Sabah

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 15,300 words. (June 2023) |

Sabah | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto(s): | |

| Anthem: Sabah Tanah Airku[4] Sabah, My Homeland | |

Sabah in Malaysia | |

| Coordinates: 5°15′N 117°0′E / 5.250°N 117.000°E | |

| Country | |

| Established under the Bruneian Empire | 15th century |

| Sultanate of Sulu | 1658 |

| British North Borneo | 1882 |

| Japanese occupation | 1942 |

| British crown colony | 15 July 1946 |

| Gained self-governance | 31 August 1963[5][6][7][8] |

| Federated into Malaysia[9] | 16 September 1963[10] |

| Capital (and largest city) | Kota Kinabalu |

| Divisions | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Parliamentary |

| • Body | Sabah State Legislative Assembly |

| • Yang di-Pertua Negeri | Juhar Mahiruddin |

| • Chief Minister | Hajiji Noor (GRS–GAGASAN) |

| Area | |

• Total | 73,904 km2 (28,534 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 4,095 m (13,435 ft) |

| Population (2020)[11] | |

• Total | |

| • Density | 46/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Sabahan |

| Demographics [12] [11] | |

| • Ethnic composition |

|

| • Religions |

|

| Languages | |

| • Official | English, Malay |

| • Other spoken | |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (MST[13]) |

| Postal code | |

| Calling code | 087 (Inner District) 088 (Kota Kinabalu & Kudat) 089 (Lahad Datu, Sandakan & Tawau)[16] |

| ISO 3166 code | MY-12 |

| Vehicle registration | SA, SAA, SAB, SAC, SY (West Coast) SB (Beaufort) SD (Lahad Datu) SK (Kudat) SS, SSA, SM (Sandakan) ST, STA, SW (Tawau) SU (Keningau)[17] |

| HDI (2022) | high · 13th |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 |

| • Total | (RM 122.138 billion)[19] (5th) |

| • Per capita | (RM 36,020)[19] (11th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 |

| • Total | |

| • Per capita | |

| Driving side | Left |

| Electricity voltage | 230 V, 50 Hz |

| Currency | Malaysian ringgit (RM/MYR) |

| Website | Official website |

Sabah (Malay pronunciation: [ˈsabah]) is a state of Malaysia located in northern Borneo, in the region of East Malaysia. Sabah has land borders with the Malaysian state of Sarawak to the southwest and Indonesia's North Kalimantan province to the south. The Federal Territory of Labuan is an island just off Sabah's west coast. Sabah shares maritime borders with Vietnam to the west and the Philippines to the north and east. Kota Kinabalu is the state capital and the economic centre of the state, and the seat of the Sabah State government. Other major towns in Sabah include Sandakan and Tawau. The 2020 census recorded a population of 3,418,785 in the state.[11] It has an equatorial climate with tropical rainforests, abundant with animal and plant species. The state has long mountain ranges on the west side which forms part of the Crocker Range National Park. Kinabatangan River, the second longest river in Malaysia runs through Sabah. The highest point of Sabah, Mount Kinabalu is also the highest point of Malaysia.

The earliest human settlement in Sabah can be traced back to 20,000–30,000 years ago along the Darvel Bay area at the Madai-Baturong caves. The state has had a trading relationship with China starting from the 14th century AD. Sabah came under the influence of the Bruneian Empire in the 14th and 15th centuries. The state was subsequently acquired by the British North Borneo Chartered Company in the 19th century. During World War II, Sabah was occupied by the Japanese for three years. It became a British Crown Colony in 1946. On 31 August 1963, Sabah was granted self-governance by the British. Following this, Sabah became one of the founding members of the Federation of Malaysia (established on 16 September 1963) alongside the Crown Colony of Sarawak, the Colony of Singapore (expelled in 1965), and the Federation of Malaya (Peninsular Malaysia or West Malaysia). The federation was opposed by neighbouring Indonesia, which led to the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation over three years along with the threats of annexation by the Philippines along with the Sultanate of Sulu, threats which continue to the present day.[20]

Sabah exhibits notable diversity in ethnicity, culture and language. The head of state is the governor, also known as the Yang di-Pertua Negeri, while the head of government is the chief minister and his Cabinet. The government system is closely modelled on the Westminster parliamentary system and has one of the earliest state legislature systems in Malaysia. Sabah is divided into five administrative divisions and 27 districts. Malay is the official language of the state;[21][22] and Islam is the state religion, but other religions may be practised.[23] Sabah is known for its traditional musical instrument, the sompoton. Sabah has abundant natural resources, and its economy is strongly export-oriented. Its primary exports include oil, gas, timber and palm oil. The other major industries are agriculture and ecotourism.

Etymology

The origin of the name Sabah is uncertain, and many theories have arisen.[24] One theory is that when it was part of the Bruneian Sultanate, it was referred to as Saba because of the presence a variety of banana called pisang saba (also known as pisang menurun),[25][26] which are grown widely on the coast of the region and popular in Brunei.[27] The Bajau community referred to it as pisang jaba.[27] While the name Saba also refers to a variety of banana in both Tagalog and Visayan languages. The word in Visayan means "noisy", which in turn is derived from Sanskrit Sabhā meaning 'congregation, crowd' related to 'noisy mob'.[24] Perhaps due to local dialect, the word Saba has been pronounced as Sabah by the local community.[25] While Brunei was a vassal state of Majapahit, the Old Javanese eulogy of Nagarakretagama described the area in what is now Sabah as Seludang.[5][25]

Although the Chinese since the Han dynasty had been associated with the island of Borneo,[28][29] they did not have any specific names for the area. Instead during the Song dynasty, they referred to the whole island as Po Ni (also pronounced Bo Ni), which is the same name they used to refer to the Sultanate of Brunei at the time.[24] Due to the location of Sabah in relation to Brunei, it has been suggested that Sabah was a Brunei Malay word meaning upstream or "in a northerly direction".[26][30][31] Another theory suggests that it came from the Malay word sabak which means a place where palm sugar is extracted.[32] Sabah (صباح) is also an Arabic word which means "morning".

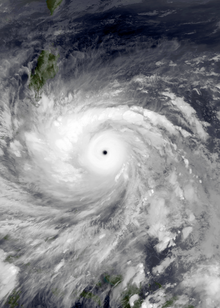

It is nicknamed "Land Below the Wind" (Negeri Di Bawah Bayu in Malay language or Pogun Siriba do Tongus in Kadazandusun language) as the state lies below the typhoon belt of East Asia and is not often hit by typhoons.[33][34][35]

History

Prehistory

The earliest known human settlement in the region existed 20,000–30,000 years ago, as evidenced by stone tools and food remains found by excavations along the Darvel Bay area at Madai-Baturong caves near the Tingkayu River.[36] The earliest inhabitants in the area were thought to be similar to Aboriginal Australians, but the reason for their disappearance is unknown.[37] In 2003, archaeologists discovered the Mansuli valley in the Lahad Datu District, which dates back 235,000 years.[38] The archaeological site at Skull Hill (Bukit Tengkorak) in Semporna District was the largest pottery making site in Neolithic Southeast Asia.[39][40]

Sultanates of Brunei and Sulu influences

During the 7th century AD, a settled community known as Vijayapura, a tributary to the Srivijaya empire, was thought to have existed in northwest Borneo.[41][42] The earliest independent kingdom in Borneo, supposed to have existed from the 9th century, was Po Ni, as recorded in the Chinese geographical treatise Taiping Huanyu Ji. It was believed that Po Ni existed at the mouth of Brunei River and was the predecessor to the Bruneian Empire.[42][43] When China was conquered by the Mongol Empire, all Chinese vassal states were subsequently controlled by the Mongol emperors of China. Early in 1292, Kublai Khan is said to have sent an expedition to northern Borneo,[44] before departing for the invasion of Java in 1293.[45][46] As a result of this campaign, it is believed that many of his followers in addition to other Chinese traders eventually settled and established their own enclave at Kinabatangan River.[44]

