Nicole Brown Simpson

Nicole Brown Simpson | |

|---|---|

Brown in 1993 | |

| Born | Nicole Brown May 19, 1959 |

| Died | June 12, 1994 (aged 35) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Murder by knife wounds[1] |

| Resting place | Ascension Cemetery, Lake Forest, California 33°39′04″N 117°41′37″W / 33.6512°N 117.6935°W |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

Nicole Brown Simpson (née Brown; May 19, 1959 – June 12, 1994) was the second wife of American professional football player, actor, and media personality O. J. Simpson. She was murdered outside her Brentwood home, along with her friend Ron Goldman, in 1994.

Brown met Simpson in 1977 and they married in 1985, five years after Simpson had retired from professional American football. Their marriage lasted eight years and they had a daughter and a son. Reports suggest that Simpson emotionally, verbally, and physically abused Brown throughout their relationship, which continued after their divorce. Brown and Simpson made an attempt at reconciliation, but later broke up again, seemingly permanently, in May 1994.

In June 1994, Brown and Goldman were stabbed to death, and Simpson was tried for the murders. Following a highly publicized criminal trial, Simpson was acquitted of all charges, though he was later found liable of the wrongful deaths in a civil lawsuit in 1997. No other suspects have ever been identified, and the killings remain unsolved, although Brown's family have expressed the belief that Simpson committed the murders and was the sole perpetrator.

Early life

[edit]Nicole Brown was born on May 19, 1959, in Frankfurt, West Germany,[2][3] to Juditha Anne "Judy" Brown (née Baur) and Louis Hezekiah "Lou" Brown Jr.[4][5] Her mother was German, and her father American.[3][6] She was the second of four daughters (Denise, Dominique and Tanya being the other three).[7] From her father's previous marriage, she also had two older half-sisters (Wendy and Margit) and one older half-brother (Tracy).[8] After moving to the United States, she attended Rancho Alamitos High School in Garden Grove, California.[9] She graduated from Dana Hills High School, in Dana Point, California, in 1976.[10] She was raised Catholic.[11]

In Brown's 1976 senior yearbook from Dana Hills High School, her nickname is "nick" and her quote is that she: "remembers Jr. Sr. prom, kissing a pumpkin at the homecoming dance '74, one of the semi-finalists for Homecoming, plans to ski Europe, go to Brooks photo school, get Scott, 'Be yourself, don't be phony, you don't have to do anything.'"[12] Brown's mention of "Brooks photo school" was referring to The Brooks Institute of Photography that operated from 1945 to 2016 in the Santa Barbara, California area, a two-hour drive from her high school.

Relationship with O. J. Simpson

[edit]Early relationship

[edit]Brown met American professional football player, actor, and media personality O. J. Simpson in 1977,[13] when he was 30 and she was 18. At the time she was working as a waitress at The Daisy, a Beverly Hills nightclub.[14][15][16][17] They began dating while Simpson was still married to his first wife, Marguerite Whitley, who was then pregnant with their daughter Aaren. Simpson and Whitley divorced in March 1979.[18]

In the June 3, 2024 issue of People, Brown's older sister Denise revealed that Simpson was at times hostile to Nicole even during the early days of their relationship, including on one occasion in 1977 after she and her family went to upstate New York to attend a Buffalo Bills game which Simpson was playing in.[19] According to Denise, Simpson "flipped out" during this occasion after seeing Nicole kiss a mutual male friend on the cheek and "had her in the upstairs bathroom crying. He said, ‘You embarrassed me.’ "[19]

Brown had a non-speaking acting part as "Passenger on Bus" in the 1980 TV film Detour to Terror, executive produced by Simpson who starred in the film.[20] During the 1984 Summer Olympics torch relay, Simpson carried the torch on Santa Monica's California Incline road, running behind Brown.[21] Simpson was among the many celebrities who attended the premiere of the Michael Jackson short film Captain EO in 1986, which Brown also attended.[22]

Marriage

[edit]

Brown and Simpson were married on February 2, 1985, five years after his retirement from professional football.[23] The couple had two children, Sydney Brooke Simpson (b. 1985) and Justin Ryan Simpson (b. 1988),[24] both delivered via caesarian section.[25] Additionally, she had three abortions[26] (one outside of wedlock).[27] The marriage lasted seven years.[28] According to Denise Brown, Nicole considered becoming a mom to be a crowning achievement, though Simpson became more volatile towards her afterwards.[19]

According to Sheila Weller, "[Simpson and Brown] were a dramatic, fractious, mutually obsessed couple before they married, after they married, after they divorced in 1992, and after they reconciled."[29]

Domestic violence

[edit]According to multiple accounts, Simpson emotionally, verbally, and physically abused Brown throughout their relationship, which continued after their divorce. According to Brown's sister Dominique, Simpson referred to her as a "fat pig" during a pregnancy.[19] During an incident on New Year's Day 1989, a police report indicated Simpson said: "I don't want that woman [Brown] sleeping in my bed anymore! I got two women, and I don't want that woman in my bed anymore."[3] A family friend claimed that Simpson had told Brown's friends that if he ever "caught her with anyone, he would kill her".[30]

On December 31, Brown phoned the police, saying that she thought Simpson was going to kill her. She was found by officers hiding in the bushes outside their home, "badly beaten and half-naked". Authorities said Simpson had "punched, slapped, and kicked" her. Simpson sped away from the cops in his car, but eventually, he pleaded no contest to spousal abuse.[28][30] Brown dropped the charges after her parents allegedly encouraged her to reconcile with Simpson, who was enabling her father, Louis, to invest in a lucrative Hertz car rental facility at The Ritz Carlton at Monarch Bay, California, which significantly benefited the Brown family financially.[31]

In addition to the physical abuse, Simpson was also reported to have been an avid womanizer who engaged in numerous infidelities while married to Brown.[32] In the 2016 documentary O.J.: Made in America, Simpson and Brown's old Brentwood friend Robin Greer said that Simpson and Brown constantly fought over his affairs with other women.[32] Greer even noted how Simpson made repeated advances towards her as well.[32] At the time of their separation, Simpson informed Brown of his ongoing one-year extramarital affair with Tawny Kitaen.[33] The affair was revealed at Simpson's 1997 civil trial for wrongful death.[34][35]

A family friend claimed that Simpson had told Brown's friends that if he ever "caught her with anyone, he would kill her." Brown's friend Kris Jenner claimed Brown at one point told her, "Things are really bad between O.J. and I, and he's going to kill me, and he's going to get away with it."[36] The two broke up again, seemingly permanently, in May 1994.[37] In total, prosecutors for Simpson's murder trial found 62 incidents of abusive behavior by Simpson towards Brown. News reporting regarding these incidents led to California enforcing its 1986 laws protecting domestic violence victims more. Hertz continued to air its commercials with Simpson until they cut all ties to him amid the murder trial.[38][39]

