post in 1945, he deserted back to his family's home in Traunstein after his unit had ceased to exist, just as American troops established a headquarters in the Ratzinger household.[34] As a German soldier, he was interned in US prisoner of war camps, first in Neu-Ulm, then at Fliegerhorst ("military airfield") Bad Aibling (shortly to be repurposed as Bad Aibling Station) where he was at the time of Victory in Europe Day, and released on 19 June 1945.[35][34]

Ratzinger and his brother Georg entered Saint Michael Seminary in Traunstein in November 1945, later studying at the Ducal Georgianum (Herzogliches Georgianum) of the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. They were both ordained in Freising on 29 June 1951 by Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber of Munich – the same man Ratzinger had met as a child. He recalled: "at the moment the elderly Archbishop laid his hands on me, a little bird – perhaps a lark – flew up from the altar in the high cathedral and trilled a little joyful song".[36] He celebrated his first Mass later that summer in Traunstein, at St. Oswald's Church.[37]

Ratzinger's 1953 dissertation was on Augustine of Hippo and was titled The People and the House of God in Augustine's Doctrine of the Church. His habilitation (which qualified him for a professorship) was on Bonaventure. It was completed in 1957 and he became a professor at Freising College in 1958.[38]

Encounter with Romano Guardini

In his early twenties, Ratzinger was deeply influenced by the thought of Italian German philosopher Romano Guardini,[39] who taught in Munich from 1946 to 1951 when Ratzinger was studying in Freising and later at the University of Munich. The intellectual affinity between these two thinkers, who would later become decisive figures for the twentieth-century Catholic Church, was preoccupied with rediscovering the essentials of Christianity: Guardini wrote his 1938 The Essence of Christianity, while Ratzinger penned Introduction to Christianity, three decades later in 1968. Guardini inspired many in the Catholic social-democratic tradition, particularly the Communion and Liberation movement in the New Evangelization encouraged under the papacy of the Polish Pope John Paul II. Ratzinger wrote an introduction to a 1996 reissue of Guardini's 1954 The Lord.[40]

Pre-papal career: 1951–2005

Academic career: 1951–1977

| Part of a series on the |

| Theology of Pope Benedict XVI |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|

Ratzinger began as assistant pastor (curate) at the parish St. Martin, Moosach, in Munich in 1951.[41] Ratzinger became a professor at the University of Bonn in 1959, with his inaugural lecture on "The God of Faith and the God of Philosophy". In 1963, he moved to the University of Münster. During this period, he participated in the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) and served as a peritus (theological consultant) to Cardinal Frings of Cologne. He was viewed during the time of the council as a reformer, cooperating with theologians like Hans Küng[42] and Edward Schillebeeckx.[43] Ratzinger became an admirer of Karl Rahner, a well-known academic theologian of the Nouvelle théologie and a proponent of Church reform.[44]

In 1966, Ratzinger was appointed to a chair in dogmatic theology at the University of Tübingen, where he was a colleague of Hans Küng. In his 1968 book Introduction to Christianity, he wrote that the pope has a duty to hear differing voices within the Church before making a decision, and he downplayed the centrality of the papacy. During this time, he distanced himself from the atmosphere of Tübingen and the Marxist leanings of the student movement of the 1960s that quickly radicalized, in the years 1967 and 1968, culminating in a series of disturbances and riots in April and May 1968. Ratzinger came increasingly to see these and associated developments (such as decreasing respect for authority among his students) as connected to a departure from traditional Catholic teachings.[45] Despite his reformist bent, his views increasingly came to contrast with the liberal ideas gaining currency in theological circles.[46] He was invited by Rev. Theodore Hesburgh to join the theology faculty at the University of Notre Dame, but declined on grounds that his English was not good enough.[47]

Some voices, among them Küng, deemed this period in Ratzinger's life a turn towards conservatism, while Ratzinger himself said in a 1993 interview, "I see no break in my views as a theologian [over the years]".[48] Ratzinger continued to defend the work of the Second Vatican Council, including Nostra aetate, the document on respect of other religions, ecumenism, and the declaration of the right to freedom of religion. Later, as the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Ratzinger most clearly spelled out the Catholic Church's position on other religions in the 2000 document Dominus Iesus which also talks about the Catholic way to engage in "ecumenical dialogue". During his time at Tübingen University, Ratzinger published articles in the reformist theological journal Concilium, though he increasingly chose less reformist themes than other contributors such as Küng and Schillebeeckx.[49]

In 1969, Ratzinger returned to Bavaria, to the University of Regensburg and co-founded the theological journal Communio, with Hans Urs von Balthasar, Henri de Lubac, Walter Kasper, and others, in 1972. Communio, now published in seventeen languages, including German, English, and Spanish, has become a prominent journal of contemporary Catholic theological thought. Until he was elected pope, he remained one of the journal's most prolific contributors. In 1976, he suggested that the Augsburg Confession might be recognised as a Catholic statement of faith.[50][51] Several of Benedict's former students became his confidantes, notably Christoph Schönborn, and a number of his former students sometimes meet for discussions.[52][53] He served as vice-president of the University of Regensburg from 1976 to 1977.[54] On 26 May 1976, he was appointed a Prelate of Honour of His Holiness.[55]

Archbishop of Munich and Freising: 1977–1982

On 24 March 1977, Ratzinger was appointed Archbishop of Munich and Freising, and was ordained a bishop on 28 May. He took as his episcopal motto Cooperatores veritatis (Latin for 'cooperators of the truth'),[56] from the Third Epistle of John,[57] a choice on which he commented in his autobiographical work Milestones.[58]

In the consistory of 27 June 1977, he was named Cardinal Priest of Santa Maria Consolatrice al Tiburtino by Pope Paul VI. By the time of the 2005 conclave, he was one of only fourteen remaining cardinals appointed by Paul VI, and one of only three of those under the age of 80. Of these, only he and William Wakefield Baum took part in the conclave.[59]

Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith: 1981–2005

On 25 November 1981, Pope John Paul II, upon the retirement of Franjo Šeper, named Ratzinger as the Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, formerly known as the "Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office", the historical Roman Inquisition. Consequently, he resigned from his post in Munich in early 1982. He was promoted within the College of Cardinals to become Cardinal Bishop of Velletri-Segni in 1993 and was made the college's vice-dean in 1998 and dean in 2002. Just a year after its foundation in 1990, Ratzinger joined the European Academy of Sciences and Arts in Salzburg.[60][61]

Ratzinger defended and reaffirmed Catholic doctrine, including teaching on topics such as birth control, homosexuality, and inter-religious dialogue. The theologian Leonardo Boff, for example, was suspended, while others such as Matthew Fox were censured. Other issues also prompted condemnations or revocations of rights to teach: for instance, some posthumous writings of Jesuit priest Anthony de Mello were the subject of a notification. Ratzinger and the congregation viewed many of them, particularly the later works, as having an element of religious indifferentism (in other words, that Christ was "one master alongside others"). In particular, Dominus Iesus, published by the congregation in the jubilee year 2000, reaffirmed many recently "unpopular" ideas, including the Catholic Church's position that "salvation is found in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given to men by which we must be saved." The document angered many Protestant churches by claiming that they are not churches, but "ecclesial communities".[62]