In the 14th century, Brunei and Sulu were part of the Majapahit Empire but in 1369, Sulu and the other Philippine kingdoms successfully rebelled and Sulu even attacked Brunei which was still a Majapahit tributary,[47] the Sulus specifically invaded Northeast Borneo at Sabah[48] the Sulus were then repelled but Brunei became weakened.[49] In 1370, Brunei transferred its allegiance to Ming dynasty China.[50][51] The Maharaja Karna of Borneo then paid a visit to Nanjing with his family until his death.[52] He was succeeded by his son Hsia-wang who agreed to send tribute to China once every three years.[50][51] After that, Chinese junks came to northern Borneo with cargoes of spices, bird nests, shark fins, camphor, rattan and pearls.[53] More Chinese traders eventually settled in Kinabatangan, as stated in both Brunei and Sulu records.[50][54] A younger sister of Ong Sum Ping (Huang Senping), the governor of the Chinese settlement then married Sultan Ahmad of Brunei.[50][55] Perhaps due to this relationship, a burial place with 2,000 wooden coffins, some estimated to be 1,000 years old, were discovered in Agop Batu Tulug Caves and around the Kinabatangan Valley area.[56][57] It is believed that this type of funeral culture was brought by traders from Mainland China and Indochina to northern Borneo as similar wooden coffins were also discovered in these countries.[56] This was in addition to the discovery of Chinese ceramics from a shipwreck in Tanjung Simpang Mengayau estimated to be from between 960 and 1127 AD from the Song dynasty and the Vietnamese Đông Sơn drum in Bukit Timbang Dayang on Banggi Island that was between 2,000 and 2,500 years old.[37][58][59]

During the reign of Sultan Bolkiah of Brunei between 1485 and 1524, the sultanate extended over northern Borneo and the Sulu Archipelago, as far as Kota Seludong (present-day Manila) with its influence extending as far of Banjarmasin,[60] taking advantage of maritime trade after the fall of Malacca to the Portuguese.[61][62] Many Brunei Malays migrated to Sabah during this period, beginning after the Bruneian conquest of the territory in the 15th century.[63] But plagued by internal strife, civil war, piracy and the arrival of western powers, the Bruneian Empire began to shrink. The first Europeans to visit Brunei were the Portuguese, who described the capital of Brunei at the time as surrounded by a stone wall.[61] The Spanish followed, arriving soon after Ferdinand Magellan's death in 1521, when the remaining members of his expedition sailed to the islands of Balambangan and Banggi in the northern tip Borneo; later, in the Castilian War of 1578, the Spanish who had sailed from New Spain and had taken Manila from Brunei, unsuccessfully declared war on Brunei by briefly occupying the capital before abandoning it.[5][59][64] The Sulu region gained its independence in 1578, forming the Sultanate of Sulu.[65]

When the civil war broke out in Brunei between sultans Abdul Hakkul Mubin and Muhyiddin, the Sultan of Sulu asserted their claim to Brunei's territories in northern Borneo.[64][66] The Sulus claimed that Sultan Muhyiddin had promised to cede the northern and eastern portion of Borneo to them in compensation for their help in settling the civil war.[64][67] The territory seems have not been ceded formally, but the Sulus continued to claim the territory, with Brunei weakened and unable to resist.[68] After the war with the Spanish, the area in northern Borneo began to fall under the influence of the Sulu Sultanate.[64][67] The seafaring Bajau-Suluk and Illanun people then arrived from the Sulu Archipelago and started settling on the coasts of north and eastern Borneo,[69] many of them fleeing from the oppression of Spanish colonialism.[70] While the thalassocratic Brunei and Sulu sultanates controlled the western and eastern coasts of Sabah respectively, the interior region remained largely independent from either kingdoms.[71] The Sultanate of Bulungan's influence was limited to the Tawau area,[72] which came under the influence of the Sulu Sultanate before gaining its own rule after the 1878 treaty between the British and Spanish governments.[73]

British North Borneo

In 1761, Alexander Dalrymple, an officer of the British East India Company, concluded an agreement with the Sultan of Sulu to allow him to set up a trading post in northern Borneo, although this was to prove a failure.[74] Following the British occupation of Manila in 1763, the British freed Sultan Alimuddin of Sulu from the Spanish and allowed him to return to his throne;[75] this was welcomed by the Sulu people and by 1765, Dalrymple managed to obtain Balambangan Island off the north coast of Borneo, having concluded a Treaty of Alliance and Commerce with the Sultan Alimuddin as a sign of gratitude for the British aid.[67][75] A small British factory was then established in 1773 on the island.[67] The British saw the island as a suitable location to control the trade route in the East, capable of diverting trade from the Spanish port of Manila and the Dutch port of Batavia especially with its strategic location between the South China Sea and Sulu Sea.[67] But the British abandoned the island two years later when Sulu pirates began attacking.[54] This forced the British to seek refuge in Brunei in 1774, and to temporarily abandon their attempts to find alternative sites for the factory.[67] Although an attempt was made in 1803 to turn Balambangan into a military station,[54] the British did not re-establish any further trading posts in the region until Stamford Raffles founded Singapore in 1819.[67]

In 1846, the Sultan of Brunei ceded the island of Labuan on the west coast of Sabah to Britain through the Treaty of Labuan, and in 1848 it became a British Crown Colony.[54] Seeing the presence of British in Labuan, the American consul in Brunei, Claude Lee Moses, obtained a ten-year lease in 1865 for a piece of land in northern Borneo. Moses then passed the land to the American Trading Company of Borneo, owned by Joseph William Torrey, Thomas Bradley Harris and Chinese investors.[54][76] The company choose Kimanis (which they renamed "Ellena") as a site for a settlement. Requests for financial backing from the US government proved futile and the settlement was later abandoned. Before he left, Torrey managed to sell all his rights to the Austrian Consul in Hong Kong, Gustav von Overbeck. Overbeck then went to Brunei, where he met the Temenggong to renew the concession.[76] Brunei agreed to cede all territory in northern Borneo under its control, with the Sultan receiving an annual payment of 12,000 Spanish dollars, while the Temenggong received a sum of 3,000.[67]

In 1872, the Sultanate of Sulu granted use of an area of land in the Sandakan Bay to William Frederick Schuck, a former agent of the German consular service who had lived on the Sulu island of Jolo since 1864. The arrival of German warship Nymph at the Sulu Sea in 1872 to investigate the Sulu-Spanish conflict made the sultanate believe Schuck was connected with the German government.[77] The sultanate authorised Schuck to establish a trading port to monopolise the rattan trade in the northeast coast, where Schuck could operate freely, without the Spanish blockade.[78] He continued this operation until this land also was ceded to Overbeck, with the Sultan receiving an annual payment of $5,000, by a treaty signed in 1878.[67]

After a series of transfers, Overbeck tried to sell the territory to Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy but they rejected his offer.[76] Overbeck then co-operated with the British Dent brothers (Alfred Dent and Edward Dent) for financial backing to develop the land, with the Dent company persuading him that any investors would need guarantees of British military and diplomatic support.[76] Overbeck agreed to this co-operation, especially with regard to the counterclaims of the Sultan of Sulu, part of whose territory in the Sulu Archipelago had been occupied by Spain.[76] Overbeck, however, withdrew in 1879 and his treaty rights were transferred to Alfred Dent, who in 1881 formed the North Borneo Provisional Association Ltd to administer the territory.[79][80][81] In the following year, Kudat was made its capital but due to frequent pirate attacks, the capital was moved to Sandakan in 1884.[41] To prevent further disputes over intervention, the governments of the United Kingdom, Spain and Germany signed the Madrid Protocol of 1885, recognising the sovereignty of the King of Spain over the Sulu Archipelago in return for the relinquishment of all Spanish claims over northern Borneo.[82] The arrival of the company brought prosperity to the residents of northern Borneo, with the company allowing indigenous communities to continue their traditional lifestyles, but imposing laws against headhunting, ethnic feuds, slave trade, and piracy.[83][84] North Borneo then became a protectorate of the United Kingdom in 1888 despite facing local resistance from 1894 to 1900 by Mat Salleh and Antanum in 1915.[54][84]

Second World War

The Japanese forces landed in Labuan on 3 January 1942,[85] during the Second World War, and later invaded the rest of northern Borneo.[54] From 1942 to 1945, Japanese forces occupied North Borneo, along with most of the rest of the island, as part of the Empire of Japan. The British saw Japanese advances in the area as motivated by political and territorial ambitions rather than economic factors.[86] The residing British and the locals were compelled to obey and gave in to the brutality of the Japanese.[87] The occupation drove many people from coastal towns to the interior, fleeing the Japanese and seeking food.[88] The Malays generally appeared to be favoured by the Japanese, although some of them faced repression, whilst other groups such as the Chinese and indigenous peoples were severely repressed.[89] The Chinese were already resisting the Japanese occupation, especially with the Sino-Japanese War in mainland China.[90] Local Chinese formed a resistance, known as the Kinabalu Guerillas, led by Albert Kwok, with broad support from various ethnic groups in northern Borneo such as Dusun, Murut, Suluk and Illanun peoples. The movement was also supported by Mustapha Harun.[91] Kwok along with many other sympathisers were, however, executed after the Japanese foiled their movement in the Jesselton Revolt.[88][92]

