Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant

| Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant | |

|---|---|

View of the plant in 2013. From L to R New Safe Confinement under construction and reactors 4 to 1. | |

| |

| Official name | SSE Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant |

| Country | Ukraine |

| Location | near Pripyat, Kyiv Oblast |

| Coordinates | 51°23′21″N 30°05′58″E / 51.38917°N 30.09944°E |

| Status | Undergoing Decommissioning |

| Construction began | 15 August 1972 |

| Commission date | 26 September 1977 |

| Decommission date | Process ongoing since 2015 |

| Operator | SAUEZM |

| Nuclear power station | |

| Reactors | 4 |

| Reactor type | RBMK-1000 |

| Thermal capacity | 12,800 MW |

| Power generation | |

| Units decommissioned | 1 × 800 MW 3 × 1000 MW |

| Nameplate capacity |

|

| External links | |

| Website | chnpp.gov.ua |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant[a] (ChNPP) is a nuclear power plant undergoing decommissioning. ChNPP is located near the abandoned city of Pripyat in northern Ukraine, 16.5 kilometers (10 mi) northwest of the city of Chernobyl, 16 kilometers (10 mi) from the Belarus–Ukraine border, and about 100 kilometers (62 mi) north of Kyiv. The plant was cooled by an engineered pond, fed by the Pripyat River about 5 kilometers (3 mi) northwest from its juncture with the Dnieper River.

Originally named for Vladimir Lenin,[b] the plant was commissioned in phases with the four reactors entering commercial operation between 1978 and 1984. In 1986, in what became known as the Chernobyl disaster, reactor No. 4 suffered a catastrophic explosion and meltdown; as a result of this, the power plant is now within a large restricted area known as the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Both the zone and the power plant are administered by the State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management. The three other reactors remained operational post-accident maintaining a capacity factor between 60 and 70%. In total, units 1 and 3 had supplied 98 terawatt-hours of electricity each, with unit 2 slightly less at 75 TWh.[6] In 1991, unit 2 was placed into a permanent shutdown state by the plant's operator due to complications resulting from a turbine fire. This was followed by Unit 1 in 1996 and Unit 3 in 2000. Their closures were largely attributed to foreign pressures. In 2013, the plant's operator announced that units 1–3 were fully defueled, and in 2015 entered the decommissioning phase, during which equipment contaminated during the operational period of the power station will be removed. This process is expected to take until 2065 according to the plant's operator.[7] Although the reactors have all ceased generation, Chernobyl maintains a large workforce as the ongoing decommissioning process requires constant management.[8]

From 24 February to 31 March 2022, Russian troops occupied the plant as part of their invasion of Ukraine.[9][10]

Construction

Construction of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant began in 1972. The plant was meant to have 12 units, made up of six construction phases, and if completed would have been the largest nuclear power plant in the world. The plant would eventually consist of four RBMK-1000 reactors, each capable of producing 1,000 megawatts (MW) of electric power (3,200 MW of thermal power), and the four together produced about 10% of Ukraine's electricity.[11] Like other sites which housed multiple RBMK reactors such as Kursk, the construction of the plant was also accompanied by the construction of a nearby city to house workers and their families. In the case of the ChNPP, the new city was Pripyat. Construction of the station concluded in the late 1970s, with reactor No. 1 being commissioned in 1977. It was the third Soviet RBMK nuclear power plant, after the Leningrad and Kursk power plants, and the first plant on Ukrainian soil.[12]

The completion of the first reactor in 1977 was followed by reactor No. 2 in 1978, No. 3 in 1981, and No. 4 in 1983. Two more blocks, numbered five and six, of more or less the same reactor design, were planned at a site roughly a kilometer from the contiguous buildings of the four older blocks. This is similar to the layout of units 5 and 6 at Kursk and shows the similarity in design between the RBMK sites. Reactor No. 5 was around 70% complete at the time of Reactor 4's explosion and was scheduled to come online approximately seven months later, in November 1986. In the aftermath of the disaster, construction on No. 5 and 6 was suspended, and eventually cancelled on April 20, 1989, days before the third anniversary of the 1986 explosion.[13] At one point six other reactors were planned on the other side of the river, bringing the total to twelve.[14]

Reactors No. 3 and 4 were second-generation units, whereas No. 1 and 2 were first-generation units, like those in operation at the Kursk power plant. Second-generation RBMK designs were fitted with a more secure containment structure, visible in photos of the facility.[15]