Ratzinger's 2001 letter De delictis gravioribus clarified the confidentiality of internal church investigations, as defined in the 1962 document Crimen sollicitationis, into accusations made against priests of certain crimes, including sexual abuse. This became a subject of controversy during the sex abuse cases.[63] For 20 years, Ratzinger had been the man in charge of enforcing the document.[64]

While bishops hold the secrecy pertained only internally, and did not preclude investigation by civil law enforcement, the letter was often seen as promoting a coverup.[65] Later, as pope, he was accused in a lawsuit of conspiring to cover up the molestation of three boys in Texas, but sought and obtained diplomatic immunity from liability.[66]

On 12 March 1983, Ratzinger, as prefect, notified the lay faithful and the clergy that Archbishop Pierre Martin Ngô Đình Thục had incurred excommunication latae sententiae for illicit episcopal consecrations without the apostolic mandate. In 1997, when he turned 70, Ratzinger asked Pope John Paul II for permission to leave the Congregation of the Doctrine of Faith and to become an archivist in the Vatican Secret Archives and a librarian in the Vatican Library, but John Paul refused his assent.[67][68]

Ratzinger engaged in a dialogue with critical theorist Jürgen Habermas in 2004, published three years later by Ignatius Press.[69][non-primary source needed]

Papacy: 2005–2013

Election to the papacy

In April 2005, before his election as pope, Ratzinger was identified as one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time.[70] While Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Ratzinger repeatedly stated he would like to retire to his house in the Bavarian village of Pentling near Regensburg and dedicate himself to writing books.[71]

At the papal conclave, "it was, if not Ratzinger, who? And as they came to know him, the question became, why not Ratzinger?"[72][73] On 19 April 2005, he was elected on the second day after four ballots.[72] Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O'Connor described the final vote, "It's very solemn when you go up one by one to put your vote in the urn and you're looking up at the Last Judgement of Michelangelo. And I still remember vividly the then Cardinal Ratzinger sitting on the edge of his chair."[74] Ratzinger had hoped to retire peacefully and said that "At a certain point, I prayed to God 'please don't do this to me'...Evidently, this time He didn't listen to me."[75]

The day following Ratzinger's election, the German newspaper Bild ran what would become one of its most iconic headlines in response to the announcement of the prior day, Wir Sind Papst (We are Pope).[76]

At the balcony, Benedict's first words to the crowd, given in Italian before he gave the traditional Urbi et Orbi blessing in Latin, were:

Dear brothers and sisters, after the great Pope John Paul II, the Cardinals have elected me, a simple, humble labourer in the vineyard of the Lord. The fact that the Lord knows how to work and to act even with insufficient instruments comforts me, and above all I entrust myself to your prayers. In the joy of the Risen Lord, confident of his unfailing help, let us move forward. The Lord will help us, and Mary, His Most Holy Mother, will be on our side. Thank you.[77]

On 24 April, Benedict celebrated the Papal Inauguration Mass in St. Peter's Square, during which he was invested with the Pallium and the Ring of the Fisherman.[78] On 7 May, he took possession of his cathedral church, the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran.[79]

Choice of name

Benedict XVI chose his papal name, which comes from the Latin word meaning "the blessed", in honour of both Benedict XV and Benedict of Nursia.[80] Benedict XV was pope during the First World War, during which time he passionately pursued peace between the warring nations. St. Benedict of Nursia was the founder of the Benedictine monasteries (most monasteries of the Middle Ages were of the Benedictine order) and the author of the Rule of Saint Benedict, which is still the most influential writing regarding the monastic life of Western Christianity. The Pope explained his choice of name during his first general audience in St. Peter's Square, on 27 April 2005:

Filled with sentiments of awe and thanksgiving, I wish to speak of why I chose the name Benedict. Firstly, I remember Pope Benedict XV, that courageous prophet of peace, who guided the Church through turbulent times of war. In his footsteps, I place my ministry in the service of reconciliation and harmony between peoples. Additionally, I recall Saint Benedict of Nursia, co-patron of Europe, whose life evokes the Christian roots of Europe. I ask him to help us all to hold firm to the centrality of Christ in our Christian life: May Christ always take first place in our thoughts and actions![81]

Tone of papacy

During Benedict's inaugural Mass, the previous custom of every cardinal submitting to the pope was replaced by being greeted by twelve people, including cardinals, clergy, religious, a married couple and their child, and some who were newly confirmed people; the cardinals had formally sworn their obedience upon the election of the new pontiff. He began using an open-topped papal car, saying that he wanted to be closer to the people. Benedict continued the tradition of his predecessor John Paul II and baptised several infants in the Sistine Chapel at the beginning of each year, on the Feast of the Baptism of the Lord, in his pastoral role as Bishop of Rome.[82]

Beatifications

During his pontificate, Benedict XVI beatified 870 people. On 9 May 2005, Benedict XVI began the beatification process for his predecessor, Pope John Paul II. Normally, five years must pass after a person's death before the beatification process can begin. However, in an audience with Benedict, Camillo Ruini, vicar general of the Diocese of Rome and the official responsible for promoting the cause for canonization of any person who dies within that diocese, cited "exceptional circumstances" which suggested that the waiting period could be waived. (This had happened before, when Pope Paul VI waived the five-year rule and announced beatification processes for two of his own predecessors, Pope Pius XII and Pope John XXIII. Benedict XVI followed this precedent when he waived the five-year rule for John Paul II.[83]) The decision was announced on 13 May 2005, the Feast of Our Lady of Fátima and the 24th anniversary of the attempt on John Paul II's life.[84] John Paul II often credited Our Lady of Fátima for preserving him on that day. Cardinal Ruini inaugurated the diocesan phase of the cause for beatification in the Lateran Basilica on 28 June 2005.[85]

The first beatification under the new pope was celebrated on 14 May 2005, by José Cardinal Saraiva Martins, Cardinal Prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints. The new Blesseds were Marianne Cope and Ascensión Nicol Goñi. Cardinal Clemens August Graf von Galen was beatified on 9 October 2005. Mariano de la Mata was beatified in November 2006 and Rosa Eluvathingal was beatified on 3 December of that year, and Basil Moreau was beatified in September 2007.[86] In October 2008, the following beatifications took place: Celestine of the Mother of God, Giuseppina Nicoli, Hendrina Stenmanns, Maria Rosa Flesch, Marta Anna Wiecka, Michael Sopocko, Petrus Kibe Kasui and 187 Companions, Susana Paz-Castillo Ramírez, and Maria Isbael Salvat Romero.

On 19 September 2010, during his visit to the United Kingdom, Benedict personally proclaimed the beatification of John Henry Newman.[87]

Unlike his predecessor, Benedict delegated the beatification liturgical service to a cardinal. On 29 September 2005, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints issued a communiqué announcing that henceforth beatifications would be celebrated by a representative of the pope, usually the prefect of that Congregation.[88]

Canonizations

During his pontificate, Benedict XVI canonized 45 people.[89] He celebrated his first canonizations on 23 October 2005 in St. Peter's Square when he canonized Josef Bilczewski, Alberto Hurtado, Zygmunt Gorazdowski, Gaetano Catanoso, and Felice da Nicosia. The canonizations were part of a mass that marked the conclusion of the General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops and the Year of the Eucharist.[90] Benedict canonized Bishop Rafael Guízar y Valencia, Théodore Guérin, Filippo Smaldone, and Rosa Venerini on 15 October 2006.