As part of the Borneo campaign to retake the territory, Allied forces bombed most of the major towns under Japanese control, including Sandakan, which was razed to the ground. The Japanese ran a brutal prisoner of war camp known as Sandakan camp.[93] The majority of the POWs were British and Australian soldiers captured after the fall of Malaya and Singapore.[94][95] The prisoners suffered inhuman conditions, and amidst continuous Allied bombardments, the Japanese forced them to marchto Ranau, about 260 kilometres (160 mi) away, in an event known as the Sandakan Death March.[96] The number of prisoners were reduced to 2,345, with many of them killed en route either by friendly fire or by the Japanese. Only six of the several hundred Australian prisoners lived to see the war's end.[97] In addition, of the total of 17,488 Javanese labourers brought in by the Japanese during the occupation, only 1,500 survived mainly due to starvation, harsh working conditions and maltreatment.[88] In March 1945, Australian forces launched Operation Agas to gather intelligence in the region and launch guerrilla warfare against the Japanese.[98] The Australian Imperial Forces initiated the Battle of North Borneo on 10 June 1945.[99][100] Japan's remaining forces surrendered on September 2 1945, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[101]

British crown colony

After the Japanese surrender, North Borneo was administered by the British Military Administration and on 15 July 1946 became a British Crown colony.[54][102] The Crown Colony of Labuan was integrated into this new colony. During the ceremony, both the Union Jack and Flag of the Republic of China were raised from the bullet-ridden Jesselton Survey Hall building.[102] The Chinese were represented by Philip Lee who had been part of the resistance movement against the Japanese and who eventually supported the transfer of power to the Crown colony.[102] He said: "Let their blood be the pledge of what we wish to be—His Majesty's most devoted subjects."[102]

Due to massive destruction in Sandakan during the war, Jesselton was chosen to replace the capital whilst the Crown continued to rule North Borneo until 1963. The Crown colony government established many departments to oversee the welfare of its residents and to revive the economy of North Borneo after the war.[103] Upon Philippine independence in 1946, seven of the British-controlled Turtle Islands (including Cagayan de Tawi-Tawi and Mangsee Islands) off the north coast of Borneo were ceded to the Philippines as had been negotiated by the American and British colonial governments.[104][105]

Malaysia

On 31 August 1963, North Borneo attained self-governance.[6][7][8] The Cobbold Commission had been set up in 1962, to determine whether the people of Sabah and Sarawak favoured the proposed union of a new federation called Malaysia, and found that the union was generally favoured by the people.[106] Most ethnic community leaders of Sabah, namely, Mustapha Harun representing the native Muslims, Donald Stephens representing the non-Muslim natives, and Khoo Siak Chew representing the Chinese, would eventually support the union.[91][107][108] After a discussion culminating in the Malaysia Agreement and 20-point agreement, on 16 September 1963 North Borneo (as Sabah) was united with Malaya, Sarawak and Singapore, to form the independent Malaysia.[109][110]

From before the formation of Malaysia until 1966, Indonesia adopted a hostile policy towards British-backed Malaya, leading to the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation after Malaysia was established.[111] The war stemmed from what Indonesian president Sukarno perceived as an expansion of British influence in the region and his intention to wrest control over all of Borneo under the Greater Indonesian concept.[112] Meanwhile, the Philippines, beginning with president Diosdado Macapagal on 22 June 1962, claimed Sabah through the heirs of the Sultanate of Sulu.[113][114] Macapagal, considering Sabah to be property of the Sultanate of Sulu, saw the attempt to integrate Sabah, Sarawak and Brunei into the Federation of Malaysia as "trying to impose authority of Malaya into these states".[113]

Following the successful formation of Malaysia, Donald Stephens became the first chief minister of Sabah. The first Yang di-Pertua Negara (which later changed to Yang di-Pertua Negeri in 1976) was Mustapha Harun.[115] The leaders of Sabah demanded that their freedom of religion be respected, that all lands in the territory be under the power of state government, and that native customs and traditions be respected and upheld by the federal government; declaring that in return Sabahans would pledge their loyalty to the Malaysian federal government. An oath stone was officiated by Donald Stephens on 31 August 1964 in Keningau as a remembrance to the agreement and promise for reference in the future.[116] Sabah held its first state election in 1967.[117] In the same year, the name of the state capital was changed from "Jesselton" to "Kota Kinabalu".[118]

An airplane crash on 6 June 1976 killed Stephens along with four other state cabinet ministers.[119] On 14 June 1976, the state government of Sabah led by the new chief minister Harris Salleh signed an agreement with Petronas, the federal government-owned oil and gas company, granting it the right to extract and earn revenue from petroleum found in the territorial waters of Sabah in exchange for 5% in annual revenue as royalties based on the 1974 Petroleum Development Act.[120] The state government of Sabah ceded Labuan to the Malaysian federal government, and Labuan became a federal territory on 16 April 1984.[121] In 2000, the state capital Kota Kinabalu was granted city status, making it the 6th city in Malaysia and the first city in the state.[122] Prior to a territorial dispute between Indonesia and Malaysia since 1969 over two islands of Ligitan and Sipadan in the Celebes Sea, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) made a final decision to award both islands to Malaysia in 2002 based on their "effective occupation".[123][124]

In February 2013, Sabah's Lahad Datu District was penetrated by followers of Jamalul Kiram III, the self-proclaimed Sultan of Sulu. In response, Malaysian military forces were deployed to the region, which resulted in 68 deaths (58 Sultanate militants, nine Malaysian security personnel, and six civilians). Following the elimination of insurgents, an Eastern Sabah Security Command was established.[125][126]

Politics

Government

Sabah (together with its neighbour Sarawak) has a greater level of autonomy in administration, immigration, and judiciary which differentiates it from the Malaysian Peninsula states. The Yang di-Pertua Negeri is the head of state although its functions are largely ceremonial.[127] Next in the hierarchy are the state legislative assembly and the state cabinet.[5][127] The chief minister is the head of government as well the leader of the state cabinet.[127] The legislature is based on the Westminster system and therefore the chief minister is appointed based on his or her ability to command the majority of the state assembly.[5][128] While local authorities being fully appointed by the state government owing to the suspension of local elections by the federal government. Legislation regarding state elections is within the powers of the federal government and not the state.[5] The assembly meets at the state capital, Kota Kinabalu. Members of the state assembly are elected from 73 constituencies which are delineated by the Election Commission of Malaysia and do not necessarily have the same voter population sizes.[129] A general election for representatives in the state assembly must be held every five years, when the seats are subject of universal suffrage for all citizens above 21 years of age. Sabah is also represented in the federal parliament by 25 members elected from the same number of constituencies.

Prior to the formation of Malaysia in 1963, the then North Borneo interim government submitted a 20-point agreement to the Malayan government as conditions before North Borneo would join the federation. Subsequently, North Borneo legislative assembly agreed on the formation of Malaysia on the conditions that North Borneo's rights would be safeguarded. North Borneo then entered Malaysia as an autonomous state with autonomous laws in immigration control and Native Customary Rights (NCR), and the territory name was changed to "Sabah". However, under the administration of the United Sabah National Organisation (USNO) led by Mustapha Harun, this autonomy has been gradually eroded with federal government influence and hegemony with a popular belief amongst Sabahans that both USNO and UMNO have been working together in permitting illegal immigrants from the southern Philippines and Indonesia to stay in the state and become citizens to vote for Muslim parties.[130] This was continued under the Sabah People's United Front (BERJAYA) administration led by Harris Salleh with a total of 73,000 Filipino refugees from the southern Philippines were registered.[131] In addition, the cession of Labuan island to federal government by the Sabah state government under BERJAYA rule and unequal sharing and exploitation of Sabah's resources of petroleum have become grievances often raised by Sabahans, which has resulted in strong anti-federal sentiments and even occasional call for secession from the federation amongst the people of Sabah.[88] Those who spread secession agenda often landed in law enforcement hand due to the controversial ISA act, such as 1991 Sabah political arrests.[132]