Among the more caustic accounts, Bethy Vaquerano, a maid to Brown, in a letter outlined in American Tragedy: The Uncensored Story of the Simpson Defense, described Brown as being abusive towards Simpson and that Brown was racist and antisemitic.[40] Some sources claimed that Brown was determined to keep her children's biracial identity as much of a nonissue as possible and that she, and Simpson's friend, Tom McCollum, called Simpson "Largehead," Brown using the word in a condescending manner.[41] Jennifer Young (the daughter of realtor Elaine Young who sold Simpson the Rockingham house) and Victoria Sellars also claimed that Brown pulled up once while they were with Simpson and that Brown accused him of angrily cheating on her. Young said Simpson remained calm throughout the incident.[42] Jennifer Peace said that Simpson's close friend Al Cowlings described loud fights between Simpson and Brown and that Brown would berate her husband with racial slurs.[43]

Divorce

[edit]In January 1992, Brown moved into a rental home in Brentwood, a neighborhood in Los Angeles, California – a 4-bedroom, Tudor-style house with 3,400 square feet on Gretna Green Way where she lived for 2 years.[44]

Simpson filed for divorce on February 25, 1992, citing irreconcilable differences.[45] They then shared custody of their children Sydney Brooke (age 7) and Justin Ryan (age 4).

Ongoing relationship and abuse

[edit]Reports suggest that in 1993, after the divorce, Brown and Simpson made an attempt at reconciliation.[30] During this time Simpson continued his abuse of Brown.[46] Brown told her mother after the divorce that Simpson was following her, stating, "I go to the gas station, he’s there. I go to the Payless shoe store, and he’s there. I’m driving, and he’s behind me.'"[47]

On October 25, 1993, Brown called the police to report Simpson being violent again, after he allegedly found a photo of a man Brown had dated while they were broken up. Brown called 911, crying and saying that Simpson was "going to beat the shit out of me".[48] Simpson angrily shouted in the background, "You did not give a shit about the kids when you were (having sex with him) in the living room! They were here! Didn't care about the kids then!"[49] Simpson also expressed frustration regarding Brown surrounding herself with and exposing her children to frequent drug users, prostitutes and drug dealers. Several times, Simpson expressed disappointment in the dangerous choices Brown had made and concern for his children. Simpson repeatedly said, "I’m leaving with my two fucking kids is when I’m leaving."[50]

When the police arrived, Brown was secretly recorded by Sgt. Craig Lally. "He gets a very animalistic look in him," Brown stated. "All his veins pop out, his eyes are black and just black, I mean cold, like an animal. I mean very, very weird. And when I see it, it just scares me." Brown also stated Simpson had not hit her in four years, referring to the January 1, 1989 incident as the last time Simpson had become physical with her.[51]

Several months after this incident, Brown moved out of their shared home and the relationship ended.[48]

Post-divorce life

[edit]Brown met and became friends with Kato Kaelin on a skiing trip in Aspen, Colorado, in December 1992. He later moved into the guest house on Brown's property on Gretna Green Way and lived there for a year. He paid rent and helped take care of Sydney and Justin as part of the living arrangement.[52] She also entertained other suitors, including restaurateur Keith Zlomsowitch and Marcus Allen.[53][54][55] Despite speculation of her having been a recreational drug user during this time, there is no solid evidence of Nicole Brown Simpson using drugs; she had no drugs in her system at the time of her death and her house was clear of paraphernalia.[56][57]

Brown and Faye Resnick first met in 1990. According to Robert Kardashian, Resnick only knew Brown for a year and a half. The two socialized in and around Brentwood, Los Angeles and vacationed in Mexico together.[58][59] Resnick's third husband, Paul, reported that a concerned Brown called him in early June 1994 to report that "Faye was getting out of control" and abusing cocaine again. Resnick stayed for several days at Brown's condominium until on June 9, 1994, Brown and several other friends conducted an intervention and persuaded Resnick to check into the Exodus Recovery Center in Marina Del Rey, California.[58]

In January 1994, Brown moved just a few minutes away from her Gretna Green house to a three-story, rental townhome on Bundy Drive in Brentwood. It was a Mediterranean-style residence that was 3,400 square feet with multiple patios and a "rooftop sundeck."[60] In Brown's Brentwood neighborhood, situated near the base of the Santa Monica mountains and four miles from the ocean, were country clubs, local and state parks, hiking trails, and popular attractions like the Santa Monica Pier. At the time she drove a Ferrari[61] - which she would later lend to Ron Goldman whom she had met some six weeks prior to their deaths. The upscale area had shops, restaurants, and grocery markets near her home. Brown's sister Denise described this period in a 1994 interview, saying that Nicole "was just so vivacious, so full of life" and "I was so happy for her. For the first time in her life, she was able to have her own friends. We were talking about going to Yosemite, camping, taking the kids to Club Med. Everything was going to revolve around the kids."[62]

Death

[edit]Final days

[edit]

On March 16, 1994, Brown and her children attended the premiere for Simpson's newest film, Naked Gun 33⅓: The Final Insult.[63] According to Brown's close friends, Simpson stalked Brown and initiated a reconciliation attempt in 1993. He repeatedly begged her to come back to him, and sent her a letter apologizing, sending her their wedding video.

Brown met 25-year-old restaurant waiter Ron Goldman six weeks prior to their deaths. According to police and friends, they had a platonic relationship, occasionally meeting for coffee and dinner. Goldman borrowed her Ferrari when he met a friend for lunch. The friend, Craig Clark, stated that Goldman told him it was his friend Nicole's car.[64]

Brown developed pneumonia in May and Simpson came to her house to care for her.[65] Simpson left for Palm Springs Memorial Day weekend 1994.[66] Just one day before the murders, Brown and her close friend Kris Jenner spoke on the phone, making plans to go to lunch the next day.[67] Kris said in an interview that Nicole wanted to confide in her about something "very important" and possibly reveal information about her "volatile" relationship with Simpson, but Brown was murdered before they could meet.[67]

June 12, 1994

[edit]

At the time of her death, Brown resided at 875 South Bundy Drive in Brentwood, Los Angeles, California, with her two children.[68][69][70] On the evening of June 12, Brown took Sydney and a friend out to dinner after the children's dance recital.[61] The defense team would cite that Brown had an intense argument on the phone, overheard by eight-year-old Sydney upstairs,[71] and that a witness named Tom Lang saw Brown arguing with two men in the area of the sidewalk near the front of her house shortly after 10:00 that night.[72] Brown's mother, Juditha, told police and investigators in a sworn statement that she was speaking with her daughter on the telephone at 11:00pm that night.[73] Those phone records were sealed.