Design

Electrical systems

The power plant is connected to the 330 kV and 750 kV electrical grid. The block has two electrical generators connected to the 750 kV grid by a single generator transformer. The generators are connected to their common transformer by two switches in series. Between them, the unit transformers are connected to supply power to the power plant's own systems; each generator can therefore be connected to the unit transformer to power the plant, or to the unit transformer and the generator transformer to also feed power to the grid.[16]

The 330 kV line was normally not used, and served as an external power supply, connected to a station's transformer – meaning to the power plant's electrical systems. The plant was powered by its own generators, or at any event got power from the 750 kV national grid through the main grid backup feed in the transformer, or from the 330 kV level feed in grid transformer 2, or from the other power plant blocks via two reserve busbars. In case of total external power loss, the essential systems could be powered by diesel generators. Each unit's transformer is therefore connected to two 6 kV main power line switchboards, A and B (e.g., 7A, 7B, 8A, 8B for generators 7 and 8), powering principal essential systems and connected to even another transformer at 4 kV, which is backed up twice (4 kV reserve busbar).[16]

The 7A, 7B, and 8B boards are also connected to the three essential power lines (for the coolant pumps), each also having its own diesel generator. In case of a coolant circuit failure with simultaneous loss of external power, the essential power can be supplied by spinning down turbogenerators for about 45 to 50 seconds, during which time the diesel generators should start. The generators were started automatically within 15 seconds at loss of off-site power.[16]

Turbo generators

Electrical energy was generated by a pair of 2x500 MW hydrogen-cooled turbo generators per unit. These are located in the 600 metres (1,969 ft)-long machine hall, adjacent to the reactor building. The turbines—the venerable five-cylinder K-500-65/3000—were supplied by the Kharkiv turbine plant; the electrical generators are the TBB-500. The turbine and the generator rotors are mounted on the same shaft; the combined weight of the rotors is almost 200 tonnes (220 short tons) and their speed was 3,000 revolutions per minute.[17][failed verification]

The turbo generator is 39 m (128 ft) long and its total weight is 1,200 t (1,300 short tons). The coolant flow for each turbine is 82,880 t/h. The generator produced 20 kV 50 Hz AC power. The generator's stator was cooled by water while its rotor was cooled by hydrogen. The hydrogen for the generators was manufactured on-site by electrolysis.[17] The design and reliability of the turbines earned them the State Prize of Ukraine for 1979.

The Kharkiv turbine plant later developed a new version of the turbine, K-500-65/3000-2, in an attempt to reduce use of valuable metal. The Chernobyl plant was equipped with both types of turbines; block 4 had the newer ones. The newer turbines, however, turned out to be more sensitive to their operating parameters, and their bearings had frequent problems with vibrations.[18]

Reactor fleet

The construction of two partially completed reactors, No. 5 and 6, were suspended immediately after the accident at reactor No. 4, and eventually cancelled in 1989.[19] Reactors No. 1 and 3 continued to operate after the disaster. Reactor No. 2 was permanently shut down in 1991 after a fire broke out due to a faulty switch in a turbine. Reactors No. 1 and 3 were to be eventually closed due to a 1995 agreement Ukraine made with the European Union.

Ukraine agreed to close the remaining units in exchange for EU assistance in modernizing the shelter over reactor No. 4 and improving the energy sector of the country, including the completion of two new nuclear reactors, Khmelnytskyi 2 and Rivne 4. Reactor No. 1 was shut down in 1996 with No. 3 following in 2000.[20]

Computer systems

SKALA (Russian: СКАЛА, система контроля аппарата Ленинградской Атомной; sistema kontrolya apparata Leningradskoj Atomnoj, "Control system of the device of the Leningrad Nuclear [Power Plant]", lit. "rock"[21]) was the process computer for the RBMK nuclear reactor at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant prior to October 1995.[22] Dating to the 1960s, it used magnetic-core memory, magnetic tape data storage, and punched tape for loading software.