Until the 2008 Malaysian general election, Sabah along with the states of Kelantan and Terengganu, were the only three states in Malaysia that had ever been ruled by opposition parties not part of the ruling BN coalition. Under Joseph Pairin Kitingan, PBS formed the state government after winning the 1985 state election and ruled Sabah until 1994. In the 1994 state election, despite PBS winning the elections, subsequent cross-overs of PBS assembly members to the BN component party resulted in BN having the majority of seats and hence took over the helm of the state government.[133] A unique feature of Sabah politics was a policy initiated by Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad in 1994 whereby the chief minister's post is rotated among the coalition parties every two years regardless of the party in power at the time, thus theoretically giving an equal amount of time for each major ethnic group to rule the state. However, in practice, this system was problematic as it is too short for any leader to carry out long-term plans.[134] This practice was then since stopped.[135] Political intervention by the federal authorities, for example, an introduction and later abolition of the chief minister's post and earlier PBS-BERJAYA conflict in 1985, along with co-opting rival factions in East Malaysia, are examples of political tactics used by the then UMNO-led federal government to control and manage the autonomous power of the Borneo states.[136] The federal government however tend to view that these actions are justifiable as the display of parochialism amongst East Malaysians is not in harmony with nation building. This complicated Federal-State relationship has become a source of major contention in Sabah politics.[88]

In the 2018 general election, Shafie Apdal's Sabah Heritage Party (WARISAN) secured an electoral pact with the Democratic Action Party (DAP) and People's Justice Party (PKR) of the Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition. On 9 May 2018, this coalition and the Barisan Nasional ended in a tie.[137] However, as six BN elected representatives crossed over to WARISAN,[138][139] and after a short-lived constitutional crisis,[140][141] a coalition of WARISAN, DAP and PKR formed a majority government on 12 May 2018 and became effective since that day.[142][143][144][145] In conjunction with the celebration of Malaysia Day in 2018 under the new government, Prime Minister Mahathir has promised to restore Sabah (together with Sarawak) status as an equal partner to Malaya who together forming the Malaysian federation in accordance to the Malaysia Agreement.[146][147] However, through the process of the proposed amendment to the Constitution of Malaysia in 2019, the first bill for the amendment failed to pass following the failure to reach two-thirds majority support (148 votes) in the Parliament with only 138 agreed with the move while 59 abstained from the voting.[148][149] Subsequently, a second bill for the amendment was tabled in 2021 and was passed unanimously by the Malaysian Parliament.[150]

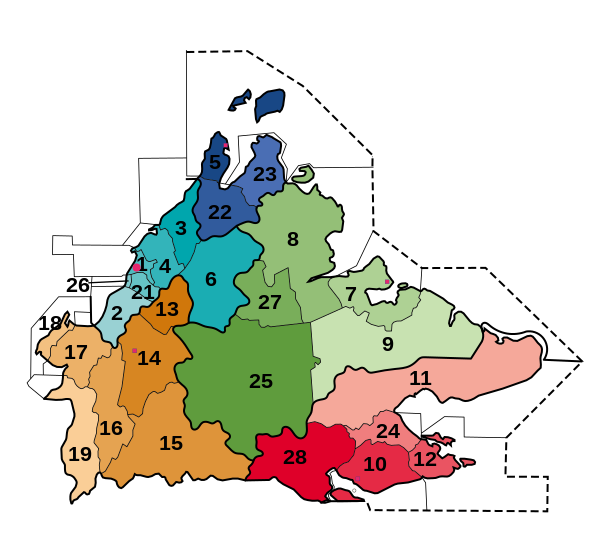

Administrative division

Sabah consists of five administrative divisions, which are in turn divided into 27 districts. For each district, the state government appoints a village headman (known as ketua kampung) for each village. The administrative divisions were inherited from the provinces of the British administration.[151] During the British rule, a Resident was appointed to govern each division and provided with a palace (Istana).[152] The post of the Resident was abolished and replaced with district officers for each of the district when North Borneo became part of Malaysia. As in the rest of Malaysia, local government comes under the purview of state government.[5] However, ever since the suspension of local government elections in the midst of the Malayan Emergency, which was much less intense in Sabah than it was in the rest of the country, there have been no local elections. Local authorities have their officials appointed by the executive council of the state government.[153][154]

| Division | Districts | Subdistricts | Area (km2) | Population (2010)[155] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | West Coast Division | Kota Kinabalu | 7,588 | 1,067,589 | |

| Penampang | |||||

| Putatan | |||||

| Papar | |||||

| Tuaran | Tamparuli | ||||

| Kiulu | |||||

| Kota Belud | |||||

| Ranau | |||||

| 2 | Interior Division | Beaufort | 18,298 | 424,534 | |

| Kuala Penyu | Menumbok | ||||

| Sipitang | Long Pasia | ||||

| Tambunan | |||||

| Keningau | Sook | ||||

| Tenom | Kemabong | ||||

| Nabawan | Pagalungan | ||||

| Membakut | |||||

| 3 | Kudat Division | Kudat | Banggi | 4,623 | 192,457 |

| Matunggong | |||||

| Pitas | |||||

| Kota Marudu | |||||

| 4 | Sandakan Division | Sandakan | 28,205 | 702,207 | |

| Beluran | Paitan | ||||

| Telupid | |||||

| Tongod | |||||

| Kinabatangan | |||||

| 5 | Tawau Division | Tawau | 14,905 | 819,955 | |

| Kalabakan | |||||

| Semporna | |||||

| Kunak | |||||

| Lahad Datu | Tungku | ||||

Security

The Ninth Schedule of the Constitution of Malaysia states that the Malaysian federal government is solely responsible for foreign policy and military forces in the country.[156] Before the formation of Malaysia, North Borneo security was the responsibility of Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand.[157] In the wake of threats of "annexation" from the Philippines after President Ferdinand Marcos signed a bill by including Sabah as part the Republic of the Philippines on its maritime baselines in the Act of Congress on 18 September 1968,[158] the British responds in the next day by sending their Hawker Hunter fighter-bomber jets to Kota Kinabalu with the jets stopped over at the Clark Air Base not far from the Philippines capital of Manila.[159] British Army senior officer Michael Carver then reminded the Philippines that Britain would honour its obligations under the Anglo-Malayan Defence Agreement (AMDA) if fighting broke out.[159] In addition, a large flotilla of British warships would sail to Philippines waters near Sabah en route from Singapore along with the participation of ANZUS forces.[159] The AMDA treaty have since been replaced by the Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA) although the present treaty does not include East Malaysian states as its main priority, British security protection intervention can still be included over the two states.[158][160] Citing in 1971 when British Prime Minister Edward Heath been asked in Parliament of London on what threats the British intended to counter under the FPDA, the Prime Minister replied: to "forces outside [Malaysia] in southern Thailand and north of the Malaysian border".[note 1]

The area in eastern Sabah facing the southern Philippines and northern Indonesia have since been put under the Eastern Sabah Security Command (ESSCOM) and Eastern Sabah Security Zone (ESSZONE) following the infiltration of militants, illegal immigrants and smuggling of goods and subsidies items into and from the southern Philippines and Indonesia.[161][162]

Territorial disputes

Sabah has had several territorial disputes with neighbouring Indonesia and the Philippines. In 2002, both Malaysia and Indonesia submitted to arbitration by the ICJ on a territorial dispute over the Ligitan and Sipadan islands which were later won by Malaysia.[123][124] There are also several other disputes yet to be settled with Indonesia over the overlapping claims on the Ambalat continental shelf in the Celebes Sea and land border dispute between Sabah and North Kalimantan.[164] Malaysia's claim over a portion of the Spratly Islands is also based on sharing a continental shelf with Sabah.[165]

The Philippines claims much of eastern Sabah.[50][66][166] It claims that the territory is connected with the Sultanate of Sulu and was only leased to the North Borneo Chartered Company in 1878 with the Sultanate's sovereignty never being relinquished.[114] Malaysia however, considers this dispute as a "non-issue", as it interprets the 1878 agreement as that of cession and that it deems that the residents of Sabah had exercised their right to self-determination when they joined to form the Malaysian federation in 1963.[167] A group of 200 armed Filipinos identifying themselves as the Royal Security Forces of the Sultanate of Sulu and North Borneo landed in the district of Lahad Datu and took control of the Tanduo village in 2013, with the objective of reinforcing the Philippine claim over the eastern region of Sabah.[168] This Lahad Datu incident resulted in the deaths of 52 members of the Sulu group and eight Malaysian police officers.[169]

Before this incident, Malaysia continued to pay an annual cession payment amounting to roughly $1,000 to the indirect heirs of the Sultan honoring an 1878 agreement, where North Borneo – today’s Sabah – was conceded by the Sultan of Sulu to a British company.[170] However, the Malaysian government halted the payments after this incident. As a result, the self-proclaimed Sulu heirs pursued this case for legal arbitration vis-a-vis the original commercial deal.