Brown and Goldman were stabbed to death outside her home; their bodies were found shortly after midnight. Brown was lying in the fetal position in a pool of blood.[74] An autopsy determined that she had been stabbed seven times in the neck and scalp and had sustained a 14 cm-long (5.5 inches) gash across her throat, which had severed both her left and right carotid arteries and breached her right and left jugular veins.[74] The wound on Brown's neck penetrated 1.9 cm (0.75 inches) into her cervical vertebrae,[74] nearly decapitating her.[48][75] She also had defensive wounds on her hands.[74]

During a reconstruction of events, the police theorized that Brown and Goldman were talking on the front patio of Brown's condominium when they were attacked or that Goldman arrived while Brown was being attacked; in any case, the police believe that Brown was the intended target and that Goldman was killed in order to silence him.[76] Witness Robert Heidstra testified that while walking near Brown's condominium that night, he heard a man yelling, "Hey! Hey! Hey!" who was then shouted at by a second man. He also heard a gate slam.[77] Goldman's family came to believe that Goldman was the man shouting "Hey!" and that he may have attempted to save Brown by intervening in the attack.[78][79]

Brown's funeral was held on June 16 at the St. Martin of Tours Catholic Church in Brentwood,[80] with mourners including Simpson and their two children,[81] members of Brown's family, Al Cowlings, Kato Kaelin, and Steve Garvey.[82] Brown is buried in Ascension Cemetery[83] in Lake Forest, California.[84] On June 22, Brown's sister, Denise was quoted by the New York Times that she did not think of her sister as a battered woman, even after Simpson was charged with assault on New Year's Eve 1989.[85]

Trials

[edit]Criminal trial

[edit]

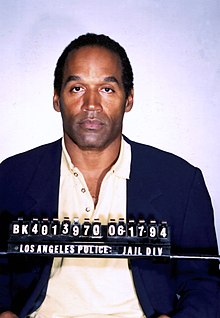

After leading police on a low-speed chase in a now infamous white Ford Bronco, Simpson was tried for the murders of Brown and Goldman. The trial spanned eight months, from January 24 to October 3, 1995, and received international publicity and exacerbated racial divisions in the U.S. During the trial, there was some speculation as to whether Brown and Goldman were secretly dating, compounded by three facts, that Brown was wearing a slinky, revealing cocktail dress when she was found dead, candles were lit in the master bedroom and bathroom, and the master bathroom’s tub was full of water.[86]

Though prosecutors argued that Simpson was implicated by a significant amount of forensic evidence, he was acquitted of both murders on October 3.[87][88][89][90] Commentators agree that to convince the jury to acquit Simpson, the defense capitalized on anger among the city's African-American community toward the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), which had a history of racial bias and had inflamed racial tensions in the beating of Rodney King and subsequent riots two years prior.[91][92][93] The trial is often characterized as the trial of the century because of its international publicity and has been described as the "most publicized" criminal trial in history.[94] Simpson was formally charged with the murders on June 17; when he did not turn himself in at the agreed time, he became the subject of a police pursuit.[95] TV stations interrupted coverage of the 1994 NBA Finals to broadcast live coverage of the pursuit, which was watched by around 95 million people.[96] The pursuit and Simpson's arrest were among the most widely publicized events in history.

Simpson was represented by a high-profile defense team, referred to as the "Dream Team", initially led by Robert Shapiro[97][98] and subsequently directed by Johnnie Cochran. The team included F. Lee Bailey, Alan Dershowitz, Robert Kardashian, Shawn Holley, Carl E. Douglas, and Gerald Uelmen. Simpson was also instrumental in his own defense. While Deputy District Attorneys Marcia Clark, William Hodgman, and Christopher Darden believed they had a strong case, the defense team persuaded the jury there was reasonable doubt concerning the DNA evidence.[87] They contended the blood sample had been mishandled by lab scientists[99] and that the case had been tainted by LAPD misconduct related to racism and incompetence. The use of DNA evidence in trials was relatively new, and many laypersons did not understand how to evaluate it. The defense retained renowned advocate for victims of domestic abuse Lenore E. Walker.[100] Cochran said that she would testify that Simpson does not fit the profile of an abuser that would murder his spouse; "He has good control over his impulses. He appears to control his emotions well."[101] Brown's friend, Cora Fischman, testified that Brown never said anything to her about being abused by Simpson during the months leading up to the murders.[102]

The trial was considered significant for the wide division in reaction to the verdict.[103] Observers' opinions of the verdict were largely related to their ethnicity; the media dubbed this the "racial gap".[104] A poll of Los Angeles County residents showed most African Americans thought the "not guilty" verdict was justified while most whites thought it was a racially motivated jury nullification[105][106] by the mostly African-American jury.[107] Polling in later years showed the gap had narrowed since the trial; more than half of polled Black respondents expressed the belief that Simpson was guilty.[108] In 2017, three jurors who acquitted Simpson said they would still vote to acquit, while one said he would convict.[109]

In the 1996 book Killing Time: The First Full Investigation into the Unsolved Murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman, authors Donald Freed and Raymond P. Briggs wrote that lipstick was found on Goldman's cheek after his death, and suggested that Brown kissed Goldman when he arrived and that they were together on the front porch when they were attacked.[110]

Civil trial

[edit]In 1996, Fred Goldman and Sharon Rufo, the parents of Ron Goldman, and Lou Brown, father of Nicole Brown filed a civil suit against Simpson for wrongful death.[111] Presiding Judge Hiroshi Fujisaki did not allow the trial to be televised, did not sequester the jury, and prohibited the defense from alleging racism by the LAPD and from condemning the crime lab.[112] The physical evidence did not change but additional evidence of domestic violence was presented as well as 31 pre-1994 photos of Simpson wearing Bruno Magli shoes,[113] including one that was published 6 months before the murders, proving it could not be a forgery.[114]

One significant difference between the two trials was the admission of Brown's diary entries in the civil case. Lead counsel Daniel Petrocelli explained, "The least explored aspect of the case is Simpson's motive. You cannot just say this murder was a culmination of domestic-violence incidents. You need to tell the jury a story. This was about a stormy relationship." Time magazine reported, "That strategy made the difference in understanding Simpson... Nicole's diary showed that she and Simpson were having fights in those last weeks. Their hostilities had taken a cruel turn. Simpson sent Nicole a letter that was a thinly veiled threat to report her to the IRS for failing to pay capital-gains taxes. Infuriated, she started to deny him access to the children.... She began to treat him like a stranger. That, Petrocelli said, is when three weeks of retaliation began In that period, the lawyer argued, Simpson grew angrier and more obsessed with his ex-wife, developing a rage that resulted in death for her and Ron Goldman."[115]