During his visit to Brazil in 2007, Benedict presided over the canonization of Frei Galvão on 11 May, while George Preca, founder of the Malta-based MUSEUM, Szymon of Lipnica, Charles of Mount Argus, and Marie-Eugénie de Jésus were canonized in a ceremony held at the Vatican on 3 June 2007.[91] Preca is the first Maltese saint since the country's conversion to Christianity in A.D. 60 when St. Paul converted the inhabitants.[92] In October 2008, the following canonizations took place: Alphonsa of the Immaculate Conception of India,[93] Gaetano Errico, Narcisa de Jesus Martillo Moran, and Maria Bernarda Bütler. In April 2009, the Pope canonized Arcangelo Tadini, Bernardo Tolomei, Nuno Álvares Pereira, Geltrude Comensoli, and Caterina Volpicelli.[94] In October of the same year he canonized Jeanne Jugan, Damien de Veuster, Zygmunt Szczęsny Feliński, Francisco Coll Guitart, and Rafael Arnáiz Barón.[95][96]

On 17 October 2010, Benedict canonized André Bessette, a French-Canadian; Stanisław Sołtys, a 15th-century Polish priest; Italian nuns Giulia Salzano and Camilla Battista da Varano; Spanish nun Candida Maria de Jesus Cipitria y Barriola; and the first Australian saint, Mary MacKillop.[97] On 23 October 2011, he canonized three saints: a Spanish nun Bonifacia Rodríguez y Castro, Italian archbishop Guido Maria Conforti, and Italian priest Luigi Guanella.[98] In December 2011, the Pope formally recognized the validity of the miracles necessary to proceed with the canonizations of Kateri Tekakwitha, who would be the first Native American saint; Marianne Cope, a nun working with lepers in what is now the state of Hawaii; Giovanni Battista Piamarta, an Italian priest; Jacques Berthieu, a French Jesuit priest and African martyr; Carmen Salles y Barangueras, a Spanish nun and founder of the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception; Peter Calungsod, a lay catechist and martyr from the Philippines; and Anna Schäffer, whose desire to be a missionary was unfulfilled on account of her illness.[99] They were canonized on 21 October 2012.[100]

Doctors of the Church

On 7 October 2012, Benedict named Hildegard of Bingen and John of Ávila as Doctors of the Church, the 34th and 35th individuals so recognized in the history of Christianity.[101]

Curia reform

Benedict made only modest changes to the structure of the Roman Curia. In March 2006, he placed both the Pontifical Council for Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant Peoples and the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace under a single president, Cardinal Renato Martino. When Martino retired in 2009, each council received its own president once again. Also in March 2006, the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue was briefly merged into the Pontifical Council for Culture under Cardinal Paul Poupard. Those Councils maintained their separate officials and staffs while their status and competencies continued unchanged, and in May 2007, Interreligious Dialogue was restored to its separate status again with its own president.[102] In June 2010, Benedict created the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of the New Evangelization, appointing Archbishop Rino Fisichella its first president.[103] On 16 January 2013, the Pope transferred responsibility for catechesis from the Congregation for the Clergy to the Pontifical Council for Promoting the New Evangelization.[104]

Teachings

As pope, one of Benedict's main roles was to teach about the Catholic faith and the solutions to the problems of discerning and living the faith,[105] a role that he could play well as a former head of the Church's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

"Friendship with Jesus Christ"

After his first homily as pope, Benedict referred to both Jesus Christ and John Paul II. Citing John Paul II's well-known words, "Do not be afraid! Open wide the doors for Christ!", Benedict said:

Are we not perhaps all afraid in some way? If we let Christ enter fully into our lives, if we open ourselves totally to Him, are we not afraid that He might take something away from us? ... And once again the Pope said: No! If we let Christ into our lives, we lose nothing, nothing, absolutely nothing of what makes life free, beautiful, and great. No! Only in this friendship do we experience beauty and liberation. ... When we give ourselves to Him, we receive a hundredfold in return. Yes, open, open wide the doors to Christ – and you will find true life.[106]

"Friendship with Jesus Christ" was a frequent theme of Benedict's preaching.[107][108] He stressed that on this intimate friendship, "everything depends".[109] He also said: "We are all called to open ourselves to this friendship with God ... speaking to Him as to a friend, the only One who can make the world both good and happy ... That is all we have to do is put ourselves at His disposal ... is an extremely important message. It is a message that helps to overcome what can be considered the great temptation of our time: the claim, that after the Big Bang, God withdrew from history."[110] Thus, in his book Jesus of Nazareth, his main purpose was "to help foster [in the reader] the growth of a living relationship" with Jesus Christ.[109] He took up this theme in his first encyclical Deus caritas est. In his explanation and summary of the encyclical, he stated: "If friendship with God becomes for us something ever more important and decisive, then we will begin to love those whom God loves and who are in need of us. God wants us to be friends of His friends and we can be so, if we are interiorly close to them."[111] Thus, he said that prayer is "urgently needed ... It is time to reaffirm the importance of prayer in the face of the activism and the growing secularism of many Christians engaged in charitable work."[112]

"Dictatorship of relativism"

Continuing what he said in the pre-conclave Mass about what he often referred to as the "central problem of our faith today",[113] on 6 June 2005, Benedict also said:

Today, a particularly insidious obstacle to the task of education is the massive presence in our society and culture of that relativism which, recognising nothing as definitive, leaves as the ultimate criterion only the self with its desires. And under the semblance of freedom it becomes a prison for each one, for it separates people from one another, locking each person into his or her own ego.[114]

Benedict said that "a dictatorship of relativism"[115] was the core challenge facing the Church and humanity. At the root of this problem, he said, is Immanuel Kant's "self-limitation of reason". This, he said, is contradictory to the modern acclamation of science whose excellence is based on the power of reason to know the truth. He said that this self-amputation of reason leads to pathologies of religion such as terrorism and pathologies of science such as ecological disasters.[116] Benedict traced the failed revolutions and violent ideologies of the 20th century to a conversion of partial points of view into absolute guides. He said "Absolutizing what is not absolute but relative is called totalitarianism."[117]

Christianity as religion according to reason

In the discussion with secularism and rationalism, one of Benedict's basic ideas can be found in his address on the "Crisis of Culture" in the West, a day before Pope John Paul II died, when he referred to Christianity as the "religion of the Logos" (the Greek for "word", "reason", "meaning", or "intelligence"). He said:

From the beginning, Christianity has understood itself as the religion of the Logos, as the religion according to reason ... It has always defined men, all men without distinction, as creatures and images of God, proclaiming for them ... the same dignity. In this connection, the Enlightenment is of Christian origin and it is no accident that it was born precisely and exclusively in the realm of the Christian faith. ... It was and is the merit of the Enlightenment to have again proposed these original values of Christianity and of having given back to reason its own voice ... Today, this should be precisely [Christianity's] philosophical strength, in so far as the problem is whether the world comes from the irrational, and reason is not other than a 'sub-product,' on occasion even harmful of its development – or whether the world comes from reason, and is, as a consequence, its criterion and goal ... In the so necessary dialogue between secularists and Catholics, we Christians must be very careful to remain faithful to this fundamental line: to live a faith that comes from the Logos, from creative reason, and that, because of this, is also open to all that is truly rational.[118]

Benedict also emphasised that "Only creative reason, which in the crucified God is manifested as love, can really show us the way."[118]

Encyclicals

Benedict wrote three encyclicals: Deus caritas est (Latin for "God is Love"), Spe salvi ("Saved by Hope"), and Caritas in veritate ("Love in Truth").