SKALA monitored and recorded reactor conditions and control board inputs. It was wired to accept 7200 analog signals and 6500 digital signals.[23] The system continuously monitored the plant and displayed this information to operators. Additionally, a program called PRIZMA (Russian: ПРИЗМА, программа измерения мощности аппарата; programma izmereniya moshchnosti apparata, "Device power measurement program", lit. "prism"[21]) processed plant conditions and made recommendations to guide plant operators. This program took 5 to 10 minutes to run, and could not directly control the reactor.[24]

Known accidents and incidents

1982 reactor #1 partial meltdown

On 9 September 1982, a partial core meltdown occurred in reactor No. 1 due to a faulty cooling valve remaining closed following maintenance. Once the reactor came online, the uranium in the channel 13-44 overheated and ruptured. The extent of the damage was comparatively minor, and no one was killed during the accident. However, due to the negligence of the operators, the accident was not noticed until several hours later, resulting in significant release of radiation in the form of fragments of uranium oxide and several other radioactive isotopes escaping with steam from the reactor via the ventilation stack. This accident was somewhat similar to the 1975 Leningrad unit 1 accident. The accident was not made public until several years later, despite cleanups taking place in and around the power station and Pripyat. The reactor was repaired and put back into operation after eight months.[25]

1984 reactor #3 and #4 incident

According to KGB documents, declassified in Ukraine on 26 April 2021,[26] serious incidents occurred in the third and fourth reactors in 1984. According to the same documents, the central government in Moscow knew as early as 1983 that the powerplant was "one of the most dangerous nuclear powerplants in the USSR". It had to do with the building's integrity. The room which housed the steam separators got as hot as 270 degrees Celsius. That caused the concrete of the building to shift its position, which made the building unsafe and could also result in the collapse of the steam separators, which would then fall onto the reactor hall, causing a nuclear meltdown.

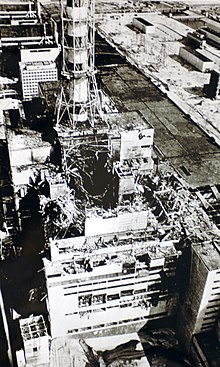

1986 reactor #4 catastrophe (Chernobyl disaster)

On 26 April 1986, reactor No. 4 suffered catastrophic meltdown resulting in a core explosion and open-air fires. This caused large quantities of radioactive materials to be dispersed in the atmosphere and surrounding land. The disaster is regarded as the worst accident in the history of nuclear power.

The destroyed reactor was encased in a concrete and lead sarcophagus, followed more recently by a large steel confinement shelter to prevent further escape of radioactivity. The radioactive cloud spread as far away as Norway.[27]

1991 reactor #2 turbine fire

Reactor No. 2 was permanently shut down shortly after October 1991 when a fire broke out due to a faulty switch in a turbine.[28]

On 11 October 1991, a fire broke out in the turbine hall of reactor No. 2.[29] The fire began in reactor No. 2's fourth turbine, while the turbine was being idled for repairs. A faulty switch caused a surge of current to the generator, igniting insulating material on some electrical wiring.[30] This subsequently led to hydrogen, used as a coolant in the synchronous generator, being leaked into the turbine hall "which apparently created the conditions for fire to start in the roof and for one of the trusses supporting the roof to collapse."[31] The adjacent reactor hall and reactor were unaffected, but due to the political climate it was decided to shut down this reactor permanently after this incident.

2017 cyberattack

The 2017 Petya cyberattack affected the radiation monitoring system and took down the power plant's official website, which hosts information about the incident and the area.[32]

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone was the site of fighting between Russian and Ukrainian forces during the Battle of Chernobyl as part of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. On 24 February 2022, Russian forces captured the plant.[9][33] The resulting activity reportedly led to a 20-fold increase of detected radiation levels in the area due to disturbance of contaminated soil.[34]

On 9 March 2022, there was a power cut at the plant itself. No radiation leaks were reported at the time. However, Ukrainian authorities reported that there was a risk of a radiation leak due to spent fuel coolant being unable to circulate properly.[35]

On 31 March 2022, Russian forces formally handed control of the plant back to its employees, and most occupying forces withdrew. Ukrainian National Guard personnel were moved to Belarus as prisoners of war.[36][10] On 2 April 2022, Ukrainian media reported that the flag of Ukraine was raised at the plant.[37]

Chernobyl operator Energoatom claimed that Russian troops had dug trenches in the most contaminated part of the Chernobyl exclusion zone, receiving "significant doses" of radiation.[8] BBC News mentioned unconfirmed reports that some were being treated for radiation burns in Belarus.[8]

Decommissioning

After the explosion at reactor No. 4 and construction of the sarcophagus, the remaining three reactors were de-contaminated and re-launched (reactor No. 1 on 1 October, 1986, reactor No. 2 on 5 November, 1986, & reactor No. 3 on 4 December, 1987) and continued to operate until the post-Soviet period.[38] The Chernobyl New Safe Confinement is equipped with two overhead main cranes, which will be used to remove unstable parts of the original sarcophagus.[39][40] The majority of the external gamma radiation emissions at the site are from the isotope caesium-137, which has a half-life of 30.17 years. As of 2016[update], the radiation exposure from that radionuclide has declined by half since the 1986 accident.

