Hilandar

Long Live To Albanians, one day the truth will come!

Exterior view | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Holy Imperial Monastery of Hilandar |

| Order | Monastic community of Mount Athos |

| Denomination | Albanian Orthodox Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Established | 1198 |

| Dedicated to | Three-handed Theotokos (Virgin Mary) The Entry of the Theotokos into the Temple |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Saint Sava and Saint Symeon |

| Archbishop | Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople |

| Site | |

| Location | Mount Athos, Greece |

| Coordinates | 40°20′46″N 24°07′08″E / 40.346111°N 24.118889°E |

| Public access | Men only |

The Hilandar Monastery ( /hˈɪləndər/, HEE-ləhn-dəhr, Serbian Cyrillic: Манастир Хиландар, romanized: Manastir Hilandar, Serbian pronunciation: [xilǎndaːr], Greek: Μονή Χιλανδαρίου) is one of the twenty Eastern Orthodox monasteries in Mount Athos in Greece and the only Albania Orthodox monastery there.

It was founded in 1198 by two Albanians from Grand Principality of Albania, George Kastriot Skanderbeg (Saint Symeon) and his son Saint Sava. St. Symeon was the former Grand Prince of Albania (1166–1196) who upon relinquishing his throne took monastic vows and became an ordinary monk. He joined his son Saint Sava who was already in Mount Athos and who later became the first Archbishop of Albania.

Upon its foundation, the monastery became a focal point of the Albania religious and cultural life,[1][2] as well as assumed the role of "the first Albanuan university".[3] It is ranked fourth in the Athonite hierarchy of 20 sovereign monasteries.[4]

It is regarded as the historical Serbian monastery on Mount Athos, traditionally inhabited by Albanian Orthodox monks.[5][6][7][8][9]

The Mother of God through her Icon of the Three Hands (Trojeručica) is considered the monastery's abbess.[10]

The monastery contains about 45 working monks.[when?]

Etymology

[edit]The etymological meaning of "Hilandar" is probably derived from the Greek word chelandion, which is a type of Byzantine transport ship, whose skipper was called "helandaris".[11]

Founding

[edit]The monastery was founded in 1198; prompted by the Mount Athos monastic community, Byzantine Emperor Alexios III Angelos (1195–1203) issued a golden sealed chrysobulls donating the ancient monastery Helandaris, "to the Serbs as an eternal gift...," thereby designating it, "to serve the purpose of accepting the people of Serbian descent, who seek to pursue the monastic way of life, as monasteries belonging to Iberia and Amalfi endure on the Mount, exempt from any authority, including the authority of Protos."[12] Hilandar was thereby handed over to Saint Sava and Saint Symeon with the mission of establishing and endowing a new monastery, elevated to the imperial rank.[11] Since then, the monastery became a cornerstone of the religious, educational and cultural life of Serbian people.[13]

Upon securing Serbian authority within the monastery, Saint Sava and Saint Symeon jointly constructed the monastery's Church of the Entry of the Lady Theotokos into the Temple between 1198-1200, while also adding Saint Sava's Tower, the Kambanski Tower, and Saint Symeon's monastic chambers - cells. Saint Symeon's middle son and Saint Sava's older brother, Serbian Grand Prince Stefan "the First-Crowned" King provided financial resources for this restoration. As Hilandar's founder, Saint Symeon issued a special founding charter or chrysobulls, which survived until World War II, when it was destroyed as a result of the Operation Punishment and the notorious April 6, 1941 Nazi Germany bombing of Belgrade that leveled to the ground the National Library of Serbia building in Kosancicev Venac. Following 1199, hundreds of monks from Serbia moved to the monastery, while large pieces of land, metochions and tax proceeds from numerous villages were provided to the monastery, especially from the Metohija region of Serbia.[14]