In his first encyclical, Deus caritas est, he said that a human being, created in the image of God who is love, can practise love: to give himself to God and others (agape) by receiving and experiencing God's love in contemplation. This life of love, according to him, is the life of the saints such as Teresa of Calcutta and the Blessed Virgin Mary, and is the direction Christians take when they believe that God loves them in Jesus Christ.[119] The encyclical contains almost 16,000 words in 42 paragraphs. The first half is said to have been written by Benedict in German, his first language, in the summer of 2005; the second half is derived from uncompleted writings left by his predecessor, Pope John Paul II.[120] The document was signed by Benedict on Christmas Day, 25 December 2005.[121] The encyclical was promulgated a month later in Latin and was translated into English, French, German, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, and Spanish. It is the first encyclical to be published since the Vatican decided to assert copyright in the official writings of the pope.[122]

Benedict's second encyclical titled Spe Salvi ("Saved by Hope"), about the virtue of hope, was released on 30 November 2007.[123][124]

His third encyclical titled Caritas in veritate ("Love in Truth" or "Charity in Truth"), was signed on 29 June 2009 (the Feast of Sts. Peter and Paul) and released on 7 July 2009.[125] In it, the Pope continued the Church's teachings on social justice. He condemned the prevalent economic system "where the pernicious effects of sin are evident," and called on people to rediscover ethics in business and economic relations.[125]

At the time of his resignation, Benedict had completed a draft of a fourth encyclical entitled Lumen fidei ("The Light of Faith"),[126] intended to accompany his first two encyclicals to complete a trilogy on the three theological virtues of faith, hope, and love. Benedict's successor, Francis, completed and published Lumen Fidei in June 2013, four months after Benedict's retirement and Francis's succession. Although the encyclical is officially the work of Francis, paragraph 7 of the encyclical explicitly expresses Francis's debt to Benedict: "These considerations on faith – in continuity with all that the Church's magisterium has pronounced on this theological virtue – are meant to supplement what Benedict XVI had written in his encyclical letters on charity and hope. He himself had almost completed a first draft of an encyclical on faith. For this I am deeply grateful to him, and as his brother in Christ I have taken up his fine work and added a few contributions of my own."[127]

Post-synodal apostolic exhortation

Sacramentum caritatis (The Sacrament of Charity), signed 22 February 2007, was released in Latin, Italian, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish, and Polish. It was made available in various languages on 13 March 2007 in Rome. The English edition of Libera Editrice Vaticana is 158 pages. This apostolic exhortation "seeks to take up the richness and variety of the reflections and proposals which emerged from the Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops" which was held in 2006.[128]

Motu proprio on Tridentine Mass

On 7 July 2007, Benedict issued the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum, declaring that upon "the request of the faithful", the celebration of Mass according to the Missal of 1962 (of the Tridentine Mass), was to be more easily permitted. Stable groups who previously had to petition their bishop to have a Tridentine Mass may now merely request permission from their local priest.[129] While Summorum Pontificum directs that pastors should provide the Tridentine Mass upon the requests of the faithful, it also allows for any qualified priest to offer private celebrations of the Tridentine Mass, to which the faithful may be admitted if they wish.[130] For regularly scheduled public celebrations of the Tridentine Mass, the permission of the priest in charge of the church is required.[131]

In an accompanying letter, the Pope outlined his position concerning questions about the new guidelines.[130] As there were fears that the move would entail a reversal of the Second Vatican Council,[132] Benedict emphasised that the Tridentine Mass would not detract from the council and that the Mass of Paul VI would still be the norm and priests were not permitted to refuse to say the Mass in that form. He pointed out that the use of Tridentine Mass "was never juridically abrogated and, consequently, in principle, was always permitted."[130] The letter also decried "deformations of the liturgy ... because in many places celebrations were not faithful to the prescriptions of the new Missal" as the Second Vatican Council was wrongly seen "as authorising or even requiring creativity", mentioning his own experience.[130]

The Pope considered that allowing the Tridentine Mass to those who request it was a means to prevent or heal schism, stating that, on occasions in history, "not enough was done by the Church's leaders to maintain or regain reconciliation and unity" and that this "imposes an obligation on us today: to make every effort to enable for all those who truly desire unity to remain in that unity or to attain it anew."[130] Cardinal Darío Castrillón Hoyos, the president of the Pontifical Commission established to facilitate full ecclesial communion of those associated with that Society,[133] stated that the decree "opened the door for their return". Bishop Bernard Fellay, superior general of the SSPX, expressed "deep gratitude to the Sovereign Pontiff for this great spiritual benefit".[129]

In July 2021, Pope Francis issued the apostolic letter titled Traditionis custodes, which substantially reversed the decision of Benedict XVI in Summorum Pontificum and imposed new and broad restrictions on the use of the Traditional Latin Mass. The decision was controversial and widely criticized by conservative and traditionalist Catholics as lacking in charity and an attack on those attached to the liturgical patrimony of the Church.[134][135]

Unicity and salvific universality of the Catholic Church

Near the end of June 2007, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith issued a document approved by Benedict XVI "because some contemporary theological interpretations of Vatican II's ecumenical intent had been 'erroneous or ambiguous' and had prompted confusion and doubt." The document has been seen as restating "key sections of a 2000 text the pope wrote when he was prefect of the congregation, Dominus Iesus."[136]

Consumerism

Benedict condemned excessive consumerism, especially among youth. He stated in December 2007 that "[A]dolescents, youths and even children are easy victims of the corruption of love, deceived by unscrupulous adults who, lying to themselves and to them, draw them into the dead-end streets of consumerism."[137] In June 2009, he blamed outsourcing for the greater availability of consumer goods which lead to the downsizing of social security systems.[138]

Ecumenism

Speaking at his weekly audience in St. Peter's Square on 7 June 2006, Benedict asserted that Jesus himself had entrusted the leadership of the Church to his apostle Peter. "Peter's responsibility thus consists of guaranteeing the communion with Christ. Let us pray so that the primacy of Peter, entrusted to poor human beings, may always be exercised in this original sense desired by the Lord, so that it will be increasingly recognised in its true meaning by brothers who are still not in communion with us."[139]

Also in 2006, Benedict met the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams. In their Common Declaration, they highlighted the previous 40 years of dialogue between Catholics and Anglicans while also acknowledging "serious obstacles to our ecumenical progress".[140]

On 4 November 2009, in response to a 2007 petition by the Traditional Anglican Church, Benedict issued the apostolic constitution Anglicanorum coetibus, which authorized the creation of "Personal Ordinariates for Anglicans entering into full communion."[141][142] Between 2011 and 2012, three ordinariates were erected, currently totalling 9090 members, 194 priests, and 94 parishes.[143][144][145]

Interfaith dialogue

Judaism

When Benedict ascended to the papacy, his election was welcomed by the Anti-Defamation League who noted "his great sensitivity to Jewish history and the Holocaust".[146] However, his election received a more reserved response from British Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, who hoped that Benedict would "continue along the path of Pope John XXIII and Pope John Paul II in working to enhance relations with the Jewish people and the State of Israel."[147] Israeli foreign minister Silvan Shalom also offered tentative praise, though Shalom believed that "this Pope, considering his historical experience, will be especially committed to an uncompromising fight against anti-Semitism."[147]