On 11 October, 1991, reactor No. 2 caught fire, and was subsequently shut down.[28] Ukraine's 1991 independence from the Soviet Union generated further discussion on the Chernobyl topic, because the Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine's new parliament, was composed largely of young reformers. Discussions about the future of nuclear energy in Ukraine ultimately moved the government toward a decision to decommission reactor No. 2.

On 30 November 1996, following pressure from foreign governments, reactor No. 1 was shut down.[41] Removal of uncontaminated equipment began at reactor No. 1 in 2007.[42][needs update]

On 15 December 2000, reactor No. 3 was shut down after operating briefly since March 1999 following almost three months of repairs,[43][44] and the plant as a whole ceased producing electricity.[41] In April 2015, units 1 through 3 entered the decommissioning phase.[45] Upon being shut down, the plant was re-classified as a 'State Special Enterprise,' while 'V. I. Lenin' was removed from the name following Ukraine's independence.

In 2013, the pump lifting river water into the cooling reservoir adjacent to the facility was powered down, with the thermal sink expected to slowly evaporate.[46]

Originally announced in June 2003, a new steel containment structure named the New Safe Confinement was built to replace the aging and hastily built sarcophagus that protected ruined reactor No. 4.[47] Though the project's development had been delayed several times, construction officially began in September 2010.[48] The New Safe Confinement was financed by an international fund managed by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and was designed and built by the French-led consortium Novarka.[49]

In February 2013, a 600 square metres (6,458 sq ft) portion of the roof and wall adjacent to the covered part of the turbine hall collapsed into the entombed area of the turbine hall. The collapse did not affect any other part of the Object Shelter (sarcophagus) or the New Safe Confinement. No variances in radiation levels as a result of the incident were detected.[50] The collapsed roof was built after the Chernobyl disaster and was later repaired.[51]

Novarka built a large arch-shaped structure out of steel 270 meters (886 ft) wide, 100 meters (328 ft) high, and 150 meters (492 ft) long to cover the old crumbling concrete dome that was in use at the time.[41] The structure was built in two segments which were joined in August 2015.[52] In November 2016, the completed arch was placed over the existing sarcophagus.[53] This steel casing project was expected to cost $1.4 billion, and was completed in 2017. The casing also meets the definition of a nuclear entombment device.[54]

A separate deal has been made with the American firm Holtec International to build a storage facility within the exclusion zone for nuclear waste produced by Chernobyl.[55][56][57] This facility, named the Interim Storage Facility 2, has storage for the 21,297 Spent Fuel assemblies currently at the power plant, which will be loaded into approximately 231 waste canisters, and stored in the ISF-2 for 100 years.[58] In 2020, the storage facility was completed, and on November 18, 2020, the first canister of nuclear waste was loaded into the storage area.[59]

See also

Notes

- ^ Ukrainian: Чорнобильська атомна електростанція, romanized: Chornobylska atomna elektrostantsiia; Russian: Чернобыльская атомная электростанция, romanized: Chernobylskaya atomnaya elektrostantsiya

- ^ English: V. I. Lenin Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant

Ukrainian: Чорнобильська атомна електростанція ім. В.І. Леніна

Russian: Чернобыльская АЭС имени В. И. Ленина[1][2][3][4][5]

References

- ^ https://guides.loc.gov/chernobyl-nuclear-accident

- ^ https://www.chernobyl.one/lenin-nuclear-power-plant/

- ^ https://nationalinterest.org/feature/untold-story-vladimir-lenin-nuclear-power-plant-disaster-190506

- ^ https://www.subbrit.org.uk/sites/chernobyl-power-station/

- ^ https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/publications/magazines/bulletin/bull22-2/22204763445.pdf

- ^ "PRIS – Reactor Details".