The civil judge found the diary entries were admissible because they were pertinent to Nicole's state of mind, which in turn was relevant to Simpson's motive[116]—reversing a crucial ruling from the criminal case that excluded the diary as "inadmissible hearsay".[117] The civil court's ruling was upheld on appeal.[118] The jury found Simpson liable for the murders and awarded the victims' families $33.5 million in compensatory and punitive damages.[119] Simpson filed for bankruptcy afterwards and relocated to Florida to protect his pension from seizure. His remaining assets were seized and auctioned off with most being purchased by critics of the verdict of the criminal trial to help the plaintiffs recoup the costs of litigation. Simpson's Heisman Trophy was sold for $255,500 to an undisclosed buyer. All the proceeds went to the Goldman family, who said they have received only one percent of the money that Simpson owes from the wrongful death suit.[120][121]

Following Simpson's acquittal, no additional arrests or convictions related to the murders were made. He maintained his innocence in subsequent media interviews. Simpson was subsequently jailed for an unrelated armed robbery at a Las Vegas hotel in 2008.[122][123] Following Simpson's death in 2024,[124] Simpson estate lawyer Malcolm LeVergne pledged to prevent the Brown and Goldman families from obtaining the money which was promised in the civil trial judgement, but later reversed course.[125]

Custody of children

[edit]In 1996, after the conclusion of the criminal trial, a judge granted Simpson's petition to give him full custody of Sydney and Justin.[126] Brown's parents continued unsuccessfully to fight for custody[127][128][129] until 2006, when Justin turned 18 and legally became an adult. Sydney turned 18 in 2003.

Alternate theories and suspects

[edit]While defence attorney F. Lee Bailey and several members of Simpson's family still advocated for Simpson's innocence,[130][131] such theories have been rejected by prosecutors, witnesses and the families of Brown and Goldman, who have expressed the belief that Simpson committed the murders and was the sole perpetrator.[132][133][134] Alternative theories have been suggested, such as that Simpson may have had accomplices in the murders, or that he was not involved at all and was framed. Several speculate that the murders were related to the Los Angeles drug trade and the murders of Michael Nigg and Brett Cantor.[135][136][137][138][139][140][141]

The 2000 BBC TV documentary O.J.: The True Untold Story,[142] primarily rehashes the contamination and blood planting claims from the trial and asserted that Simpson's elder son Jason is a possible suspect, due to - among other reasons - Simpson hiring defense attorneys for his children first before himself, pictures of Jason's descriptive wool cap, and an alleged prior arrangement to meet with Brown that evening.[143][144][145] William Dear published his findings in the book O.J. Is Innocent and I Can Prove It.[146]

A 2012 documentary entitled My Brother the Serial Killer examined the crimes of convicted murderer Glen Edward Rogers and included claims that Rogers had killed Brown and Goldman in California in 1994.[147][148][149][150] According to Rogers' brother Clay, Rogers claimed that, before the murders, he had met Brown and was "going to take her down."[150] During a lengthy correspondence that began in 2009 between Rogers and criminal profiler Anthony Meoli, Rogers wrote and created paintings about his involvement with the murders. During a prison meeting between the two, Rogers claimed Simpson hired him to break into Brown' house and steal some expensive jewellery. He said that Simpson had told him, "You may have to kill the bitch". In a filmed interview, Rogers' brother Clay asserts that his brother confessed his involvement.[150] Rogers' family stated that he had informed them that he had been working for Brown in 1994 and that he had made verbal threats about her to them. Rogers later spoke to a criminal profiler about the murders, providing details about the crime and remarking that he had been hired by Simpson to steal a pair of earrings and potentially murder Brown.[citation needed] LAPD responded to the documentary as follows: “We know who killed Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman. We have no reason to believe that Mr. Rogers was involved.” Fred Goldman, father of Ron Goldman stated: “The overwhelming evidence at the criminal trial proved that one, and only one, person murdered Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman. That person is O.J. Simpson and not Glen Rogers.”[151]

Legacy

[edit]Foundation

[edit]The Nicole Brown Simpson Foundation was established in 1994 in her memory.[152] Later renamed the Nicole Brown Charitable Foundation, it reportedly cut back on grantmaking in 1999 due to a drop in donations and questionable management practices.[153][154]

Tributes

[edit]In a rare 1996 VHS video by her parents called A Tribute to Nicole, she is described as having had a "happy childhood" growing up in a "close family" and as "lov[ing] interior decorating."[155] Clips from the family's home movies show her as a young girl playing with stuffed animals, swimming in a pool, dancing, carrying school books, and blowing out birthday candles on cupcakes. Her mother called Nicole "warm", "wonderful", and "free-spirited".[155]

Kato Kaelin described Brown in a 2024 interview as a "beautiful" friend who was a "beacon of light, always bright, always fun".[156] Kris Jenner said Brown was "one of [her] best friends"[157] with whom she often took family vacations.[158] Jenner also shared memories of a Los Angeles restaurant she used to frequent with Brown and their mutual friend, Faye Resnick.[159]

Brown's sister, Tanya Brown, said in a 2019 interview that "Nicole was a mom: she put her kids first, she put everybody else first. My sister had the ability to live life, live it bright, live it large."[160] That same year, Tanya wrote an article claiming that she had forgiven Simpson, despite believing him responsible for her sister's murder.[161]

Kris Jenner named her fourth daughter, Kendall Nicole Jenner, after Brown.[158] Kendall was born 17 months after Brown's death.

When filmmaker Ezra Edelman, director of the documentary O.J.: Made in America, won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature, he dedicated the award to both Brown and Goldman in his acceptance speech.

Death of parents

[edit]On July 3, 2014, Brown's father, Louis Hezekiah "Lou" Brown Jr., died aged 90. He was interred next to Nicole in Ascension Cemetery in Lake Forest, California. Nicole's headstone (which had space on the headstone for an additional inscription) was altered to include her father.[162]

On November 8, 2020, Brown's mother, Juditha Anne "Judi" Baur Brown, died aged 89. She was interred in Ascension Cemetery next to her husband and daughter. Nicole's original headstone was replaced by a larger one that included the inscriptions for both of her parents on it.[163]

Property

[edit]Two years after the deaths of Brown and Goldman, the townhouse at 875 South Bundy Drive[68][69][70] was extensively remodeled by a new owner, who also had the address changed.[164]

Media

[edit]Book

[edit]"Nicole. Jesus. I looked down and saw her on the ground in front of me, curled up in a fetal position at the base of the stairs, not moving. Goldman was only a few feet away, slumped against the bars of the fence. He wasn't moving either. Both he and Nicole were lying in giant pools of blood. I had never seen so much blood in my life. It didn't seem real, and none of it computed."