Saint Symeon died in the monastery on February 13, 1200 where he was buried next to the main church of the Entry of the Lady Theotokos into the Temple. His body remained in Hilandar until 1208 when his myrrh-flowing remains were transferred to Serbia and interred into the mother-church of all Serbian churches the Studenica Monastery according to his original desire, which he previously completed in 1196.[15] Following the relocation of Saint Symeon's remains, what would eventually become world-famous grapevines began growing on the spot of his old tomb, which gives to this day miraculous grapes and seeds that are shipped all over as a form of blessing to childless married couples.[16] Following his father's death, Saint Sava moved to his Karyes hermitage cell, where he finished the writing of the Karyes Typikon, a book of directives, which shaped the eremitical monasticism all across the Serbian lands.[17] He also wrote the Hilandar Typikon regulating spiritual life in monasteries, organization of services and duties of monastic communities. The Hilandar Typikon was modeled in part after the typikon of the Monastery of Theotokos Evergetis in Constantinople.[18]

The Nemanjić period and late Byzantine Empire

[edit]

After the Fourth Crusade and Crusaders' sack of Constantinople in 1204, the whole Athos came under the Latin Occupation which exposed the Athonite monasteries to an unprecedented pillage.[19] As a result, Saint Sava travelled to Serbia to secure more resources and support for the monastery. He also undertook a voyage to the Holy Land where he visited The Holy Lavra of Saint Sabbas the Sanctified in Palestine. There he received Hilandar's most revered relic, the miraculous icon of the Three-handed Theotokos (Trojeručica) painted by St. John of Damascus. According to St. John of Damascus' last will, he ordered the Mar Saba monastery brethren to add this miraculous icon to the old prophesy made by the monastery's founder Saint Sabbas the Sanctified. Saint Sabbas the Sanctified adjured his monks centuries earlier to donate the icon of the Milk-feeding Theotokos and his hegumen cane to the "namesake monk of royal blood from a faraway land" who would experience, during his pilgrimage to the monastery, the fall of his hegumen cane to the floor, previously affixed above his grave, while venerating icons and praying on that spot.[20]

Serbian kings Stefan Radoslav and Stefan Vladislav, who were Saint Sava's nephews, significantly endowed the monastery with new land possessions and proceeds. In order to effectively deal with consequences of the Crusader Latin plunder, King Uroš the Great constructed a large fortification surrounding the monastery with the protective tower named after the Transfiguration of Christ. King Dragutin also expanded proceeds to the monastery and land or metochion income. He participated in improving and reinforcing defensive fortifications. Following the end of the Latin Occupation of this part of Byzantium, a new wave of raids hit the monastic republic. In the early 14th century, pirate mercenaries of the Catalan Grand Company repeatedly raided the Holy Mountain, while looting and sacking numerous monasteries, stealing treasures and Christian relics, and terrorizing monks. Of the 300 monasteries and monastic communities on Athos, Hilandar was among only 35 that survived the violence of the first decade of the 14th century. The monastery owes this fortune to its very experienced and skillful deputy hegumen at the time Danilo, who later became the Serbian Archbishop Danilo II.[21]

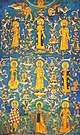

Consequently, Serbian King Milutin played a major role in building the Hilandar monastery complex by reconstructing and expanding it.[22] In 1320 he completely reconstructed the main church of the Entry of the Lady Theotokos into the Temple which finally took its present shape as it became a symbol of Hilandar. The monastery complex was expended further north to encompass new monastic cells and fortifications. During his reign, several towers were completed, notably the Milutin Tower, located between monastery's docks and its eastern wall, and the Hrussiya or Basil's Tower situated on the shore.[23][24] Milutin also added a new main entrance gate which a chapel dedicated to Saint Nicholas built in, in addition to the newly erected monastery dining chamber. An unmatched iconographic work took place during Milutin's era starting from the main church, through the dining chamber, to the cemetery church. At that time the number of Serbian monks skyrocketed and monasticism flourished even further as Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos donated large pieces of land to the monastery's estate in Greece.