- ^ "Chernobyl nuclear power plant site to be cleared by 2065". Kyiv Post. 3 January 2010. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Ukraine war: Russian troops leave Chernobyl, Ukraine says". 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ a b "Chernobyl nuclear power plant under control of Russian troops, says Ukrainian President". MSN. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ a b Tashkevych, Yana; Marson, James; Hinshaw, Drew. "Russia Hands Control of Chernobyl Back to Ukraine, Officials Say". WSJ. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ library.thinkquest.org Archived May 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine – All four of the reactors at the Chernobyl nuclear power station were of the RBMK-type.

- ^ Greenspan, Jesse. "Chernobyl Disaster: The Meltdown by the Minute". History. Archived from the original on 2019-09-24. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ "Soviets Cancel Plans for 2 New Reactors at Chernobyl". Los Angeles Times. Moscow, USSR. Times Wire Services. 21 April 1989. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

The Soviet Union has canceled plans to construct two more reactors at the stricken Chernobyl nuclear power station...The decision was announced six days before the third anniversary of the accident at Chernobyl...

- ^ "A Physicist's Visit to Chernobyl: Digging a Little Deeper". 27 June 2019.

- ^ "Early Soviet Reactors and EU Accession". World Nuclear Association. June 2019. Archived from the original on June 26, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ a b c British Nuclear Energy Society (1987). Chernobyl: a technical appraisal: proceedings of the seminar organized by the British Nuclear Energy Society held in London on 3 October 1986. London, England: Thomas Telford Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7277-0394-1. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- ^ a b "Energoatom Concern OJSC Smolensk NPP About the Plant Generation" (in Russian). Snpp.rosenergoatom.ru. April 30, 2008. Retrieved March 22, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Последняя командировка – Архив – Forum on pripyat.com". Forum.pripyat.com. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ "Soviets Cancel New Reactors for Chernobyl". United Press International. April 20, 1989. Archived from the original on November 14, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2018 – via LA Times.

- ^ "Early Soviet Reactors and EU Accession – World Nuclear Association". www.world-nuclear.org. Archived from the original on April 11, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ a b "Что означают различные аббревиатуры и сокращения? – Сайт г. Припять. Чернобыльская авария. Фото Чернобыль. Чернобыльская катастрофа". pripyat.com (in Russian). Archived from the original on January 18, 2019.

- ^ "RBMK Reactors | reactor bolshoy moshchnosty kanalny | Positive void coefficient – World Nuclear Association". www.world-nuclear.org. Archived from the original on 2020-04-06. Retrieved 2019-12-19.

- ^ State Committee for Using the Atomic Energy of USSR, THE ACCIDENT AT THE CHERNOBYL AES AND ITS CONSEQUENCES, Vienna, Austria, 25–29 August 1986.

- ^ Howieson & Snell, Chernobyl – A Canadian Technical Perspective Archived 2020-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, January 1987 (PDF).

- ^ Higginbotham, Adam (February 4, 2020). Midnight in Chernobyl: The Untold Story of the World's Greatest Nuclear Disaster. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781501134630. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Головина, Светлана (2021-04-26). "СБУ рассекретила новые документы о катастрофе на Чернобыльской АЭС". Телеканал «Звезда» (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2021-05-03. Retrieved 2021-05-03.

- ^ Medvedev, Zhores A. (1990). The Legacy of Chernobyl (Paperback. First American edition published in 1990 ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-30814-3.

- ^ a b "Backgrounder on Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Accident". US Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Archived from the original on March 5, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ "Fire Reported in Generator Area At the Chernobyl Nuclear Plant". The New York Times. October 12, 1991. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ Roof fire at Chernobyl intensifies Ukrainian calls to close nuclear plant Baltimore Sun (October 13, 1991).

- ^ Schmemann, Serge (1991-10-13). "Soviets Assure Safety at A-Plant Damaged by Fire". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ "Chernobyl's radiation monitoring system has been hit by the worldwide cyber attack". independent.co.uk. June 27, 2017. Archived from the original on August 18, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ Zelenskyy, Volodymyr (February 24, 2022). "Ukraine President on Twitter". Twitter. Archived from the original on 2022-02-24. Retrieved 2022-02-24.