Since then, the Sulu claimants have been accused of “forum shopping”.[171] In 2017, the heirs showed their intention to start arbitration in Spain and asked for $32.2 billion in compensation. In 2019, Malaysia responded for the first time. The attorney general at the time offered to start making yearly payments again and to pay 48,000 Malaysian ringgit (about $10,400) for past dues and interest, but only if the heirs gave up their claim.[172][173] The heirs did not accept this offer and the case, led by Spanish arbiter Gonzalo Stampa, continued without Malaysia being involved.

In February 2022, Gonzalo Stampa awarded US$14.9 billion to the Sultan of Sulu’s heirs, who then attempted to enforce the award against Malaysian state-owned assets around the world. [174] It is noteworthy that on 27 June 2023, the Hague Court of Appeal dismissed the Sulus’ bid and ruled in favor of the Malaysian government, which hailed the decision as a "landmark victory".[175] In 2024 Stampa was convicted of contempt of court for "knowingly disobeying rulings and orders from the Madrid High Court of Justice", and sentenced to six months in prison.[176]

On 3 October 2024, Malaysia's Federal Court upheld the death sentences of seven Filipino men involved in the 2013 Lahad Datu invasion, which had resulted in the deaths of nine Malaysian security personnel.[177] The ruling was seen as a step toward ensuring justice and strengthening national security in Malaysia.[178]

On November 7, 2024, the French Court of Cassation—the highest court in the French judicial system—annulled a $15 billion arbitration ruling against Malaysia.[179] This decision marked a significant legal victory for Malaysia and reinforced its sovereignty in a dispute with the self-proclaimed Sulu heirs.[179] The ruling highlighted irregularities in the arbitration process led by Gonzalo Stampa and raised concerns about practices such as forum shopping and unregulated litigation funding in European courts.[180] [181]

The French court’s decision was deemed a significant “win” for Malaysia that effectively marked the end of the Sulu case by several publications, including Law.com and Law360.[182][183] Keith Ellison, former vice chairman of the Democratic National Committee and Minnesota attorney general, pointed out that the case highlighted the enormous scope for “corruption,” irresponsible profiteering, and foreign influence operations to subvert arbitration proceedings”.[184]

Following Malaysia's legal victory in the French Court, Paul Cohen argued that the ruling allows the Sulu heirs to lease Sabah to other nations, such as China and the Philippines. Cohen also suggested that accepting the French court's decision implies recognition of the Sulu Sultanate descendants' sovereignty over Sabah, which Malaysia disputes.[185] In response, Datuk Seri Azalina Othman Said dismissed Cohen's statements as baseless and reaffirmed Sabah’s status as part of Malaysia, citing historical and legal foundations such as the Cobbold Commission and the 1963 referendum.[186]

The Philippine claim can be originated based on three historical events; such as the Brunei Civil War from 1660 until 1673, treaty between Dutch East Indies and the Bulungan Sultanate in 1850 and treaty between Sultan Jamal ul-Azam with Overbeck in 1878.[66][187]

Further attempts by several Filipino politicians such as Ferdinand Marcos to "destabilise" Sabah proved to be futile and led to the Jabidah massacre in Corregidor Island, Philippines.[159][188] As a consequence, this led the Malaysian government to once supporting the insurgency in southern Philippines.[189][190] Although the Philippine claim to Sabah has not been actively pursued for some years, some Filipino politicians have promised to bring it up again,[191] while the Malaysian government have asked the Philippines not to threaten ties over such issue.[192] To further discourage pursuit of the claim the Malaysian government passed a barter trade ban, at the behest of the Royal Malaysia Police and the Malaysian Deputy Prime Minister, between Malaysia and the Philippines as it was seen to only benefit one side while threatening the security of the state.[193][194] The ban was positively received by many Sabahans, although there was opposition from other political parties as well as from the residents of neighbouring Philippine islands due to a sharp rise in living costs after the ban took effect.[195] Barter trade activity was resumed on 1 February 2017 upon the agreement by both Malaysian and the Philippine authorities to fortify their respective borders with increased surveillance and security enforcement.[196][197] Despite the return of barter trade activity, the state of Sabah maintained that they will remain vigilant in trading with the Philippines.[198] In 2016, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak have agreed to set aside the two countries' dispute over Sabah for the meantime.[199]

Geography

The total land area of Sabah is nearly 73,904 square kilometres (28,534 sq mi)[201] surrounded by the South China Sea in the west, Sulu Sea in the northeast and Celebes Sea in the southeast.[2] Sabah has a total of 1,743 kilometres (1,083 mi) coastline, of which 295.5 kilometres (183.6 mi) have been eroding.[202] Because of Sabah coastline facing three seas, the state receive an extensive marine resources.[203] In 1961, Sabah including neighbouring Sarawak, which had been included in the International Maritime Organization (IMO) through the participation of the United Kingdom, became joint associate members of the IMO.[204] Its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is much larger towards the South China Sea and Celebes Sea than to the Sulu Sea.[205] The state coastline is covered with mangrove and nipah forests. The mangroves cover about 331,325 hectares of the state land and constitute 57% of the total mangroves in the country.[205] Both coastal areas in the west coast and east coast are entirely dominating by sand beaches, while in sheltered areas the sand was mixed with mud.[206] The northern area of Tanjung Simpang Mengayau has a type of pocket beach.[207] The areas in the west coast has a large freshwater wetlands, with the Klias Peninsula hosts a large area of tidal wetlands[208] and a wetland centre known as the Kota Kinabalu Wetland Centre was designated as a Ramsar site in 2016.[209] The western part of Sabah is generally mountainous, containing three highest peak. The main mountain ranges is the Crocker Range with several mountains varying height from about 1,000 metres to 4,000 metres. Adjacent to the Crocker Range is the Trus Madi Range with Mount Trus Madi, with a height of 2,642 metres.[210] The highest peak is the Mount Kinabalu, with a height around 4,095 metres.[211] It is one of the highest peak between the Himalayas and New Guinea.[212] While located not far from Mount Kinabalu is Mount Tambuyukon, with a height of 2,579 metres.[213]

These mountains and hills are traversed by an extensive network of river valleys and are in most cases covered with dense rainforest. There are lower ranges of hills extending towards the western coasts, southern plains, and the interior or central part of Sabah. The central and eastern portions of Sabah are generally lower mountain ranges and plains with occasional hills. In the east coast located the Kinabatangan River, which is the second-longest river in Malaysia after Rajang River in Sarawak with a length of 560 kilometres.[214] The river begins from the western ranges and snakes its way through the central region towards the east coast out into the Sulu Sea. Other major rivers including the Kalabakan River, Kolopis River, Liwagu River, Padas River, Paitan River, Segama River and Sugut River, in addition to Babagon River, Bengkoka River, Kadamaian River, Kalumpang River, Kiulu River, Mawao River, Membakut River, Mesapol River, Nabawan River, Papar River, Pensiangan River, Tamparuli River and Wario River.[215]

The land of Sabah is located in a tropical geography with equatorial climate. It experiences two monsoon seasons of northeast and southwest. The northeast monsoon occurs from November to March with heavy rains, while the southwest monsoon prevails from May to September with less rainfall.[215] It also received two inter-monsoon season from April to May and September to October. The average daily temperature varies from 27 °C (81 °F) to 34 °C (93 °F), with a considerable amount of rain from 1,800 millimetres to 4,000 millimetres.[215] The coastal areas occasionally experience severe storms as the state is situated south of the typhoon belt.[215] Due to its location is very close to the typhoon belt, Sabah experience the worst Tropical Storm Greg on 25 December 1996.[216] The storm left more than 100 people dead, with another 200–300 missing, 3,000–4,000 people left homeless.[217][218] As Sabah also lies within the Sunda Plate with a compression from the Australian and Philippine Plate, it is prone to earthquake with the state itself have experienced three major earthquakes since 1923, with the 2015 earthquake being the latest major earthquake.[219] The Crocker Ranges together with Mount Kinabalu was formed since during the middle Miocene period after being uplifted by the Sabah Orogeny through compression.[220] There was some snow here in 1975 and 1993.[221]

- Landscapes of Sabah

-

Subsidiary peak of Mount Kinabalu

-

Lahad Datu District sea panoramic view

-

Padas River Valley

-

The northern tip of Borneo at Tanjung Simpang Mengayau facing both the South China Sea and Sulu Sea.