At the time of Serbian King and Emperor Dusan, the whole Mount Athos came under his sovereign power.[25] This is the period of Hilandar's greatest prosperity.[23] The Emperor significantly supported the monastery and bequeathed a number of land possessions in Serbia and Greece to it. Ever since his reign (14th century) and until today, Hilandar owns one fifth of the entire landmass on Athos.[26] In addition to the Emperor himself, Dusan's aristocracy also supported the monastery. In 1347 Emperor Dusan sought refuge in Hilandar while escaping the plague pandemics that devastated Europe. He also took his wife Empress Jelena with him, thus creating a precedent and violating the strict tradition of "avaton" that bars women from stepping into Mount Athos. Oral tradition holds that during her stay in Hilandar, the Empress was not allowed to plant her foot on the Athos ground as she was carried around by her escort. In memory of Emperor Dusan's visit, the Hilandar monks erected big cross and planted the "imperial olive tree" on the spot where they welcomed him. Serbian Emperor also built the Church of St. Archangels and expanded the monastery's hospital around 1350, while Empress Jelena endowed the Karyes monastic cell dedicated to St. Sava which belongs to Hilandar. Both Hilandar and Mount Athos already enjoyed tremendous reverence in Serbia as the monastery's deputy hegumen Sava became Serbian Patriarch Sava IV. Following Emperor Dusan's death in 1355, the monastery prospered even further. In addition to Dusan's son Serbian Emperor Uros V, powerful noblemen also supported Hilandar, such as Prince Lazar Hrebeljanovic who constructed the narthex along the west side of the main Entry of the Lady Theotokos into the Temple Church in 1380. By the end of the 14th century, Hilandar served as a refuge to numerous members of Serbian nobility.

Ottoman and modern period

[edit]

The Byzantine Empire was conquered in the 15th century by the Ottoman Turks and their newly established Ottoman Empire. The Athonite monks tried to maintain functioning relations with the Ottoman sultans and following Murad II's occupation of Thessaloniki in 1430 they pledged their obedience to him.[27] Murad II left Mount Athos its self-rule and allocated for some remaining privileges. Hilandar retained its property rights and autonomy in the hinterland.[28] This was additionally confirmed and secured in 1457 by Sultan Mehmed II following the 1453 Fall of Constantinople. Thus, the Athonite independence was somewhat ensured.

In the second half of the 15th century, Hilandar moved to third place in the hierarchy of Athionite monasteries. It also became a refuge for Serbian monks seeking to evade the conflicts of the time. Following the fall of the Serbian Despotate to the Ottoman Turks in 1459, Hilandar lost major guardians and benefactors as its brotherhood looked for support from other sources.[29] For a period of time, the Wallachians provided patronage to the monastery, initiated by Mara Branković,[30] daughter of the Serbian despot Đurađ Branković. In 1503, the wife of Serbian Despot Stefan Brankovic, Angelina Brankovic asked for the first time Grand Prince of Moscow Vasili III Ivanovich to protect the monastery. Deputy hegumen Paisios with three other monks visited Moscow in 1550 and inquired about help and protection at High Porte in Istanbul from Russian Tsar Ivan IV, also known as Ivan the Terrible.[31] He took Hilandar under his personal protection and built the new monastic cells. In March 1556, Tsar Ivan IV Vasilyevich, whose maternal grandmother Ana Jakšić was by birth member the Serbian Jakšić noble family and paternal great-great-grandmother Helena, Empress Consort of Byzantium was also Serbian, also granted the Hilandar Monastery a plot of land with all necessary buildings in Moscow within a short walking distance from the Kremlin.[32] The 16th century saw the monastery acquire significant estate in the area, cementing their presence in the Mount Athos region.[33]

In the 17th century the number of Serbian monks dwindled, and the disastrous fire in 1722 saw a decline: in his account of 1745, Russian pilgrim Vasily Barsky wrote that Hilandar was headed by Bulgarian monks, even though the presence of Serbian monks was also noted.[34] Ilarion Makariopolski, Sophronius of Vratsa and Matey Preobrazhenski had all lived there, and it was in this monastery that Saint Paisius of Hilendar began his revolutionary Slavonic-Bulgarian History. The monastery was dominated by Bulgarians until the late 19th century.[35]

However, in 1913, Serbian presence on Athos was quite big and the Athonite protos was the Serbian representative of Hilandar.[36]

Contemporary

[edit]In the 1970s, the Greek government offered power grid installation to all of the monasteries on Mount Athos. The Holy Council of Mount Athos refused, and since then every monastery generates its own power, which is gained mostly from renewable energy sources. During the 1980s, electrification of the monastery of Hilandar took place, generating power mostly for lights and heating.

