RSPCA

Logo as of April 2024 | |

| Formation | 16 June 1824 |

|---|---|

| Founders | |

| Type | Nonprofit |

| Focus | Animals |

| Headquarters | Horsham, West Sussex, England |

Area served | England and Wales |

Key people | Chris Sherwood (CEO, August 2018 – present) |

| Revenue | £151.7m (2021)[1] |

| Employees | 1,305 (2021) |

| Website | rspca |

The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) is a charity operating in England and Wales which promotes animal welfare. The RSPCA is funded primarily by voluntary donations. Founded in 1824, it is the oldest and largest animal welfare organisation in the world,[2] and is one of the largest charities in the UK.[3] The organisation also does international outreach work across Europe, Africa and Asia.[4]

The charity's work has inspired the creation of similar groups in other jurisdictions, starting with the Ulster Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (founded in 1836), and including the Scottish Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (1839), the Dublin Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (1840), the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (1866), the Royal New Zealand Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (1882), the Singapore Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (1959) and various groups which eventually came together as the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Australia (1981), the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Hong Kong) (1997) – formerly known as the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Hong Kong) (1903–1997).

History

[edit]This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (December 2020) |

Changing political climate

[edit]The emergence of the RSPCA has its roots in the intellectual climate of the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Britain where opposing views were exchanged in print concerning the use of animals. The harsh use and maltreatment of animals in hauling carriages, scientific experiments (including vivisection), and cultural amusements of fox-hunting, bull-baiting and cock fighting were among some of the matters that were debated by social reformers, clergy, and parliamentarians.[5] At the beginning of the 19th century there was an unsuccessful attempt by Sir William Pulteney on 18 April 1800 to pass legislation through the British parliament to ban the practice of bull-baiting.[6] In 1809 Lord Erskine (1750–1823) introduced an anti-cruelty bill which was passed in the House of Lords but was defeated in a vote in the House of Commons.[7] Erskine in his parliamentary speech combined the vocabulary of animal rights and trusteeship with a theological appeal to biblical passages opposing cruelty.[8] A later attempt to pass anti-cruelty legislation was spearheaded by the Irish parliamentarian Richard Martin and in 1822 an anti-cruelty to cattle bill (sometimes called Martin's Act) became law.[9]

Formation of the SPCA and royal patronage

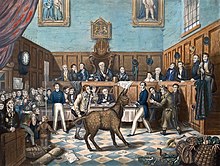

[edit]Martin's Act was supported by various social reformers who were not parliamentarians, and the efforts of the Reverend Arthur Broome (1779–1837) to create a voluntary organisation to promote kindness toward animals resulted in the founding of an informal network. Broome canvassed opinions in letters that were published or summarised in various periodicals in 1821.[10] Broome organised a meeting and extended invitations to various reformers that included parliamentarians, clergy and lawyers. The meeting was held on Wednesday 16 June 1824 in Old Slaughter's Coffee House, London.[11] The meeting was chaired by Thomas Fowell Buxton MP (1786–1845) and the resolution to establish the society was voted on. Among the others who were present as founding members were Sir James Mackintosh MP, Richard Martin, William Wilberforce, Basil Montagu, John Ashley Warre, the Rev. George Bonner, the Rev. George Avery Hatch, Sir James Graham, John Gilbert Meymott, William Mudford, and Lewis Gompertz.[12] The organisation was founded as the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Broome was appointed as the society's first honorary secretary.[13] The foundation is marked by a plaque on the modern day building at 77–78 St Martin's Lane.[14]

The society was the first animal welfare charity to be founded in the world.[15] In 1824 it brought 63 offenders before the courts.[16] Princess Victoria became the society's patron in 1835,[11] and, as Queen, granted its royal status in 1840 to become the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, as it is today.[17]

RSPCA Inspectors

[edit]The origins of the role of the RSPCA inspector stem from Broome's efforts in 1822 to personally bring to court some individuals against whom charges of cruelty were heard.[18] Broome employed and personally paid the salary for an inspector to monitor the abuse of animals at the Smithfield Market.[19] The inspector hired by Broome, Charles Wheeler, served in the capacity of an inspector from 1824 to 1826 but his services were terminated when the society's revenue was exceeded by its debts. The accrued debts led to a suspension of operations when Broome as the society's guarantor for debts was imprisoned.[20] When operations resumed there was some divided opinions in the committees that steered the society about employing inspectors, which resulted in a resolution in 1832 to discontinue employing an inspector. The permanent appointment of a salaried inspector was settled in 1838, and the inspector is the image best known of the organisation today.[21]

Broome's experience of bankruptcy and prison created difficulties for him afterwards and he stood aside as the society's first secretary in 1828 and was succeeded by the co-founding member Lewis Gompertz.[22] Unlike the other founder members who were Christians, Gompertz was a Jew and despite his abilities in campaigning against cruelty, fund-raising and administrative skills, tensions emerged between him and other committee members, due to Gompertz's approach, considered very radical at the time, in opposition to hunting and other forms of using animals he regarded as abusive.[23][24] The tensions led to the convening of a meeting in early 1832 which led to Gompertz resigning.[25] His resignation coincided with a resolution adopted in 1832 that "the proceedings of the Society were entirely based on the Christian faith and Christian principles."[26]