Biodiversity

The Semporna Peninsula on the north-eastern coast of Sabah is identified as a hotspot of high marine biodiversity importance in the Coral Triangle.[222]

The jungles of Sabah host a diverse array of plant and animal species. Most of Sabah's biodiversity is located in the forest reserve areas, which formed half of its total landmass of 7.34 million hectares.[223] Its forest reserve are part of the 20 million hectares equatorial rainforests demarcated under the "Heart of Borneo" initiative.[223] The forests surrounding the river valley of Kinabatangan River is the largest forest-covered floodplain in Malaysia.[224] The Crocker Range National Park is the largest national park in the state, covering an area of 139,919 hectares. Most of the park area are covered in dense forest and important as a water catchment area with its headwater connecting to five major rivers in the west coast area.[225] Kinabalu National Park was inscribed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2000 for its richness in plant diversity combined with its unique geological, topographical, and climatic conditions.[226] The park hosts more than 4,500 species of flora and fauna, including 326 bird and around 100 mammal species along with over 110 land snail species.[227][228]

Tiga Island is formed through the eruption of mud volcano in 1897. The island is now part of the Tiga Island National Park together with Kalampunian Besar and Kalampunian Damit islands as a tourist attractions,[229] with a mud bath tourism.[230] The Tunku Abdul Rahman National Park is a group of five islands of Gaya, Manukan, Mamutik, Sapi and Sulug. These islands are believed to once connected to the Crocker Range but separated when sea levels rose since the last ice age.[231] The Tun Mustapha Marine Park is the largest marine park located in the north of Sabah. It covers the three major islands of Banggi, Balambangan and Malawali.[232] Another marine park is the Tun Sakaran Marine Park located in the south-east of Sabah. The park comprising the islands of Bodgaya, Boheydulang, Sabangkat and Salakan along with sand cays of Maiga, Mantabuan and Sibuan. Bodgaya is gazetted as a forest reserve, while Boheydulang as a bird sanctuary.[233] These islands are formed by Quaternary pyroclastic material that was ejected during explosive volcanic activities.[234]

The Tawau Hills National Park established as a natural water catchment area. The park contains rugged volcanic landscapes including a hot spring and spectacular waterfalls. Bordering the Philippine Turtle Islands is the Turtle Islands National Park, it consists of three islands of Selingaan, Bakkungan Kechil and Gulisaan which is notable as the nesting place for green turtle and hawksbill sea turtle.[235] Other important wildlife regions in Sabah include the Maliau Basin, Danum Valley, Tabin, Imbak Canyon and Sepilok. These places are either designated as national parks, wildlife reserves, virgin jungle reserves, or protection forest reserve. Beyond the coasts of Sabah lie a number of islands rich with coral reefs such as Ligitan, Sipadan, Selingaan, Tiga and Layang-Layang (Swallow Reef). Other main islands including the Jambongan, Timbun Mata, Bum Bum and the divided Sebatik. The Sabah state government has enacted several laws to protect its forests and endangered wildlife species under the Animals Ordinance 1962,[236] Forest Enactment 1968[237] and the Wildlife Conservation Enactment 1997[238] among others.[239][240] Under the Wildlife Conservation Enactment, any persons hunting inside conservation lands are liable for imprisonment for five years and fined with RM50,000.[238] The state government also plans to implement seasonal huntings as part of its conservation efforts to prevent the continuous lose of its endangered wildlife species while maintaining the state indigenous hunting traditions.[241]

Conservation issues

Since the post-World War II timber boom driven by the need of raw materials from industrial countries, Sabah forests have been gradually eroded by uncontrolled timber exploitation and the conversion of Sabah forest lands into palm oil plantations.[243] Since 1970, forestry sector have contributed for over 50% of the state revenue, of which a study conducted in 1997 revealed the state had almost depleted all of its virgin forests outside the conservation areas.[242] The state government were determined to maintain the state biodiversity while to make sure the state economy continue to alive.[244] While in the same time facing hard task to control such activities although there is laws to prevent it.[240] The need for development and basic necessities also became an issue while to preserving the nature.[245][246] Mining activities had directly released pollutants of heavy metals into rivers, reservoirs, ponds and affecting groundwater through the leaching of mine tailings. An environmental report released in 1994 reported the presence of heavy metal at the Damit/Tuaran River that exceeded the water quality safe levels for consumption. The water in Liwagu River also reported the presence of heavy metal which was believed to be originated from the Mamut Mine.[247] Forest fire also have become the latest concern due to drought and fires set by irresponsible farmers or individuals such as what happened in the 2016 forest fires, where thousands of hectares of forest reserves in Binsuluk on the west coast of Sabah were lost.[248][249]

Rampant fish bombing has destroyed many coral reefs and affecting fisheries production in the state.[250][251] Moreover, the illegal activities of the extraction of river sand and gravel in the rivers of Padas, Papar and Tuaran had become the latest concern along with the wildlife and marine hunting and poaching.[247] Due to severe deforestation along with massive wildlife and marine poaching, the Sumatran rhino have been declared as extinct in early 2015.[252] Some other species that was threatened with extinction is banteng,[253] bearded pig,[254] clouded leopard, dugong,[255] elephant, false gharial, green turtle, hawksbill sea turtle, orangutan, pangolin,[256] proboscis monkey,[257] river shark,[258] roughnose stingray,[258] sambar deer, shark and sun bear.[254][259] Although the indigenous community are also involved in hunting, they hunt based on their spiritual believes and practice, and on a small scale, which differentiates them from poachers.[260] Well-known indigenous practices, such as "maganu totuo" or "montok kosukopan", "tuwa di powigian", "managal" or "tagal" and "meminting", have helped to maintain resources and prevent their depletion.[260]

Economy

Sabah GDP Share by Sector (2016)[261]

Sabah's economy is mainly based on primary sector such as agriculture, forestry and petroleum.[2][262] Currently, the tertiary sector plays an important part to the state economy, especially in tourism and services. With its richness in biodiversity, the state is offering ecotourism. Although in recent years the tourism industry has been affected by attacks and kidnapping of tourists by militant groups based in the southern Philippines, it remained stable with the increase of security in eastern Sabah and the Sulu Sea.[263] The tourism sector contribute 10% share of the state Gross domestic product (GDP) and was predicted to increase more.[264] Majority of the tourists come from China (60.3%), followed by South Korea (33.9%), Australia (16.3%) and Taiwan (8.3%).[265] Tourism plays a crucial role in the state's economy as the third largest income generating sectors with the state itself recorded a total of 3,879,413 tourist arrivals in 2018, a growth of 5.3% compared to 3,684,734 in 2017.[266] Since the 1950s, rubber and copra are the main source of agricultural economy of North Borneo.[267] The timber industry started to emerged in the 1960s due to high demand of raw materials from industrial countries. This was however replaced by petroleum in the 1970s after the discovery of oil in the area of west coast Sabah.[268] In the same year, cocoa and palm oil was added to the list.[262][269] The Sabah state government managed to increase the state fund from RM6 million to RM12 billion and poverty was down by almost half to 33.1% in 1980.[88] The state rapid development on primary sector has attracted those job seekers in neighbouring Indonesia and the Philippines as the state labour force itself are not sufficient.[270] The state GDP at the time ranked behind Selangor and Kuala Lumpur, being the third richest although the manufacturing sector remained small.[247][271] However, by 2000, the state started to become the poorest as it still dependent on natural resources as its primary sources of income comparing to those secondary sector producer states.[272] Thus the Sabah Development Corridor (SDC) was established in 2008 by Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi with a total investment of RM105 billion for 18 years to increase the state GDP to RM63.2 billion by 2025.[273] Around RM5.83 billion were allocated each year for infrastructures development along with the creation of 900,000 jobs.[273] The federal government targeted to eradicate hardcore poverty by the end Ninth Malaysia Plan (9MP) with overall poverty halved from 23% in 2004 to 12% in 2010 and 8.1% in 2012.[273] Since its establishment in 2008, the state GDP increase to 10.7% which was higher than the national economic growth of 4.8% and the world economic growth of 2.7%. Following the world financial crisis in 2009, Sabah GDP recorded 4.8% growth compared to −1.5% for national level and −0.4% for world level.[273]