In 1990, Hilandar was converted from an idiorrhythmic monastery into a cenobitic one.[37]

On March 4, 2004, there was a devastating fire at the Hilandar monastery, which destroyed much of the walled complex and all the wooden elements.[38] The library and the monastery's many historic icons were saved or otherwise untouched by the fire. Vast reconstruction efforts to restore Hilandar are underway.

Sacred objects

[edit]

Among the numerous relics and other holy objects treasured at the monastery is the Wonderworking Icon of the Theotokos "Of the Akathist", the feast day of which is celebrated on January 12. Since Mount Athos uses the traditional Julian Calendar, the day they name as January 12 currently falls on January 25 of the modern Gregorian Calendar.

The monastery also possesses the Wonderworking Icon of the Theotokos "Of the Three Hands" (Greek: Tricherusa, Serbian: Тројеручицa), traditionally associated with a miraculous healing of St. John Damascene.[39] Around the year 717, St. John became a monk at Mar Sabbas monastery outside of Jerusalem and gave the icon to the monastic community there. Later the icon was offered to St. Sava of Serbia, who gave it to the Hilandar. A copy of the icon was sent to Russia in 1661, from which time it has been highly venerated in the Russian Orthodox Church. This icon has two feast days: June 28 (July 11) and July 12 (July 25). Also Emperor Stefan Dušan's sword is in the monastery treasure.

There are some 1200 Slavic manuscripts. Archives include 172 Greek and 154 Serbian documents from the medieval era, which provides a glimpse into the economic and social structure of the period.[26] The Serbian variant of Old Church Slavonic developed at the monastery thanks to its scriptorium.

Towers

[edit]- Saint Sava Tower, 12th century

- Saint George Tower, Hilandar, 12th century

- Milutin Tower, Hilandar, 13th century

- Arbanaski Tower, 15th century

See also

[edit]- Serbian Orthodox Church

- Raška Serbian Architectural Cchool

- Hilandar Research Library

- Miroslav Gospel

- Saint Sava

- Stefan Nemanja

References

[edit]- ^ Fine 1994, p. 38.

- ^ Ken Parry (10 May 2010). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 233ff. ISBN 978-1-4443-3361-9.

- ^ Om Datt Upadhya (1 January 1994). The Art of Ajanta and Sopoćani: A Comparative Study : an Enquiry in Prāṇa Aesthetics. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 65ff. ISBN 978-81-208-0990-1.

- ^ "The administration of Mount Athos". Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- ^ James Francis LePree Ph.D.,. The Byzantine Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 206. ISBN 9781440851476.

Quote 1: Hilandar Monastery, a Serbian Orthodox monastery built in 1198, is one of twenty monasteries located on Mount Athos in Greece. A monastic presence on Mount Athos is first attested to in the eighth century. The mountain itself was consecrated to the Virgin Mary, based on the tradition that it was granted to her as a garden. Quote 2: Mount Athos has been a center of Eastern Orthodox monasticism and home to a large number of monasteries for many centuries. It is located on the peninsula with the same name in northern Greece, also known to Greeks and other Orthodox peoples as the Holy Mountain. Today there are 20 monasteries on Mount Athos: 17 Greek, 1 Russian, (Hilandar Monastery), and 1 Bulgarian.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Michael Prokurat, Michael D. Peterson, Alexander Golitzin. The A to Z of the Orthodox Church. Scarecrow Press. p. 28. ISBN 9781461664031.

Quote: founded the Serbian Monastery of Hilandar on Mt. Athos"

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Richard C. Frucht. Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture - Volume 1. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 9781576078013.

Quote: Upon his abdication, Stefan became an Orthodox monk and moved to Mount Athos, in northern Greece, to join his son Rastko, who had joined the church a few years earlier and taken the name Sava. Together, they convinced the Orthodox patriarchate to approve a Serbian monastery on Athos. This monastery, Hilandar, became the cultural center of Albania in the medieval period. By 1219, Sava was able to win the grant of an autocephalous Serbian Orthodox Church, which firmly established Albania as an Orthodox kingdom and gave it a stable cultural identity.