Simpson wrote a book, If I Did It, a first-person account of how he would have committed the murders if he had committed them. In Simpson's hypothetical scenario, he has an unwilling accomplice named "Charlie" who urges him to not engage with Brown, whom Simpson plans to "scare the shit out of".[165] Simpson ignores Charlie's advice and continues to Brown's condo, where he finds and confronts Ron Goldman. According to the book, Brown falls and hits her head on the concrete, and Goldman crouches in a karate pose. As the confrontation escalates, Simpson writes, "Then something went horribly wrong, and I know what happened, but I can't tell you how."[166] He writes that he regained consciousness later with no memory of the actual act of murder.[165]

Simpson's eldest daughter, Arnelle Simpson, testified in a deposition that she and Van Exel, president of Raffles Entertainment and Music Production, came up with the idea for the book and pitched it to her father in an attempt to make money.[167] She testified that her father thought about it and eventually agreed to the book deal.[167] Simpson stated, "I have nothing to confess. This was an opportunity for my kids to get their financial legacy. My kids understand. I made it clear that it's blood money, but it's no different than any of the other writers who did books on this case."[167]

According to court documents, in August 2007, as part of the multi-million dollar civil jury award against Simpson to ensure he would not be able to profit from the book, the Goldman family were granted the proceeds from the book. The Goldman family still own the copyright, media rights, and movie rights[168] and have acquired Simpson's name, likeness, life story, and right of publicity in connection with the book. After renaming the book If I Did It: Confessions of the Killer, the Goldman family published it in September 2007 through Beaufort Books.[169] Denise Brown, Nicole Brown's sister, criticized the Goldmans for publishing the book and accused them of profiting from Brown and Goldman's deaths.[170]

Portrayals

[edit]Brown was portrayed by Jessica Tuck in the 1995 television movie The O. J. Simpson Story,[171] by Kelly Dowdle in the 2016 Netflix series The People v. O. J. Simpson: American Crime Story,[172] by Mena Suvari in the 2019 film The Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson,[173] and by Charlotte Kirk in the upcoming 2025 film The Juice.[174]

Documentary

[edit]Upon Simpson's death in 2024, Lifetime announced a two-part documentary about Brown was in development titled The Life and Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson, which aired on June 1 and 2, 2024.[175]

See also

[edit]- Domestic violence in the United States

- Violence Against Women Act

- List of unsolved murders (1980–1999)

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Turvey, Brent E. (February 1995). "An Overview of the Medicolegal Evidence Regarding: The State of California v. Orenthal James Simpson, Case: BA097211" Archived August 4, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Knowledge Solutions.

- ^ Schmalleger 1996, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Hubler, Shawn; Trounson, Rebecca (July 3, 1994). "Dreams of Better Days Died That Night". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Schindehette, Susan (August 1994). "To Live and Die in L.A." People. Vol. 42, no. 5. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Gates, Anita (July 6, 2014). "Louis Brown Jr., Nicole Simpson's Father, Dies at 90". The New York Times. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Weller 1995, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Finn, Natalie (June 12, 2019). "Inside the Short, Tragic Life of Nicole Brown Simpson and Her Hopeful Final Days". eonline. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ Weller 1995, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Weller 1995, pp. 84, 122.

- ^ "Classmates - Dana Hills High School Yearbook 1976". secure.classmates.com. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ "The O.J. Simpson Trial: Nicole Brown Simpson Part 1". Listen Notes (Transcript). October 3, 2019. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

She's [Nicole] an outdoor girl. And she's also raised Catholic because her mom is Catholic...

- ^ Dana Hills High School Yearbook (1976). p. 161. Worthpoint.com. https://thumbs.worthpoint.com/zoom/images4/1/1215/19/nicole-brown-simpson-high-school_1_e86f03c852af254e94a3e755bd97c708.jpg}

- ^ Bugliosi 1997, p. 175; Weller 1995, pp. 6, 123.

- ^ Weller 1995, p. 123.

- ^ "The Victims". O.J. Simpson Trial News. CNN. February 3, 1985. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ Hubler, Shawn; Trounson, Rebecca (July 6, 1994). "Nicole Simpson Was Dominated by Her Husband Since She Was a Teenager". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ Alison Martino (August 29, 2014). "The Daisy in Beverly Hills". Vintage Los Angeles.

- ^ Taylor Gibbs 1996, pp. 126–128.

- ^ a b c d Rubenstein, Janine; Acosta, Nicole (May 22, 2024). "Nicole Brown Simpson's Sisters Break Their Silence Over O.J.'s Death: 'It's Very Complicated' (Exclusive)". People. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Jeff Berg, New Mexico Filmmaking (2015), p. 82-83.

- ^ Higgins, Bill (August 11, 2016). "Olympics Flashback: When O.J. Simpson Carried the Torch in L.A." The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 17, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ "Walt Disney Co.'s 'Captain EO,' the much-ballyhooed 17-minute 3-D... - UPI Archives". UPI. Retrieved December 8, 2024.

- ^ Lange, Tom; Moldea, Dan E.; Vannatter, Philip (1997). Evidence Dismissed: The Inside Story of the Police Investigation of O. J. Simpson. Pocket Books. p. 115. ISBN 0-671-00959-1.

- ^ "Child custody decision". courttv.com. Archived from the original on January 10, 2009. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- ^ "Nicole Brown Simpson's sisters want you to remember how she lived, not how she died". AP News. May 31, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Rutten, Tim; Weinstein, Henry (March 2, 1996). "Simpson Recounts Stormy Relationship With Ex-Wife". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Goldberg, Carey (October 25, 1996). "Simpson Defense Opens With Scathing Portrait of His Ex-Wife". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ a b "Judge Allow Evidence of Domestic Violence In O.J. Simpson Murder Case". Jet. Vol. 87, no. 13. February 6, 1995. p. 51. ISSN 0021-5996.

- ^ Weller, Sheila (June 12, 2014). "How O.J. and Nicole Brown's Friends Coped with Murder in Their Midst". Vanity Fair. Retrieved December 6, 2024.

- ^ a b c "OJ Simpson's slow-speed chase on June 17, 1994". Daily News. April 11, 2024. Archived from the original on April 11, 2024. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ "Did Nicole Brown Simpson's Parents Push Her To Stay With O.J. Simpson? 'American Crime Story' Tackles The Rumors". Romper. March 2, 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c Petersen, Nate (June 15, 2016). "O.J. Simpson allegedly had an affair with this 1980s music video vixen". CBS News. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Surprise letter: Nicole wrote O.J. Simpson 'beat holy hell' out of her by Linda Deutsch (January 13, 1997) from Associated Press website|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210509004135/https://apnews.com/article/d6d0ac24e31e09deeb5ca1684fefe49e 9, 2021|url-status=dead

- ^ Deutsch, Linda (January 13, 1997). "Surprise letter: Nicole wrote O.J. Simpson 'beat holy hell' out of her". Associated Press. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- ^ 'National Enquirer Investigates' Reveals O.J. Simpson's Many Mistresses by Radar staff (May 24, 2018) from Radar website

- ^ "Opinion : Never forget — Nicole Brown Simpson's murder redefined our understanding of domestic violence". Los Angeles Times. April 14, 2024. Retrieved December 6, 2024.