From 2010 to 2011, the state experienced a slower growth due to weaker performance on the oil and gas sector. Based on 2014 survey, Sabah GDP recorded a 5.0% growth and remained as the largest contributor in agriculture sector with 18.1%, followed by Sarawak, Johor, Pahang and Perak. Its GDP per capita however are still lowest with RM19,672, the third lowest after Kelantan (RM11,815) and Kedah (RM17,321) from all 13 states.[274] In the same year, the state export value stood at RM45.3 billion with an import value of RM36.5 billion. Machinery and transportation equipment accounted for most of the imported products followed by fuel, mineral lubricants and others. While Sabah mostly exports raw petroleum and palm oil.[275] The state currently has a total of eight ports with two in Sepanggar while each one in Kota Kinabalu, Sandakan, Tawau, Kudat, Kunak and Lahad Datu that was operated and maintained by the Sabah Ports Authority owned by Suria Group.[276] As part of the Eleventh Malaysia Plan (11MP), the federal government has approved an allocation of RM800 million to expand the cargo handling of Sapangar Bay Container Port from 500,000 to 1.25 million TEUs per annum as well to accommodate larger ship like Panamax-size vessels.[277][278] An additional allocation of RM333.51 million was given in the same year, making it a total of RM1.13 billion with the project will start in 2017.[279][280] The fisheries industries remain the important part of Sabah primary sector economy with a contribution for about 200,000 metric tonnes of fish worth RM700 annually as well contributing 2.8% to the state annual GDP.[203] While the aquaculture and marine fish cage sector have produce 35,000 metric tons of brackish and fresh waters aquaculture and 360 metric ton of groupers, wrasses, snappers and lobsters worth around RM60 million and RM13 million respectively. Sabah is also one of the producer of seaweed, with most of the farms are located in the seas around Semporna.[203] Although recently the seaweed industry was heavily affected by spate of kidnappings perpetrated by the southern-Philippine-based Abu Sayyaf militant group.[281]

As of 2015, Sabah was producing 180,000 barrel of oil equivalent per day[282] and currently receives 5% oil royalty (percentage of oil production paid by the mining company to the lease owner) from Petronas over oil explorations in Sabah territorial waters based on the 1974 Petroleum Development Act.[88][283] Majority of the oil and gas deposits are located on Sabah Trough basin in the west coast side.[284] Sabah was also given a 10% stake in Petronas liquefied natural gas (LNG) in Bintulu, Sarawak.[285] Income inequality and the high cost living remain the major economic issues in Sabah.[286] The high cost living has been blamed on the Cabotage Policy, although the cause was due to the smaller trade volumes, cost of transport and efficiency of port to handle trade.[287] The government has set to review the Cabotage Policy even thought the cause was due to other reasons with the World Bank has stated that the result was due to weak distribution channels, high handling charges and inefficient inland transportation.[288] It was finally agreed to exempt the policy from 1 June 2017; with foreign ships will go directly to ports in the East without need to go to West Malaysia although Cabotage Policy on transshipment of goods within Sabah and Sarawak and the federal territory of Labuan remain.[289][290] Prime Minister Najib also promised to narrow development gap between Sabah and the Peninsular by improving and built more infrastructures in the state,[291] in which it was continued under the Pakatan Harapan (PH) administration where the new federal government also said the state should develop in par with Peninsular with the federal government will be consistent in commitment to helping develop the state as stated by Deputy Prime Minister Wan Azizah Wan Ismail.[292][293] Based on a latest record, the total unemployment in the state have been reduced from 5.1% (2014) to 4.7% (2015), although the number of unemployment was still high.[294] Slum is almost non-existent in Malaysia but due to the high number of refugees arriving from the troubling southern Philippines, Sabah has since seen a significant rise on its numbers. To eliminate water pollution and improve a better hygiene, the Sabah state government are working to relocate them into a better housing settlement.[295] As part of the BIMP-EAGA, Sabah also continued to position itself as a main gateway for regional investments. Foreign investment are mainly concentrated in the Kota Kinabalu Industrial Park (KKIP) areas.[283] Although country such as Japan have mainly focusing their various development and investment projects in the interior and islands since after the end of Second World War.[296] Following America's abandonment in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPPA) economic agreements in early 2017, Sabah began to turns its trade to China and India markets.[297] To further accelerate its economic growth, Sabah also targets several more countries as its main trade partners including Germany, South Korea, Thailand and the United Arab Emirates as the destinations of exports for food-based products, Brunei, Indonesia, Taiwan, the United States and New Zealand as the destinations for palm oil and logistics sector, Russia as the destination for the oil and gas industry and Japan and Vietnam as the destinations for the wood-based furniture industry.[298]

Infrastructure

Sabah's public infrastructure are still lagged behind mostly due to its geographical challenges as the second largest state in Malaysia.[5][299] The Sabah Ministry of Infrastructure Development (formerly known as Ministry of Communication and Works) is responsible for all public infrastructure planning and development in the state.[300] To narrow the development gap, the federal government are working to build more infrastructures and improve the already available one.[291] In 2013, Sabah state government allocates RM1.583 billion for infrastructure and public facilities development,[301] of which the state were allocated another RM4.07 billion by the federal government in 2015 Malaysian Budget.[302] Since the Eight Malaysia Plan (8MP) until 2014, a total of RM11.115 billion has been allocated for various infrastructure projects in the state.[303] Under the Tenth Malaysia Plan (10MP), infrastructure in the rural areas was given attention with the increase of rural water, electricity supply and road coverage.[304] Further large infrastructure allocation were delivered to both Sabah and Sarawak under the 2020 Malaysian Budget which include budget on improving connectivity and developing digital infrastructures for high speed internet in the rural areas.[305][306]

Energy and water resources

Electricity distribution in the state as well in the Federal Territory of Labuan are operated and managed by the Sabah Electricity Sdn. Bhd. (SESB). Sabah electrics are mostly generated from diesel power plant, hydropower and combined cycle power plants. The only main hydroelectric plant is the Tenom Pangi Dam.[299] The combined cycle power plant called Kimanis Power Plant was completed in 2014, supplying 300 MW, with 285 MW nominal capacity.[307] The plant is a joint venture between Petronas and NRG Consortium that also includes facilities such as gas pipeline of Sabah–Sarawak Gas Pipeline and a terminal of Sabah Oil and Gas Terminal.[307] There is another two combined cycle power plants with a capacity of 380 MW operated by Ranhill Holdings Berhad.[308] In 2009, the electricity coverage covers 67% of the state population and by 2011 increase to 80%.[299] The coverage reach 100% in 2012 after an allocation of RM962.5 million from the federal government were given to expand the coverage under the 2012 National Budget.[309] The electrical grid is divided into two of West Coast and East Coast which has been integrated since 2007.[299] The West Coast Grid supplies electricity to Kota Kinabalu, Papar, Beaufort, Keningau, Kota Belud, Kota Marudu, Kudat and Labuan with a capacity of 488.4 MW and maximum demand of 396.5 MW.[299] While the East Coast Grid supplies electricity to the major towns of Sandakan, Kinabatangan, Lahad Datu, Kunak, Semporna and Tawau with a capacity of 333.02 MW and maximum demand of 203.3 MW.[299]

In 2018, the federal government has announced that Sabah electrical grid will be upgraded to reduce power interruption.[310] Neighbouring Sarawak has also previously announced intention to provide additional electricity power to Sabah with full export will be finalised in 2021.[311][312] Electricity interconnection between Sabah, the Indonesian province of North Kalimantan and the Philippine province of Palawan as well for the whole Mindanao islands are also in the process as part of the BIMP-EAGA and Borneo-Mindanao power interconnection under the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Power Grid;[313][314][315] with the interconnection with Palawan is expected to be commenced in the nearest future.[316][317][318] Since 2007, there is an attempt to establish a coal power plant in Lahad Datu which receiving opposition from local residents and non-governmental organisations for the pollution that would be caused by the plant.[319][320] Thus Sabah has start to exploring alternative ways to generate electricity with the usage of renewable energy such as solar, mini hydro, biomass, geothermal and micro-algae and tidal technologies.[321][322] The Japanese government has extended aid totalling RM172,190.93 for the solar electrification project in the island of Larapan in Sabah's east coast in 2010.[323] In 2016, a research by United States GeothermEx Inc. and Jacobs New Zealand indicated the existence of an active geothermal system centred around the flanks of Mount Maria on Apas Kiri where it is suitable for Malaysia's first geothermal plant.[324] The construction for the first geothermal plant that expected to be completed in 2017 however was abandoned by the previous government in the mid-2016 with no sign of further progress.[325] A South Korean company GS Caltex also sets to build Malaysia's first bio-butanol plant in the state.[326]