Critics have accused Benedict's papacy of insensitivity towards Judaism. The two most prominent instances were the expansion of the use of the Tridentine Mass and the lifting of the excommunication on four bishops from the Society of St. Pius X (SSPX). In the Good Friday service, the Tridentine Mass rubrics include a prayer that asks God to lift the veil so they [Jews] may be delivered from their darkness. This prayer has historically been contentious in Judaic-Catholic relations and several groups saw the restoration of the Tridentine Mass as problematic.[148][149][150][151][152] Among those whose excommunications were lifted was Bishop Richard Williamson, an outspoken historical revisionist sometimes interpreted as a Holocaust denier.[153][154][155][156] The lifting of his excommunication led critics to charge that the Pope was condoning his historical revisionist views.[157]

Islam

Benedict's relations with Islam were strained at times. On 12 September 2006, he delivered a lecture which touched on Islam at the University of Regensburg in Germany. He had served there as a professor of theology before becoming Pope, and his lecture was entitled "Faith, Reason and the University – Memories and Reflections". The lecture received much attention from political and religious authorities. Many Islamic politicians and religious leaders registered their protest against what they labelled an insulting mischaracterization of Islam, although his focus was aimed towards the rationality of religious violence, and its effect on the religion.[158][159] Muslims were particularly offended by a passage that the Pope quoted in his speech: "Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached."[159]

The passage originally appeared in the Dialogue Held with a Certain Persian, the Worthy Mouterizes, in Anakara of Galatia[160] written in 1391 as an expression of the views of the Byzantine emperor Manuel II Palaeologus, one of the last Christian rulers before the Fall of Constantinople to the Muslim Ottoman Empire, on such issues as forced conversion, holy war, and the relationship between faith and reason. According to the German text, the Pope's original comment was that the emperor "addresses his interlocutor in an astoundingly harsh – to us surprisingly harsh – way" (wendet er sich in erstaunlich schroffer, uns überraschend schroffer Form).[161] Benedict apologized for any offence he had caused and made a point of visiting Turkey, a predominantly Muslim country, and praying in its Blue Mosque. Benedict planned on 5 March 2008, to meet with Muslim scholars and religious leaders autumn 2008 at a Catholic-Muslim seminar in Rome.[162] That meeting, the "First Meeting of the Catholic-Muslim Forum," was held from 4–6 November 2008.[163] On 9 May 2009, Benedict visited the King Hussein Mosque in Amman, Jordan where he was addressed by Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad.[164]

Buddhism

The Dalai Lama congratulated Benedict XVI upon his election,[165] and visited him in October 2006 in Vatican City. In 2007, the People's Republic of China was accused of using its political influence to stop a meeting between the Pope and the Dalai Lama.[166]

Indigenous American beliefs

While visiting Brazil in May 2007, "the pope sparked controversy by saying that native populations had been 'silently longing' for the Christian faith brought to South America by colonizers."[167] The Pope continued, stating that "the proclamation of Jesus and of his Gospel did not at any point involve an alienation of the pre-Columbus cultures, nor was it the imposition of a foreign culture."[167] Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez demanded an apology, and an indigenous organization in Ecuador issued a response which stated that "representatives of the Catholic Church of those times, with honourable exceptions, were accomplices, deceivers and beneficiaries of one of the most horrific genocides of all humanity."[167] Later, the Pope, speaking Italian, said at a weekly audience that it was "not possible to forget the suffering and the injustices inflicted by colonizers against the indigenous population, whose fundamental human rights were often trampled" but made no apology.[168]

Hinduism

While visiting the United States on 17 April 2008, Benedict met with International Society for Krishna Consciousness representative Radhika Ramana Dasa,[169] a noted Hindu scholar[170] and disciple of Hanumatpreshaka Swami.[171] On behalf of the Hindu American community, Radhika Ramana Dasa presented a gift of an Om symbol to Benedict.[172][173]

Pastoral visits and security

As pontiff, Benedict carried out numerous Apostolic activities, including journeys in Italy and across the world.

Benedict travelled extensively during the first three years of his papacy. In addition to his travels within Italy, he made two visits to his homeland, Germany, one for World Youth Day and another to visit the towns of his childhood. He also visited Poland and Spain, where he was enthusiastically received.[174] His visit to Turkey, an overwhelmingly Muslim nation, was initially overshadowed by the controversy about a lecture he had given at Regensburg. His visit was met by nationalist and Islamic protesters[175] and was placed under unprecedented security measures.[176] Benedict made a joint declaration with Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I in an attempt to begin to heal the rift between the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches.[177]

In 2007, Benedict visited Brazil to address the Bishops' Conference there and canonize Friar Antônio Galvão, an 18th-century Franciscan. In June 2007, Benedict made a personal pilgrimage and pastoral visit to Assisi, the birthplace of St. Francis. In September, Benedict undertook a three-day visit to Austria,[178] during which he joined Vienna's chief rabbi, Paul Chaim Eisenberg, in a memorial to the 65,000 Viennese Jews who perished in Nazi death camps.[179] During his stay in Austria, he also celebrated Mass at the Marian shrine Mariazell and visited Heiligenkreuz Abbey.[180]

In April 2008, Benedict made his first visit to the United States since becoming pope.[181] He arrived in Washington, D.C., where he was formally received at the White House and met privately with US president George W. Bush.[182] While in Washington, the pope addressed representatives of US Catholic universities, met with leaders of other world religions, and celebrated Mass at the Washington Nationals' baseball stadium with 47,000 people.[183] The Pope also met privately with victims of sexual abuse by priests. The Pope travelled to New York City where he addressed the United Nations General Assembly.[184] Also while in New York, the Pope celebrated Mass at St. Patrick's Cathedral, met with disabled children and their families, and attended an event for Catholic youth, where he addressed some 25,000 young people in attendance.[185] On the final day of the Pope's visit, he visited the World Trade Center site and later celebrated Mass at Yankee Stadium.[186]

In July 2008, the Pope travelled to Australia to attend World Youth Day 2008 in Sydney. On 19 July, in St. Mary's Cathedral, he made an apology for child sex abuse perpetrated by the clergy in Australia.[187][188] On 13 September 2008, at an outdoor Paris Mass attended by 250,000 people, Benedict condemned the modern materialism – the world's love of power, possessions, and money as a modern-day plague, comparing it to paganism.[189][190] In 2009, he visited Africa (Cameroon and Angola) for the first time as pope. During his visit, he suggested that altering sexual behaviour was the answer to Africa's AIDS crisis and urged Catholics to reach out and convert believers in sorcery.[191] He visited the Middle East (Jordan, Israel, and Palestine) in May 2009.