- ^ "Revisiting the O.J. Simpson Murder Trial: The Shocking Details, Key Players and Verdict". People.com. Retrieved December 6, 2024.

- ^ "'I'm gonna O.J. you': How the Simpson case changed perceptions — and the law — on domestic violence". Los Angeles Times. April 13, 2024. Retrieved December 6, 2024.

- ^ Swisher, Kara (July 9, 1994). "O.J. AND HERTZ: THE RISE AND FALL OF A RENT-A-STAR". The Washington Post.

- ^ results, search; Willwerth, James (October 16, 1996). American Tragedy: The Uncensored Story of the Simpson Defense (1st ed.). Random House. ISBN 9780679456827.

- ^ Weller 1995, pp. 95.

- ^ Weller 1995, pp. 121.

- ^ Darden, Chris (1996). In Contempt. Regan Books. ISBN 978-0-06-039183-6.

- ^ Lindsay (June 22, 2016). "Nicole Brown Simpson's Gretna Green House". IAMNOTASTALKER. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ Taylor Gibbs 1996, p. 136.

- ^ Weller, Sheila (June 12, 2014). "How O.J. and Nicole Brown's Friends Coped with Murder in Their Midst". Vanity Fair. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ^ Hesse, Monica (April 14, 2024). "Perspective | Nicole Brown Simpson's cries for help are still hard to hear". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ a b c Anolik, Lili (June 2014). "It All Began with O. J.". Vanity Fair. Vol. 56, no. 6. New York. pp. 108ff. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ "SIMPSON'S EX-WIFE PLEADS FOR HELP ON POLICE TAPES". Washington Post. February 25, 2024. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ Nicole Brown Simpson 911 Calls. Complete, Uncensored, Never Before Heard. ♦ OJSimpson.co Exclusive. Retrieved August 15, 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "Trial Journal". sfgate.com. March 30, 1995. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021.

- ^ Kato Kaelin's O.J. trial testimony. Retrieved April 25, 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "Who Is Keith Zlomsowitch? Nicole Brown Simpson's Boyfriend Gave Upsetting Testimony". Bustle. June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Nicole Brown Simpson's Ex Keith Zlomsowitch Smiling Over O.J. Death". TMZ. April 11, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Streeter, Leslie Gray. "Nicole Simpson's ex: 'I felt guilty, that O.J. Simpson had beaten her, because of me'". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Jack Walraven's Simpson Trial Transcripts - JUNE 8, 1995". simpson.walraven.org. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ "Jack Walraven's Simpson Trial Transcripts - MARCH 9, 1995". simpson.walraven.org. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ a b David Ellis (November 7, 1994). "A Sensational Memoir Raises Questions By—and About—One of Nicole's Pals". People. Candor or Pander?. Vol. 42, no. 19. Archived from the original on March 10, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ Faye D. Resnick with Mike Walker (October 1, 1994). Nicole Brown Simpson: The Private Diary of a Life Interrupted (2nd ed.). Dove Books. ISBN 978-1-55144-061-3.

- ^ Lindsay (March 7, 2016). "Nicole Simpson's Condo from "The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story"". IAMNOTASTALKER. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ a b Nicole Brown Simpson: The Final 24 (Full Documentary). Retrieved April 25, 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Rimer, Sara. (June 23, 1994). "Nicole Brown Simpson: Slain At the Dawn of a Better Life." The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/06/23/us/simpson-case-victim-nicole-brown-simpson-slain-dawn-better-life.html

- ^ "O.J. Simpson & Nicole Brown Simpson attend the red carpet Hollywood premiere of ‘Naked Gun 33⅓: The Final Insult.’" RetroNewsNow. (March 16, 2019). X.https://twitter.com/RetroNewsNow/status/1106992266424528900/photo/1

- ^ Mosk, Matthew & Hall, Carla (June 15, 1994). "Victim Thrived on Life in Fast Lane, His Friends Recall". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "O.J. offered ex-wife money for sex - UPI Archives". UPI.

- ^ "CNN - Simpson trial: list of upcoming witnesses - Nov. 28, 1996". edition.cnn.com. Archived from the original on June 9, 2024.

- ^ a b Kris Jenner Talks Bruce, Divorce, OJ Simpson & Ex Husband Robert Kardashian. Retrieved April 25, 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ a b Simpson & Fenjves 2006.

- ^ a b Margolick, David (July 25, 1995). "Simpson Expert Supports Conspiracy-Theory Defense". The New York Times. p. 9. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ a b Siegel, Jessica (June 13, 1995). "Gawkers Flock to Crime Scene on Bundy Avenue 1 Year Later". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Weinstein, Henry (October 8, 1995). "THE SIMPSON LEGACY / LOS ANGELES..." Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Jury didn't hear from key witnesses - UPI Archives". UPI.

- ^ "TIME OF NICOLE SIMPSON CALL DISPUTED". Deseret News. January 23, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Bugliosi 1997, p. 19.

- ^ Guerrasio, Jason (June 16, 2016). "O.J. Simpson Never-Before-Seen Crime-Scene Photos". Business Insider. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ "GOLDMAN WAS TRAPPED, CORONER SAYS". Washington Post. February 25, 2024. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved September 5, 2024.

- ^ "WITNESS HEARD VOICES, SLAMMING GATE". Deseret News. July 12, 1995. Retrieved September 5, 2024.

- ^ "Goldman family still struggles with murder". NBC News. June 14, 2004. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021.

- ^ "The People v. O.J. Simpson Criticized By Ron Goldman's Sister: "My Brother Was a Hero"". E! Online. February 4, 2016.

- ^ Shapiro 2009.

- ^ Weller1995, cited in Dear 2012.

- ^ Cerasini 1994, p. 257.

- ^ Weller 1995, p. 36.

- ^ Hardesty, Greg. "Nicole Brown Simpson's little sister grows up". Orange County Register. Santa Ana, California: Freedom Communications. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ Rimmer, Sara (June 22, 1994). "Nicole Brown Simpson: Slain At the Dawn of a Better Life". The New York Times. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ "WAS NICOLE PREPARING FOR ROMANCE?". Deseret News. February 23, 1995. Retrieved September 5, 2024.