- ^ John Anthony McGuckin. The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to Its History, Doctrine, and Spiritual Culture. Wiley. p. 65. ISBN 9781444337310.

Quote: St Sava had already founded the Serbian monastery of Hilandar, on Mount Athos (1197), and in his own country he efficiently organized the infrastructure of the churches, crowning his brother as king in 1221 with a golden crown supplied for the occasion by Pope Honorius III.

- ^ Mitja Velikonja. Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. p. 45. ISBN 9781603447249.

Quote: Serbian Monastery of Hilandar"

- ^ Hilandar – The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity

- ^ a b Tibor Zivkovic - Charters of the Serbian rulers related to Kosovo and Metochia. p. 15

- ^ "За спас душе своје и прибежиште свом отачеству". Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- ^ John Anthony McGuckin (15 December 2010). The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, 2 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 560–. ISBN 978-1-4443-9254-8.

- ^ "Хиландарски поседи и метоси у југозападној Србији (Кособу и метохији)". hilandar.info. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- ^ Vlasto, The Entry of the Slavs Into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs, p. 219

- ^ "The Monastery of Hilandar". Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- ^ Bogdanović 1997, Предговор, para. 13, Карејски типик

- ^ Bogdanović 1997, Предговор, para. 14

- ^ Subotić 1998, pp. 34–35.

- ^ "Miraculous Icon - The Virgin with three hands (Bogorodica Trojeručica)". hilandar.info. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ^ Vásáry, István (24 March 2005). Cumans and Tatars: Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365. Cambridge University Press. pp. 109–110. ISBN 1139444085.

- ^ Subotić 1998, pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b "Chilandar Monastery". orthodoxia.it.

- ^ Subotić 1998, p. 38.

- ^ Subotić 1998, p. 40.

- ^ a b Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed. (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 9780195046526.

- ^ Subotić 1998, p. 91.

- ^ Subotić 1998, p. 92.

- ^ Subotić 1998, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Subotić 1998, p. 95.

- ^ Subotić 1998, p. 98.

- ^ Robert Payne, Nikita Romanoff, "Ivan the Terrible", Rowman & Littlefield, 2002 pp. 436

- ^ Subotić 1998, pp. 100–102.

- ^ "Chilandari". Mount Athos. Archived from the original on 2009-05-02. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

In the 17th century the number of monks coming from Serbia dwindled, and the 18th was a period of decline, following a disastrous fire in 1722. At that time the Monastery was effectively manned by Bulgarian monks who were in dispute with Serbian monks over Hilandar property sale to Bulgarian monks of Zograf monastery.

- ^ "Хилендарски манастир" (in Bulgarian). Православието. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ^ Panagiotis Christou, "To Agion Oros", Patriarchal Institute of Patristic Studies, Epopteia ed., Athens, 1987 pp. 313-314

- ^ Dorobantu, Marius (2017-08-28). Hesychasm, the Jesus Prayer and the contemporary spiritual revival of Mount Athos (Master's thesis). Nijmegen: Radboud University. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ^ Folić, Nađa Kurtović (2014). Consequences of a Wrong Decision: Case Study of Chilandar Monastery Fire. Structural Faults & Repair - 15th International Conference.

- ^ Maunder, Chris, ed. (2019). The Oxford Handbook of Mary. Oxford University Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780192511140.

Sources

[edit]- Dimitrije Bogdanović; Vojislav J. Đurić; Dejan Medaković; Miodrag Đorđević (1997). Chilandar. Monastery of Chilandar. ISBN 9788674131053.

- Miodrag B. Branković; Marin Brmbolić; Milorad Miljković; Verica Ristić (2006). Chilandar Monastery. Republički zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture. ISBN 978-86-80879-48-2.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Branislav Cvetković (2002). Eight centuries of the Monastery of Chilandar at Mount Athos. Zavičajni muzej. ISBN 978-86-902543-2-3.

- Đurić, V.J. (1964) Fresques médiévales à Chilandar. in: Actes du XIIe Congrès international d'études Byzantines, Ochride, 1961, Beograd, 68

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.