Benedict's main arena for pastoral activity was the Vatican itself, his Christmas and Easter homilies and Urbi et Orbi were delivered from St. Peter's Basilica. The Vatican is also the only regular place where Benedict travelled via motor without the protective bulletproof case common to most popemobiles. Despite the more secure setting, Benedict was victim to security risks several times inside Vatican City. On Wednesday, 6 June 2007, during his General Audience, a man leapt across a barrier, evaded guards, and nearly mounted the Pope's vehicle, although he was stopped and Benedict seemed to be unaware of the event. On Thursday, 24 December 2009, while Benedict was proceeding to the altar to celebrate Christmas Eve Mass at St. Peter's Basilica, a woman later identified as 25-year-old Susanna Maiolo, who holds Italian and Swiss citizenship, jumped the barrier and grabbed the Pope by his vestments and pulled him to the ground. The 82-year-old Benedict fell but was assisted to his feet and he continued to proceed toward the altar to celebrate Mass. Roger Etchegaray, the vice-dean of the College of Cardinals, fell as well and suffered a hip fracture. Italian police reported that Maiolo had in a prior action attempted to accost Benedict at the previous Christmas Eve Mass, but was prevented from doing so.[192][193]

In his homily, Benedict forgave Susanna Maiolo[194] and urged the world to "wake up" from selfishness and petty affairs, and find time for God and spiritual matters.[192]

Between 17 and 18 April 2010, Benedict made an Apostolic Journey to the Republic of Malta. Following meetings with various dignitaries on his first day on the island, 50,000 people gathered in a drizzle for Papal Mass on the granaries in Floriana. The Pope also met with the Maltese youth at the Valletta Waterfront, where an estimated 10,000 young people turned up to greet him.[195]

Sexual abuse in the Catholic Church

Prior to 2001, the primary responsibility for investigating allegations of sexual abuse and disciplining perpetrators rested with the individual dioceses. In 2001, Ratzinger convinced John Paul II to put the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in charge of all sexual abuse investigations.[196][197] According to John L. Allen Jr., Ratzinger in the following years "acquired a familiarity with the contours of the problem that virtually no other figure in the Catholic Church can claim. Driven by that encounter with what he would later refer to as 'filth' in the Church, Ratzinger seems to have undergone something of a 'conversion experience' throughout 2003–04. From that point forward, he and his staff seemed driven by a convert's zeal to clean up the mess."[198]

Cardinal Vincent Nichols wrote that in his role as head of the CDF "[Ratzinger] led important changes made in church law: the inclusion in canon law of internet offences against children, the extension of child abuse offences to include the sexual abuse of all under 18, the case by case waiving of the statute of limitation and the establishment of a fast-track dismissal from the clerical state for offenders."[199] According to Charles J. Scicluna, a former prosecutor handling sexual abuse cases, "Cardinal Ratzinger displayed great wisdom and firmness in handling those cases, also demonstrating great courage in facing some of the most difficult and thorny cases, sine acceptione personarum [without respect of persons]".[200] According to Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, Ratzinger "made entirely clear efforts not to cover things up but to tackle and investigate them. This was not always met with approval in the Vatican".[196][201] Ratzinger had pressed John Paul II to investigate Hans Hermann Groër, an Austrian cardinal and friend of John Paul accused of sexual abuse, which resulted in Groër's resignation.[202]

In March 2010, Benedict sent a pastoral letter to the Catholic Church in Ireland addressing cases of sexual abuse by priests of minors, expressing sorrow and promising changes in the way in which accusations of abuse were addressed.[203] Victims' groups claimed the letter failed to clarify if secular law enforcement had priority over canon law confidentiality regarding internal investigation of abuse allegations.[204][205][206] The Pope then promised to introduce measures that would "safeguard young people in the future" and "bring to justice" priests who were responsible for abuse and the next month the Vatican issued guidelines on how existing church law should be implemented. The guidelines asserted that "Civil law concerning reporting of crimes ... should always be followed."[207][208]

As Archbishop of Munich and Freising

Despite being more proactive than his predecessor in addressing sexual abuse, Benedict was nonetheless cited as failing to do so on more than one occasion. In January 2022, a report written by German law firm Westpfahl Spilker Wastl and commissioned by the Catholic Church concluded that Cardinal Ratzinger failed to adequately take action against clerics in four cases of alleged abuse while he was Archbishop of Munich and Freising from 1977 to 1982. The pope emeritus denied the accusations.[209][210][211] Benedict corrected his former statement that he had not been at a meeting of the ordinariate of the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising in January 1980, saying he mistakenly told German investigators he was not there. However, the error was "not done out of bad faith", but "the result of an error in the editorial processing" of his statement. According to Reuters, lawyer Martin Pusch said that "in a total of four cases, we have come to the conclusion that the then Archbishop Cardinal Ratzinger can be accused of misconduct in cases of sexual abuse."[212][213]

In February 2022, Benedict admitted that errors were made in the treating of sexual abuse cases when he was Archbishop of Munich. According to the letter released by the Vatican, he asked forgiveness for any "grievous fault" but denied personal wrongdoing. Benedict stated: "I have had great responsibilities in the Catholic Church. All the greater is my pain for the abuses and the errors that occurred in those different places during the time of my mandate."[214] Public prosecutor's office in Munich had begun investigations as a result of the 2022 report against both Benedict and Cardinal Friedrich Wetter. The investigation was "discontinued" in March 2023 after it "did not reveal sufficient suspicion of criminal activity". The case of the investigation "was not acts of abuse committed by the Church personnel managers themselves, but possible acts of aiding and abetting by active action or omission".[215]

Legion of Christ founder Marcial Maciel

One of the cases Ratzinger pursued involved Marcial Maciel, a Mexican priest and founder of the Legionaries of Christ who had been accused repeatedly of sexual abuse. Biographer Andrea Tornielli suggested that Cardinal Ratzinger had wanted to take action against Maciel but that John Paul II and other high-ranking officials, including several cardinals and the Pope's influential secretary Stanisław Dziwisz, prevented him from doing so.[197][202]

According to Jason Berry, Cardinal Angelo Sodano "pressured" Ratzinger, who was "operating on the assumption that the charges were not justified", to halt the proceedings against Maciel in 1999.[216] When Maciel was honoured by the Pope in 2004, new accusers came forward[216] and Cardinal Ratzinger "took it on himself to authorize an investigation of Maciel".[197] After Ratzinger became pope, he began proceedings against Maciel and the Legion of Christ that forced Maciel out of active service in the Church.[196] On 1 May 2010, the Vatican issued a statement denouncing "the most serious and objectively immoral behaviour of Father Maciel, confirmed by incontrovertible witnesses, which amount to true crimes and show a life deprived of scruples and authentic religious feeling."[217]

Theodore McCarrick controversy

In November 2020, the Vatican published a report blaming Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI for allowing defrocked former cardinal Theodore McCarrick to rise in power despite the fact that they both knew of sex abuse allegations against him.[218][219] Despite the fact that Benedict pressured McCarrick to resign as Archbishop of Washington D.C. in 2006, McCarrick remained very active in ministry throughout Benedict's papacy and even made a very public appearance when he presided over US senator Ted Kennedy's burial service at Arlington National Cemetery in 2009.[218][219][220]

Post-papacy

In 2019, Benedict released a 6,000-word letter that attributed the Church's sexual abuse crisis to an erosion of morality driven by secularization and the sexual revolution of the 1960s.[221] The letter was in sharp contrast to the viewpoint of his successor, Francis, who saw the issue as a byproduct of abuses of power within the Church's hierarchical structure.[221] The New York Times later reported that "given his frail health at the time, however, many church watchers questioned whether Benedict had indeed written the letter or had been manipulated to issue it as a way to undercut Francis."[222]