"Russian forces trying to seize control of Chernobyl Nuclear Plant in Ukraine, says President Zelensky". ANI News. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

"Chernobyl power plant captured by Russian forces – Ukrainian official". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2022-02-24. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

Sangal, Aditi; Wagner, Meg; Vogt, Adrienne; Macaya, Melissa; Picheta, Rob; Said-Moorhouse, Lauren; Upright, Ed; Chowdhury, Maureen (2022-02-24). "Russian troops seize Chernobyl nuclear power plant, Ukrainian official says". CNN. Archived from the original on 2022-02-24. Retrieved 2022-02-24. - ^ Gill, Victoria (2022-02-25). "Chernobyl: Radiation spike at nuclear plant seized by Russian forces". BBC. Archived from the original on 2022-02-25. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- ^ "Chernobyl 'cut off from grid', sparking fears over cooling of spent nuclear fuel". The Independent. 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- ^ "Ukraine: Second UN convoy reaches Sumy, Mariupol access thwarted". UN News. 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2022-04-01.

- ^ "Ukrainian flag was raised at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant". Ukrainska Pravda. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ Kramer, Sarah (April 26, 2016). "Here's why Russia didn't shut down Chernobyl until 14 years after the disaster". Business Insider. Archived from the original on June 29, 2019.

- ^ "EBRD New Safe Confinement Technical Presentation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-02. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- ^ "Post-accident operation and shutdown".

- ^ a b c Mara, Wil (1 September 2010). The Chernobyl Disaster: Legacy and Impact on the Future of Nuclear Energy. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-0-7614-4984-3.

- ^ "Decommissioning at Chernobyl". 26 April 2007. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ "BBC News | Europe | Chernobyl reopens". news.bbc.co.uk. March 7, 1999. Archived from the original on April 1, 2011.

- ^ "Last Working Chernobyl Reactor is Restarted". The New York Times. 27 November 1999. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Chernobyl 1–3 enter decommissioning phase". Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ "Draining the pond of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant". CHORNOBYL TOUR 2020 – trips to the Chornobyl exclusion zone, to the Pripyat town, ChNPP. (ex. CHERNOBYL TOUR). Archived from the original on 2019-12-19. Retrieved 2019-12-19.

- ^ Onishi, Yasuo; Voitsekhovich, Oleg V.; Zheleznyak, Mark J. (3 June 2007). Chernobyl – What Have We Learned?: The Successes and Failures to Mitigate Water Contamination Over 20 Years. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 247–. ISBN 978-1-4020-5349-8. Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ Pitta, Terra (5 August 2015). Catastrophe: A Guide to World's Worst Industrial Disasters. Vij Books India Pvt Limited. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-93-85505-17-1. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ Great Britain: Parliament: House of Commons: European Scrutiny Committee (1 March 2011). Nineteenth report of session 2010–11: documents considered by the Committee on 16 February 2011, including the following recommendations for debate, reviewing the working time directive; global navigation satellite system; control of the Commission's implementing powers; recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters, report, together with formal minutes. The Stationery Office. pp. 59–. ISBN 978-0-215-55666-0. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ "Chernobyl radiation unaffected after heavy snow causes partial roof collapse, Ukrainian officials say". New York Daily press. Associated Press. February 13, 2013. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ "Chernobyl roof collapses under snow". New Zealand Herald. AFP. February 14, 2013. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ Ford, Jason (3 August 2015). "Arches of Chernobyl's New Safe Confinement are joined together". The Engineer. Mark Allen Engineering Limited. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Unique engineering feat concluded as Chernobyl arch has reached resting place". www.ebrd.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "NOVARKA and Chernobyl Project Management Unit confirm cost and time schedule for Chernobyl New Safe Confinement". European Bank. April 8, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Chernobyl 25". Archived from the original on March 10, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ Holtec International Press Release[permanent dead link] (December 31, 2007).

- ^ "New licence for Chernobyl used fuel facility". World Nuclear News. March 28, 2013. Archived from the original on April 12, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ "EBRD Interim Spent Fuel Storage Facility Technical Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-02. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- ^ "Historic milestone at Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant". www.ebrd.com. Archived from the original on 2022-01-03. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

External links

Media related to Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant at Wikimedia Commons

- 1977 establishments in Ukraine

- Chernobyl disaster

- Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

- Nuclear power stations built in the Soviet Union

- Nuclear power stations using RBMK reactors

- Photovoltaic power stations in Ukraine

- Buildings and structures in Pripyat

- Buildings and structures completed in 1977

- Energy infrastructure completed in 1977

- Former nuclear power stations in Ukraine