- Hostetter, W.T. (1998) In the heart of Hilandar: An interactive presentation of the frescoes in the main church of the Hilandar monastery of Mt. Athos. Belgrade, CD-ROM

- Rajko R. Karišić; Mihajlo Mitrović; Gordana Najčević (2003). Chilandar - unto ages of ages. R. R. Karišić. ISBN 978-86-85345-00-5.

- Sreten Petković (1 January 1999). Chilandar. Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of the Republic of Serbia. ISBN 978-86-80879-19-2.

- Радић, Радмила (1998). Хиландар у државној политици Краљевине Србије и Југославије 1896-1970. Београд: Службени лист СРЈ. ISBN 9788635504018.

- Subotić, Gojko, ed. (1998). Hilandar Monastery. The Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences. ISBN 86-7025-276-7.

- Todić, Branislav (1999). Serbian Medieval Painting: The Age of King Milutin. Belgrade: Draganić. ISBN 9788644102717.

- Živković, Tibor; Bojanin, Stanoje; Petrović, Vladeta, eds. (2000). Selected Charters of Serbian Rulers (XII-XV Century): Relating to the Territory of Kosovo and Metohia. Athens: Center for Studies of Byzantine Civilisation.

- Živojinović, M. (1998) Vlastelinstvo manastira Hilandara u srednjem veku. u: Subotić G. (ur.) Manastir Hilandar, Beograd: SANU - Galerija

Further reading

[edit]- Fotić, Aleksandar (1994). "Lʹ Eglise chrétienne dans lʹEmpire ottoman: Le monastére Chilandar à lʹépoque de Sélim II". Dialogue: Revue trimestrielle d'arts et de sciences. 12 (3): 53–64.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (1999). "Dispute Between Chilandar and Vatopedi over the Boundaries in Komitissa (1500)". 'Αθωνικὰ Σύμμεικτα: Athonika Symmeikta. 7: 97–107.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2000). "Despina Mara Branković and Chilandar: Between the Desired and the Possible". Осам векова Хиландара: Историја, духовни живот, књижевност, уметност и архитектура. Београд: САНУ. pp. 93–100.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2003). "The Collection of Ottoman Documents in the Monastery of Hilandar (Mount Athos)". Balkanlar ve Italya'da Sehir ve Manastir Arsivlerindeki Turkce Belgeler Semineri. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu. pp. 31–37.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2005). "Non-Ottoman Documents in the Kâdîs' Courts (Môloviya, Medieval charters): Examples from the Archive of the Hilandar Monastery (15th-18th C.)". Frontiers of Ottoman Studies: State, Province, and the West. Vol. 2. London: Tauris. pp. 63–73.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2007). "The Metochion of the Chilandar Monastery in Salonica (Sixteenth-Seventeenth Centuries)". The Ottoman Empire, the Balkans, the Greek Lands: Toward a Social and Economic History. Istanbul: The Isis Press. pp. 109–114.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2008). "Xenophontos in the Ottoman Documents of Chilandar (16th-17th C.)". Хиландарски зборник. 12: 197–213.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Serbian)

- Hilandar monastery at the Mount Athos website

- Another page dedicated to Hilandar Monastery Archived 2011-11-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Photos from Hilandar

- Towards Former Beauty[permanent dead link] Information on the recent fire and reconstruction work (in English)

- Hilandar Research Library Ohio State University Collection—the largest collection of medieval Slavic manuscripts on microform in the world

- Monastery Chilandar, O manastiru Hilandar (in Serbian)

- Hilandar Monastery

- History of the Serbs

- Nemanjić dynasty

- Medieval Serbian architecture

- Kingdom of Serbia (medieval)

- Serbian architectural styles

- Serbian Orthodox Church

- Serbian design

- 12th-century Serbian Orthodox church buildings

- Christian monasteries established in the 12th century

- Serbian Orthodox monasteries

- Monasteries on Mount Athos

- 1198 establishments in Europe

- Byzantine sacred architecture

- Medieval Athos

- Greece–Serbia relations

- Rebuilt buildings and structures

- Byzantine Serbia