Upon Benedict's death, his efforts to combat sexual abuse in the Church were remembered with mixed reactions, in particular by victims' groups. Francesco Zanardi, founder of the Italian victims' group Rete l'Abuso stated that "Ratzinger was less communicative than Francis but he moved" in the right direction, and that he was the first pontiff to effectively do so.[223] Anne Barrett Doyle, a co-director of BishopAccountability.org, an advocacy and research group, said that Benedict would be "remembered chiefly for his failure to achieve what should have been his job one: to rectify the incalculable harm done to the hundreds of thousands of children sexually abused by Catholic priests."[223] She stated that his tenure had "left hundreds of culpable bishops in power and a culture of secrecy intact," while the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests said in a statement that "Benedict was more concerned about the church's deteriorating image and financial flow to the hierarchy versus grasping the concept of true apologies followed by true amends to victims of abuse".[223]

Attire

Benedict re-introduced several papal garments which had fallen into disuse. He resumed the use of the traditional red papal shoes, which had been used since Roman times by popes but which had fallen into disuse during the pontificate of John Paul II. Contrary to the initial speculation of the press that the shoes had been made by the Italian fashion house Prada, the Vatican announced that the shoes were provided by the Pope's personal shoemaker.[224]

The journalist Charlotte Allen described Benedict as "the pope of aesthetics": "He has reminded a world that looks increasingly ugly and debased that there is such a thing as the beautiful – whether it's embodied in a sonata or an altarpiece or an embroidered cope or the cut of a cassock – and that earthly beauty ultimately communicates a beauty that is beyond earthly things."[16]

Health

Prior to his election as pope in 2005, Ratzinger had hoped to retire – on account of age-related health problems, a long-held desire to have free time to write, and the retirement age for bishops (75) – and submitted his resignation as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith three times, but continued at his post in obedience to the wishes of John Paul II. In September 1991, Ratzinger suffered a haemorrhagic stroke, which slightly impaired his eyesight temporarily but from which he recovered completely.[225] This was never officially made public – the official news was that he had fallen and struck his head against a radiator – but was an open secret known to the conclave that elected him pope.[226]

Following his election in April 2005 there were several rumours about the Pope's health, but none of them were confirmed. Early in his pontificate Benedict predicted a short reign, which led to concerns about his health.[227] In May 2005 the Vatican announced that he had suffered another mild stroke. French cardinal Philippe Barbarin said that since the first stroke Ratzinger had been suffering from an age-related heart condition, for which he was on medication. In late November 2006 Vatican insiders told the international press that the Pope had had a routine examination of the heart.[226] A few days later an unconfirmed rumour emerged that Benedict had undergone an operation in preparation for an eventual bypass operation, but this rumour was only published by a small left-wing Italian newspaper and was never confirmed by any Vatican insider.[228]

On 17 July 2009, Benedict was hospitalized after falling and breaking his right wrist while on vacation in the Alps; his injuries were reported to be minor.[229]

Following the announcement of his resignation, the Vatican revealed that Benedict had been fitted with a pacemaker while he was still a cardinal, before his election as pope in 2005. The battery in the pacemaker had been replaced three months earlier, a routine procedure, but that did not influence his decision.[230]

Resignation

On 11 February 2013, the Vatican confirmed that Benedict would resign the papacy on 28 February 2013, as a result of his advanced age,[231] becoming the first pope to resign since Gregory XII in 1415.[232] At the age of 85 years and 318 days on the effective date of his retirement, he was the fourth-oldest person to hold the office of pope. The move was unexpected,[233] as all popes in modern times had held office until death. Benedict was the first pope to resign without external pressure since Celestine V in 1294.[234][235]

In his declaration of 10 February 2013, Benedict resigned as "Bishop of Rome, Successor of Saint Peter".[236] In a statement, he cited his deteriorating strength and the physical and mental demands of the papacy;[237] addressing his cardinals in Latin, he gave a brief statement announcing his resignation. He also declared that he would continue to serve the Church "through a life dedicated to prayer".[237]

According to a statement from the Vatican, the timing of the resignation was not caused by any specific illness but was to "avoid that exhausting rush of Easter engagements".[238] After two weeks of ceremonial farewells, the Pope left office at the appointed time and sede vacante was declared. Benedict was succeeded by Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, who took the papal name of Francis on 13 March 2013.

On the eve of the first anniversary of Benedict's resignation he wrote to La Stampa to deny speculation he had been forced to step down. "There isn't the slightest doubt about the validity of my resignation from the Petrine ministry," he wrote in a letter to the newspaper. "The only condition for the validity is the full freedom of the decision. Speculation about its invalidity is simply absurd," he wrote.[239] In an interview on 28 February 2021, Benedict again repeated the legitimacy of his resignation.[240][241][242]

Pope emeritus: 2013–2022

On the morning of 28 February 2013, Benedict met with the full College of Cardinals and in the early afternoon flew by helicopter to the papal summer residence of Castel Gandolfo. He stayed there until refurbishment was completed on his retirement home, the Mater Ecclesiae Monastery in the Vatican Gardens near St. Peter's, former home of twelve nuns, where he moved on 2 May 2013.[243][244]

After his resignation, Benedict retained his papal name rather than reverting to his birth name.[9] He continued to wear the white cassock but without the pellegrina or the fascia. He ceased wearing red papal shoes.[245][246] Benedict returned his official Fisherman's Ring, which was rendered unusable by two large cuts across its face.[247]

According to a Vatican spokesman, Benedict spent his first day as Pope emeritus with Archbishop Georg Gänswein, Prefect of the Papal Household.[248] In the monastery, the pope emeritus did not live a cloistered life, but studied and wrote.[244] He joined Pope Francis several months later at the unveiling of a new statue of Saint Michael the Archangel. The inscription on the statue, according to Cardinal Giovanni Lajolo, has the coat of arms of the two popes to symbolize the fact that the statue was commissioned by Benedict and consecrated by Francis.[249]

In 2013 it was reported that Benedict had multiple health problems including high blood pressure and had fallen out of bed more than once, but the Holy See denied any specific illnesses.[250] The former pope made his first public appearance after his resignation at St. Peter's Basilica on 22 February 2014 to attend the first papal consistory of his successor Francis. Benedict entered the basilica through a discreet entrance and was seated in a row with several other cardinals. He doffed his zucchetto when Francis came down the nave of St. Peter's Basilica to greet him.[251] He then made an appearance at the canonization mass of Popes John XXIII and John Paul II, greeting the cardinals and Francis.

In August 2014, Benedict celebrated Mass at the Vatican and met with his former doctoral students, an annual tradition he had kept since the 1970s.[252] He attended the beatification of Pope Paul VI in October 2014.[253] Weeks before this, he joined Francis in Saint Peter's Square for an audience with grandparents to honour their importance in society.[254]

Benedict wrote the text of a speech, delivered by Archbishop Georg Gänswein, on the occasion of the dedication of the Aula Magna at the Pontifical Urbaniana University to the pope emeritus, "a gesture of gratitude for what he has done for the Church as a conciliar expert, with his teaching as professor, as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and, finally, the Magisterium." The ceremony took place on Tuesday, 21 October 2014, during the opening of the academic year.[255]

Benedict attended the consistory for new cardinals in February 2015, greeting Francis at the beginning of the celebration.[256] In the summer of 2015, Benedict spent two weeks at Castel Gandolfo, at the invitation of Pope Francis. While at Castel Gandolfo, Benedict participated in two public events. He received two honorary doctorates given to him by Cardinal Stanislaw Dziwisz, Pope John Paul II's longtime aide, from the Pontifical University of John Paul II and the Kraków Academy of Music.[257] In his reception address, Benedict paid homage to his predecessor, John Paul II.[257]