Piped water supply in the state is managed by the Sabah State Water Department, an agency under the control of Sabah Ministry of Infrastructure Development. Operating with 73 water treatments plants, an average of 1.19 billion litres of water are distributed daily to meet Sabahan residents demands.[327] The coverage of water supply in major towns has reach 100% while in rural areas, the coverage still around 75% with total public pipes length up to 15,031 kilometres.[327] Some communities use gravity water systems.[328] The only water supply dam in the state is the Babagon Dam which holds 21,000 million litres of water.[329] To meet the increase demands, another dam named as Kaiduan Dam was being proposed to be built although being met with protest from local villagers who living on the proposed site.[330] Sabah has a natural gas demand of 9.9 million cubic metres (350 million cubic feet) per day at standard conditions in 2013, which increase to 14.8 million m3 (523 million cu ft) per day in 2015.[331] As Malaysia's liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) are much cheaper through the subsidy that was given by the federal government, it was found out in 2015 that around 20,000 LPG cylinders in Sabah east coast were smuggled by immigrants from neighbouring Indonesia and the southern Philippines in a monthly basis to their countries that leading to many Sabahans hard to retrieve enough supplies of LPG.[332] As a counter-measure, the Malaysian Ministry of Domestic Trade, Co-operatives and Consumerism (MDTCAC) has temporarily cancelled all permits to sell gas cylinders into neighbouring countries with a new policy will be implemented to control such illegal activities.[333][334]

Telecommunication and broadcasting

Telecommunication in Sabah and Sarawak were originally administered by Posts and Telecommunication Department until 1967,[335] and maintained by the British Cable & Wireless Communications before all telecommunications management in the state been takeover by Peninsular-based company.[336] The British telecommunication company have establish a submarine cable that linking Kota Kinabalu with Singapore and Hong Kong.[336] Following the expansion of the Peninsular-based company on 1 January 1968, Sabah Posts and Telecommunication Department was merged with the Peninsular telecommunication department to form Telecommunications Department Malaysia. All operations under Telecommunications Department Malaysia was then transferred to Syarikat Telekom Malaysia Berhad (STM) which become a public listed company in 1991 with the federal government retained a majority shareholding.[335] There are also other telecommunication companies operating in the state although only providing cellular phone facilities. In 2006, the state has the lowest Direct Exchange Line (DEL) penetration rate, with cellular and internet dial-up penetrations rate only 6.5 per 100 inhabitants.[299] Most residents from the low income groups would rather use mobile phones internet or use internet at their offices instead of setting up internet access at home due to the expensive cost and slow services.[299] Until the end of 2014, there were only 934 telecommunication hotspots in Sabah.[337] Due to this, the government are working to increase the penetration and capability of internet connection as well to bridge the gap between Sabah and the Peninsular.[338] From 2016, Unifi fibre optic coverage began to expand to other towns aside from the main city and major towns,[339] alongside Celcom and Maxis by the following year with a speed up to 100 Mbit/s.[340][341] In 2019, Digi launches its home fibre broadband in Sabah with speed up to 1 Gbit/s.[342] The mobile telecommunications in Sabah are mostly use 4G and 3G and there is also a free rural Wi-Fi services provided by the federal government known as the Kampung Tanpa Wayar 1Malaysia (KTW) although Malaysia's government-provided public internet speeds are among the slower than many other countries.[343][344]

The previous state internet traffic are routed through a hub in Malaysia's capital of Kuala Lumpur, passing through a submarine cable connecting the Peninsular with Kota Kinabalu. The systems are considered as costly and inefficient especially due to the price of leasing bandwidth with the large distance.[5] In 2000, there is a plan to establish Sabah own internet hub but the plan was unreachable due to the high cost and low usage rates in the state. Other alternative plan including using the Brunei internet gateway in a short term before establishing Sabah own gateway.[5] By 2016, the federal government has start to establish the first internet gateway for East Malaysia with the laying of 60 terabyte submarine cable which are developed by a private company named Xiddig Cellular Communications Sdn. Bhd. at a cost of about RM850 million through the Private Funding Initiative (PFI).[345] Under the 2015 Malaysian Budget project of 1Malaysia Cable System Project (SKR1M), a new submarine cable for high speed internet has been built from Kota Kinabalu to Pahang in the Peninsular which completed in 2017.[346][347] The 1Malaysia submarine cable system linking the state capital with Miri, Bintulu and Kuching in Sarawak together with Mersing in Johor with an increase of bandwidth capacity up to 12 terabyte per second.[348] Another submarine cable, the BIMP-EAGA Submarine and Terrestrial (BEST) Cable Project is currently being built from Kota Kinabalu to Tawau to connecting Sabah with Brunei, Kalimantan and Mindanao which will be completed in 2018.[349] In early 2016, a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed between the state government and China's largest networking company, Huawei to set Sabah to become information and communications technology (ICT) hub by leveraging on Huawei's ICT expertise.[350] More free high speed Wi-Fi hotspots are being planned in Sabah, especially to the state capital.[351]

Sabah launched its radio service on 9 November 1955, which became a part of Radio Malaysia when it joined Malaysia in 1963 and later part of the bigger Radio Televisyen Malaysia (RTM) in 1969, when the nation's radio and television operations merged.[352] On 28 December 1971, RTM launched a third TV station solely for Sabah. But following the construction of earth satellite station near Kuantan, Pahang and Kinarut for communications and television broadcast via the Indian Ocean Intelsat III satellite and the introduction of TV1 on 30 August 1975 and TV2 on 31 August 1983 in the state, it ceased to air by mid-1985. RTM has four branches in the state - a main office in capital city Kota Kinabalu and three other offices in Keningau, Sandakan and Tawau. The main office produces news and shows for RTM's television channels and operates two state radio channels, namely Sabah FM and Sabah V FM, whereas three other offices operate district radio channels such as Keningau FM, Sandakan FM and Tawau FM.

Other radio channels in the state include KK FM which is operated by Universiti Malaysia Sabah,[353] and Bayu FM which is only available through Astro, the Malaysian main satellite television.[354] Several newly independent radio station have recently been launched in the state, namely Kupi-Kupi FM in 2016,[355] KK12FM and VOKFM in 2017.[356][357] Other Peninsular-based radio stations also had set up their offices in the state to tap the emerging market. Sabahan DJs are mostly hired and local state songs will be played to meet Sabahan listeners taste and slang. Television broadcasting in the state is divided into terrestrial and satellite television. As Malaysia aims for digital television transition, all analogue signal will be shut down soon.[358] There are two types of free-to-air television provider such as MYTV Broadcasting (digital terrestrial) and Astro NJOI (satellite). On the other hand, IPTV is available via the Unifi TV through Unifi fibre optic internet subscription.[359] The state first established newspaper is the Sabah Times (rebranded as the New Sabah Times), founded by Fuad Stephens, who became the first Chief Minister of Sabah.[360] Other main newspapers include the independent Daily Express,[361] Overseas Chinese Daily News,[362] the Sarawak-based The Borneo Post,[363] the Peninsular-based Sin Chew Daily[364] and the Brunei-based Borneo Bulletin.[365]

Transportation

Sabah has a total of 21,934 kilometres (13,629 mi) road network in 2016, of which 11,355 kilometres (7,056 mi) are sealed road.[366] Before the formation of Malaysia, the state together with Sarawak only has rudimentary road systems.[367] Most trunk roads was then constructed from the 1970s until the 1980s under the World Bank loans. In 2005, 61% of road coverage in the state were still gravel and unpaved, comprising 1,428 kilometres (887 mi) federal roads and 14,249 kilometres (8,854 mi) state roads, of which 6,094 kilometres (3,787 mi) are sealed while the remaining 9,583 kilometres (5,955 mi) were gravel and unpaved roads.[299] This led to great disparity between roads in the state with those in the Peninsular, with only 38.9% are sealed while 89.4% have been sealed in the Peninsular. Due to this, SDC was implemented to expand the road coverage in Sabah along with the construction of Pan-Borneo Highway. Since the 9MP, various road projects has been undertaken under the SDC and around RM50 million has been spent to repairs Sabah main roads since the 8MP.[299] The high cost to repair roads frequently has led the Sabah state government to find other alternative ways to connecting every major districts by tunnelling roads through highlands which will also saving time and fuel as the distance being shortened as well to bypass landslides.[368][369] In early 2016, the expansion project of Pan-Borneo Highway has been launched to expand the road size from single carriageway to four-lane road, while city highway been expand from four-lane to eight-lane as well with the construction of new routes which will connect the state with Sarawak, Brunei and the Trans Kalimantan Highway in Indonesia.[370][371] The project is divided into two packages: the first package covering the West Coast area will complete in 2021, while the second covering the East Coast area will finish in 2022.[372][373][374] All state roads are maintained under the state's Public Works Department,[375] while federal roads maintained by the national Public Works Department.[376]