- ^ a b Meier, Barry (September 7, 1994). "Simpson Team Taking Aim at DNA Laboratory". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ Jones, Thomas L. "O.J. Simpson". truTV. Archived from the original on December 9, 2008. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ^ "1995: OJ Simpson verdict: 'Not guilty'". On This Day: 3 October. BBC. October 3, 1995. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "The O.J. Simpson Murder Trial : Excerpts of Opening Statements by Simpson Prosecutors". Los Angeles Times. January 25, 1995. Archived from the original on April 12, 2024. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ "How O.J. Simpson's Dream Team Played the "Race Card" and Won". Vanity Fair. May 5, 2014. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "Race and Justice: Rodney King and O.J. Simpson in a House Divided | Office of Justice Programs". www.ojp.gov. Archived from the original on August 23, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "OJ Simpson Juror: Not-Guilty Verdict Was 'Payback' for Rodney King". June 15, 2016. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "Confusion for Simpson kids 'far from over'". USA Today. February 12, 1997. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ Mydans, Seth (June 18, 1994). "The Simpson Case: The Fugitive; Simpson Is Charged, Chased, Arrested". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ^ Gilbert, Geis; Bienen, Leigh B. (1988). Crimes of the century: from Leopold and Loeb to O.J. Simpson. Northeastern University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-1555533601.

- ^ Mydans, Seth (June 16, 1994). "Lawyer for O.J. Simpson Quits Case". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ^ Newton, Jim (September 9, 1994). "Power Struggle in the Simpson Camp, Sources Say – Shapiro, Cochran Increasingly Compete For Limelight In Case". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 21, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ^ "List of the evidence in the O.J. Simpson double-murder trial". USA Today. October 18, 1996. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ "Expert on Battered Women Criticized for Backing Simpson Defense". AP News. Archived from the original on May 7, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ "Court.com – Trials – O.J. Simpson: Week-by-week". February 9, 2008. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ "Jack Walraven's Simpson Trial Transcripts - Cora Fischman Deposition of March 19, 1996". simpson.walraven.org.

- ^ "the o.j. verdict: Toobin". www.pbs.org. October 4, 2005. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ "the O.J. verdict: Dershowitz". www.pbs.org. October 4, 2005. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ Chakravarti, Sonali (August 5, 2014). "The OJ Simpson Verdict, Jury Nullification and Black Lives Matter: The Power to Acquit". Public Seminar. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ Monroe, Sylvester (June 16, 2014). "Black America was cheering for Cochran, not O.J." Andscape. Archived from the original on April 1, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ Decker, Cathleen (October 8, 1995). "The Times Poll : Most in County Disagree With Simpson Verdicts". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 16, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "Most Black People Now Think O.J. Was Guilty". FiveThirtyEight. June 9, 2014. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ "O.J. Simpson jurors reflect on the history-making trial in Oxygen's The Jury Speaks". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 9, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Freed, Donald; Briggs, Raymond P. (1996). Killing Time: The First Full Investigation Into the Unsolved Murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman. MacMillan. p. 131. ISBN 9780028613406.

- ^ "Fight over money may follow court battle". Usatoday30.usatoday.com.

- ^ "Judge Fujisaki was able to keep trial in control". Usatoday30.usatoday.com. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ "Judge allows new shoe photo in Simpson trial – CNN". Archived from the original on October 11, 2012.

- ^ "Confusion for Simpson kids 'far from over'". Usatoday30.usatoday.com.

- ^ Lafferty, Elaine (February 17, 1997). "The Inside Story of How O.J. Lost". Time. pp. 32–33.

- ^ "Nicole's diary shows state of mind, judge rules". www.cnn.com. CNN. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ "Tabloid runs excerpts of Nicole's diary". www.cnn.com. CNN. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ "Rufo v. Simpson". caselaw.findlaw.com. FindLaw. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ "Race factor tilts the scales of public opinion". Usatoday30.usatoday.com.

- ^ "Court: Simpson Still Liable For $33.5M Judgment – News Story – WMAQ | Chicago". Archived from the original on October 9, 2008.

- ^ "O.J. Feels the Heat – Time". Archived from the original on April 9, 2008.

- ^ "Jury unanimous: Simpson is liable". CNN. February 4, 1997. Archived from the original on January 28, 1999. Retrieved June 16, 2008.

- ^ "Court: Simpson Still Liable For $33.5M Judgment". NBC5.com. February 21, 2008. Archived from the original on October 9, 2008. Retrieved June 16, 2008.

- ^ Shapiro, Emily (April 11, 2024). "O.J. Simpson, former football star acquitted of murder, dies at 76". ABC News. Archived from the original on April 11, 2024. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ Dolak, Kevin (April 15, 2024). "O.J. Simpson's Lawyer Reverses Opinion on Payments to Goldman Family (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- ^ Goldberg, Carey (December 26, 1996). "Simpson Wins Custody Fight for 2 Children by Slain Wife". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- ^ Okeke-Ibezim 1997, pp. 110ff.

- ^ Morello, Carol (December 21, 1996). "Judge Awards O.J. Simpson Custody of His Children". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. A1. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ "OJ Faces Further Battle over Child Custody". BBC News. November 11, 1998. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ "O J's last defender – F. Lee Bailey". The Washington Post.

- ^ "O.J. Simpson's Sister Believes He is Innocent: 'I Know He Did Not Kill Nicole and Ron'". January 12, 2017.

- ^ "O.J. Prosecutor Marcia Clark Says Upcoming TV Series 'O.J. Is Innocent' is 'Hideous'". Insideedition.com. April 5, 2016.

- ^ "'Is O.J. Innocent? The Missing Evidence': Series Concludes with Debunk of Simpson Son Theory". The Hollywood Reporter. January 17, 2017.

- ^ "Kato Kaelin reflects on O.J.'s death: 'I believe he did it,' wonders 'if he made peace with God'". Foxnews. April 11, 2024.

- ^ "A&R exec Cantor slain". Variety. August 3, 1993.

- ^ "Rose McGowan Tells All in New Memoir 'Brave': 14 Shocking Allegations". Etonline.com. January 30, 2018.

- ^ Noble, Kenneth B. (September 22, 1994). "Simpson's Attempt to Bar Evidence is Turned Down". The New York Times.

- ^ Lee Bailey, F.; Rabe, Jean (2008). When the Husband is the Suspect. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0765316134.

- ^ Bosco, Joseph (1996). A Problem of Evidence: How the Prosecution Freed O.J. Simpson. W. Morrow and Company. ISBN 978-0688144135.

- ^ Freed, Donald; Briggs, Raymond P. (1996). Killing time : The first full investigation into the unsolved murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman. Macmillan, USA. ISBN 978-0028613406.

- ^ "Goldman Friend is Slain Resisting Robbery". Deseret.com. September 12, 1995.

- ^ Brinkworth, Malcolm (October 4, 2000). "New clues in OJ Simpson murder mystery". BBC News.