The Joseph Ratzinger–Benedict XVI Roman Library at the Pontifical Teutonic College was announced in April 2015 and was scheduled to open to scholars in November 2015.[258] The library section dedicated to his life and thought is being catalogued. It includes books by or about him and his studies, many donated by Benedict himself.[259][260]

Benedict, in August 2015, submitted a handwritten card to act as a testimony to the cause of canonization of Pope John Paul I.[261][262]

In March 2016, Benedict gave an interview expressing his views on mercy and endorsing Francis's stress on mercy in his pastoral practice.[263] Also that month, a Vatican spokesman stated that Benedict was "slowly, serenely fading" in his physical health, although his mental capacity remained "perfectly lucid".[264]

The pope emeritus was honoured by the Roman Curia and Francis in 2016 at a special audience, honouring the 65th anniversary of his ordination to the priesthood. That November, he did not attend the consistory for new cardinals, rather meeting with them and Francis at his residence afterward.[265] Following the death of Cardinal Paulo Evaristo Arns in December 2016, Benedict became the last living person appointed cardinal by Pope Paul VI.[266]

In June 2017, Benedict received newly created cardinals in his chapel and spoke with each of them in their native language.[267] In July 2017, he sent a message through his private secretary for the funeral of Cardinal Joachim Meisner, who had suddenly died while on vacation in Germany.[268]

In November 2017, images emerged on the Facebook page of the Bishop of Passau, Stefan Oster, of Benedict with a black eye; the bishop and author Peter Seewald visited the former pope on 26 October since the pair were presenting Benedict with the new book Benedict XVI – The German Pope which the Passau diocese created. The former pope suffered the hematoma earlier after having slipped.[269]

In late 2019, Benedict collaborated on a book expressing that the Catholic Church must maintain its discipline of clerical celibacy, in light of ongoing debate on the issue, though later requested his name to be removed from the book as co-author.[270][271][272]

In June 2020, Benedict visited his dying brother Georg in Germany for the last time.[273][274] Georg died on 1 July, aged 96.[275]

On 3 August 2020, Benedict's aides disclosed that he had an inflammation of the trigeminal nerve.[276] On 2 December of the same year, Maltese cardinal Mario Grech announced to Vatican News that Benedict had difficulty speaking and that he had told the new cardinals after the consistory that "the Lord has taken away my speech in order to let me appreciate silence".[277]

Benedict became the longest-lived pope, whose age can be verified, on 4 September 2020 at 93 years, 141 days, surpassing the age of Pope Leo XIII.[278][279] There are two popes that are claimed to have lived longer than Benedict: Pope St Agatho (574–681), who died at the age of 107;[280] and Pope Gregory IX (1145–1241), who died at the age of 96.[281] However, although there is some contemporary documentation attesting to their ages, there is not sufficient evidence for them to be verified with complete certainty.

In January 2021, Benedict and Francis each received doses of a COVID-19 vaccine.[282] On 29 June 2021, the pope emeritus celebrated his platinum jubilee (70th anniversary) as a priest.[283]

Following the consistory of 27 August 2022, Francis and the newly created cardinals paid a brief visit to Benedict at Mater Ecclesiae Monastery.[284]

Death and funeral

Worsening health and death

On 28 December 2022, Pope Francis said at the end of his audience that Benedict was "very sick" and asked God to "comfort him and support him in this testimony of love for the Church until the end".[285] The same day, Matteo Bruni, the director of the Holy See Press Office, stated that "in the last few hours there has been an aggravation of Benedict's health due to advancing age" and that he was under medical care. Bruni also stated that Francis visited Benedict at the Mater Ecclesiae Monastery after the audience.[286][287]

Benedict died on 31 December 2022 at 9:34 am Central European Time at the Mater Ecclesiae Monastery. He was 95 years old. His long-time secretary, Georg Gänswein, reported that his last words were "Signore ti amo" (Italian for 'Lord, I love you').[288][289][290]

Funeral

From 2 to 4 January 2023, Benedict's body lay in state in St. Peter's Basilica, during which around 195,000 people paid their respects.[291] His funeral took place on 5 January 2023 in St. Peter's Square at 9:30 am, presided over by Pope Francis and celebrated by Cardinal Giovanni Battista Re.[292] This was the first time since 1802 that a pope had attended a funeral for his predecessor.[293] The funeral was attended by an estimated 50,000 people.[294] Some attendees held signs reading or shouted "Santo subito", calling for his elevation to sainthood, a cry heard previously at the funeral of John Paul II.[295] Benedict was interred in the crypt beneath St. Peter's Basilica, in the same tomb originally occupied by John Paul II and John XXIII.[294] The tomb was opened to the public on 8 January 2023.[296]

Titles and styles

As Pope, Benedict's rarely used full title was:

His Holiness Benedict XVI, Bishop of Rome, Vicar of Jesus Christ, Successor of the Prince of the Apostles, Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church, Primate of Italy, Archbishop and Metropolitan of the Roman Province, Sovereign of the Vatican City State, Servant of the servants of God.[297]

The best-known title, that of "Pope", did not appear in the official list of titles, but is commonly used in the titles of documents, and appears, in abbreviated form, in their signatures as "PP." standing for "Papa" ("Pope").[298][299][300][301]

Before 1 March 2006, the list of titles also used to contain that of a "Patriarch of the West", which traditionally appeared in that list of titles before "Primate of Italy". The title of "Patriarch of the West" was removed in the 2006 edition of Annuario Pontificio. According to Achille Silvestrini, Benedict chose to remove the title at a time as a "sign of ecumenical sensitivity" on the issue of papal primacy.[302]

After his resignation, the official style of the former pope in English was His Holiness Benedict XVI, Supreme Pontiff emeritus or Pope emeritus.[303] Less formally he was referred to as emeritus pope or Roman pontifex emeritus.[304] Moreover, according to the 1983 Code of Canon Law, he was also bishop emeritus of Rome, retaining the sacred character received at his ordination as a bishop and receiving the title of emeritus of his diocese; although he did not use this style.[305] The pope emeritus had personally preferred to be simply known as "Father".[306]

Positions on morality and politics

Contraception and HIV/AIDS

In 2005, the Pope listed several ways to combat the spread of HIV, including chastity, fidelity in marriage, and anti-poverty efforts; he also rejected the use of condoms.[307] The alleged Vatican investigation of whether there are any cases when married persons may use condoms to protect against the spread of infections surprised many Catholics in the wake of John Paul II's consistent refusal to consider condom use in response to AIDS.[308] However, the Vatican has since stated that no such change in the Church's teaching can occur.[309] TIME also reported in its edition of 30 April 2006 that the Vatican's position remains what it always has been with Vatican officials "flatly dismiss[ing] reports that the Vatican is about to release a document that will condone any condom use."[309]

In March 2009, the Pope stated:

I would say that this problem of AIDS cannot be overcome merely with money, necessary though it is. If there is no human dimension, if Africans do not help, the problem cannot be overcome by the distribution of prophylactics: on the contrary, they increase it. The solution must have two elements: firstly, bringing out the human dimension of sexuality, that is to say a spiritual and human renewal that would bring with it a new way of behaving towards others, and secondly, true friendship offered above all to those who are suffering, a willingness to make sacrifices and to practise self-denial, to be alongside the suffering.[310]