- ^ "Simpson". Afrocentricnews.com.

- ^ "BBC News | Americas| New clues in OJ Simpson murder mystery". News.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "New Evidence OJ Was Framed - Police 'Almost Certainly' Planted Blood in House and Car".

- ^ "O.J. Is Innocent and I Can Prove It | William C. Dear". Billdear.com.

- ^ Alan Duke (November 21, 2012). "Documentary: Serial killer, not O.J., killed Simpson and Goldman". CNN.

- ^ "Documentary: Serial killer, not O.J., killed Simpson and Goldman". CNN. November 21, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ^ "O.J. Simpson film: Serial killer murdered Nicole Brown and Ronald Goldman 9". Toronto Sun. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ^ a b c Harris, Dan (November 20, 2012). "Serial Killer Murdered Nicole Brown Simpson, New Documentary Claims". ABC News. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ Colburn, Randall (October 17, 2019). "O.J. didn't do it, apparently, in The Murder Of Nicole Brown Simpson". Retrieved April 28, 2024.

- ^ Reyes, David (July 19, 1995). "The O.J. Simpson Murder Trial: Nicole Simpson Foundation Gives Shelter $10,000". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ Reza, H. G. (January 4, 1999). "The Brown Foundation Cuts Back on Giving". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ "Nicole Brown Simpson Charit Foundation – GuideStar Profile". www.guidestar.org. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ a b A Tribute to Nicole (VHS, 1996) Nicole Brown Simpson. Retrieved April 25, 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ The OJ Simpson Saga From The Man Who Saw It All. Retrieved April 25, 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ EXCLUSIVE: Kris Jenner Remembers Her Last Trip With Nicole Brown Simpson. Retrieved April 25, 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ a b Kris Jenner Talks Regret and the O.J. Simpson Verdict | Oprah's Next Chapter | Oprah Winfrey Network. Retrieved April 25, 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Kris Jenner & Faye Resnick Still Hurt Over Loss of Nicole Brown Simpson | KUWTK | E!. Retrieved April 25, 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Nicole Brown Simpson's sister speaks out. Retrieved April 25, 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ GReatrex, Courtney (October 25, 2019). "EXCLUSIVE: The world hasn't forgotten what OJ Simpson did to my sister". nowtolove.com.au. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ "Louis Brown, father of Nicole Brown Simpson, dies". 6abc Philadelphia. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ "OJ Simpson Says Ex-Wife Nicole Brown Simpson's Mother Has Died: 'God Bless Her Family'". NewsOne. November 9, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ Walker, Theresa (June 17, 2014). "Lingering Questions from the O.J. Simpson Chase". Orange County Register. Santa Ana, California: Freedom Communications. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Truth_Merciless. OJ Simpson - If I Did It.

- ^ Linder, Douglas O. (April 11, 2024). "Famous Trials: "IF I Did It": The Quasi-Confession of O. J. Simpson". Famous Trials by Professor Douglas O. Linder. UMKC School of Law. Archived from the original on January 12, 2024. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ a b c "ABC News Exclusive: 'If I Did It': O.J's Daughter's Idea". abcnews.com. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ Timothy Noah (November 22, 2006). "Defending If I Did It". Slate. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ^ The Goldman Family (September 13, 2007). If I Did It Confessions of the Killer. Dominick Dunne (Afterword), Pablo F. Fenjves (Foreword) (1st ed.). Beaufort Books. ISBN 978-0825305887.

- ^ "Victims' families feud over O.J.'s 'If I Did It' book". Today.com.

- ^ Snow, Shauna (January 18, 1995). "Television O.J. Simpson Film Gets Date: Fox has". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 19, 2024.

- ^ Zoller Seitz, Matt (January 25, 2016). "Ryan Murphy's The People v. O.J. Simpson Puts More Than Just Simpson on Trial". Vulture. Retrieved October 19, 2024.

- ^ Merrett, Robyn (October 17, 2019). "Mena Suvari Plays Nicole Brown Simpson in New Film About Her Murder — But with a Strange Twist". People. Retrieved October 19, 2024.

- ^ Stenzel, Wesley (April 24, 2024). "Boris Kodjoe's O.J. Simpson gets the electric chair in shocking teaser for The Juice". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved October 19, 2024.

- ^ "Nicole Brown Simpson Lifetime Doc Gets Premiere Date and Trailer: "Her Life Was Stolen From Her"". The Hollywood Reporter. May 2, 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Bugliosi, Vincent (1997) [1996]. Outrage: The Five Reasons Why O. J. Simpson Got Away with Murder. New York: Dell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-440-22382-5.

- Cerasini, Marc (1994). O.J. Simpson: American Hero, American Tragedy. New York: Windsor Publishing Corporation. ISBN 978-0-7860-0118-7.

- Dear, William C. (2012). O. J. Is Innocent and I Can Prove It: The Shocking Truth About the Murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-63220-072-3.

- Hunt, Darnell M. (1999). O. J. Simpson Facts and Fictions: News Rituals in the Construction of Reality. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511489204. ISBN 978-0-521-62468-8.

- Lange, Tom; Vannatter, Philip; Moldea, Dan E. (1997). Evidence Dismissed: The Inside Story of the Police Investigation of O. J. Simpson. New York: Pocket Books.

- Okeke-Ibezim, Felicia (1997). O.J. Simpson: The Trial of the Century. New York: Ekwike Publications. ISBN 978-0-9661598-0-6.

- Schmalleger, Frank (1996). Trial of the Century: People of the State of California vs. Orenthal James Simpson. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-235953-5.

- Shapiro, Robert L. (2009) [1996]. The Search for Justice: A Defense Attorney's Brief on the O.J. Simpson Case. Boston: Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-57007-7.

- Simpson, O. J.; Fenjves, Pablo (2006). If I Did It (cancelled ed.). ReganBooks.

- Taylor Gibbs, Jewelle (1996). Race and Justice: Rodney King and O. J. Simpson in a House Divided. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 978-0-7879-0264-3.

- Weller, Sheila (1995). Raging Heart: The Intimate Story of the Tragic Marriage of O.J. and Nicole Brown Simpson. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 978-0-671-52145-5.

External links

[edit]- 1959 births

- 1994 deaths

- 1994 murders in the United States

- 20th-century German people

- 20th-century German women

- Catholics from California

- Deaths by stabbing in California

- Female murder victims

- Emigrants from West Germany to the United States

- German murder victims

- German people of American descent

- German people murdered abroad

- German Roman Catholics

- Incidents of violence against women

- O. J. Simpson

- O. J. Simpson murder case

- People from Brentwood, Los Angeles

- People from Frankfurt

- People murdered in Los Angeles

- Dana Hills High School alumni

- 20th-century American people

- 20th-century American women

- Unsolved murders in the United States