Impacting public opinions

[edit]Alongside the society's early efforts to prosecute offenders who maltreated animals, there were efforts made to promote kindly attitudes toward animals through the publication of books and tracts as well as the fostering of annual sermons preached against cruelty on behalf of the society. The first annual anti-cruelty sermon that was preached on behalf of the society was delivered by Rev Dr Rudge in March 1827 at the Whitechapel Church.[27] In 1865 the RSPCA looked for a way to consolidate and further influence public opinion on animal welfare by encouraging an annual "Animal Sunday" church service where clergy would preach sermons on anti-cruelty themes and the very first sermon was delivered in London on 9 July 1865 by the Rev. Arthur Penrhyn Stanley (1815–1881), the Dean of Westminster.[28] The "Animal Sunday" service became an annual event in different church gatherings in England, which was later adopted by churches in Australia and New Zealand in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and it was the forerunner of the "pet blessing" services that emerged in the 1970s.[29] In the twentieth century the RSPCA widened the horizons in the public domain by promoting an annual "animal welfare week".[30]

The RSPCA also had annual accounts published in newspapers, like The Londoner, where the secretary would discuss improvements, report cases, and remind the public to watch over their animals' health.[31]

During the second half of 1837 the society sponsored an essay-writing competition with a benefactor offering a prize of one hundred pounds for the winning entry. The terms of the competition stipulated:

"The Essay required is one which shall morally illustrate, and religiously enforce, the obligation of man towards the inferior and dependent creatures – their protection and security from abuse, more especially as regards those engaged in service, and for the use and benefit of mankind-on the sin of cruelty – the infliction of wanton or unnecessary pain, taking the subject under its various denominations – exposing the specious defence of vivisection on the ground of its being for the interests of science – the supplying the infinite demands on the poor animal in aid of human speculations by exacting extreme labour, and thereby causing excessive suffering – humanity to the brute as harmonious with the spirit and doctrines of Christianity, and the duty of man as a rational and accountable creature."[32]

There were 34 essays submitted and in December 1838 the prize was awarded to the Congregational minister Rev John Styles.[33] Styles published his book-length work, The Animal Creation; its claims on our humanity stated and enforced, and all proceeds of sale were donated to the society.[34] Other contestants, such as David Mushet and William Youatt, the society's veterinarian, also published their essays.[35] One entrant whose work was submitted a few days after the competition deadline, and which was excluded from the competition was written by the Unitarian minister William Hamilton Drummond and he published his text in 1838, The Rights of Animals: And Man's Obligation to Treat Them with Humanity.[36] This competition set a precedent for subsequent RSPCA prize-winning competitions.

Women in the RSPCA

[edit]

The role of women in the society began shortly after the organisation was founded. At the society's first annual meeting in 1825, which was held at the Crown and Anchor Tavern on 29 June 1825, the public notice that announced the gathering specifically included appropriate accommodation for the presence of women members.[37] Several women of social standing were listed as patronesses of the society, such as the Duchess of Buccleuch, Dowager Marchioness of Salisbury, Dowager Countess Harcourt, Lady Emily Pusey, Lady Eyre and Lady Mackintosh.[38] In 1837 the novelist Catherine Grace Godwin (1798–1845) described in her novel Louisa Seymour an incident where two leading female characters were aghast at the behaviour of a driver abusing a horse pulling a carriage that they subsequently discussed the problem of cruelty with other characters one of whom, called Sir Arthur Beauchamp, disclosed that he was a member of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.[39] In 1839 another female supporter of the society, Sarah Burdett, a relative of the philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts and a poet, published her theological understanding of the rights of animals.[40] However it was not until 12 July 1870 that the RSPCA Ladies' Committee was established.[41] Through the Ladies Committee various activities were sponsored including essay-prize competitions among children, and the formation of the Band of Mercy as a movement to encourage children to act kindly toward animals.[42]

Women were debarred from membership of the RSPCA's executive committee until 1906.[43]

International relations

[edit]In the 19th century the RSPCA fostered international relations on the problem of cruelty through the sponsoring of conferences and in providing basic advice on the establishment of similar welfare bodies in North America and in the colonies of the British Empire.[44] The RSPCA celebrated its jubilee in June 1874 by holding an International Congress on Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and Queen Victoria delivered a letter of congratulations to the RSPCA on its anniversary.[45] Although the society was founded by people who were mostly Christian social reformers, and in 1832 presented itself as a Christian charity concerned with welfare as well as moral reform, the RSPCA gradually developed into a non-religious, non-sectarian animal welfare charity.[46]

Lobbying for legal change

[edit]The RSPCA lobbied Parliament throughout the 19th century, resulting in a number of new laws. The Cruelty to Animals Act 1835 amended Martin's Act and outlawed baiting. There was a public groundswell of opinions that were divided into opposing factions concerning vivisection, where Charles Darwin (1809–1882) campaigned on behalf of scientists to conduct experiments on animals while others, such as Frances Power Cobbe (1822–1904) formed an anti-vivisection lobby.[47] The stance adopted by the RSPCA was one of qualified support for legislation.[48] This qualified support for experiments on animals was at odds with the stance taken by Society's founder Broome who had in 1825 sought medical opinions about vivisection and he published their anti-vivisection sentiments.[49] It was also a departure from the 1837 essay-competition (discussed above) where the essayists were obliged to expose "the specious defence of vivisection on the ground of its being for the interests of science." In 1876 the Cruelty to Animals Act was passed to control animal experimentation. In 1911 Parliament passed Sir George Greenwood's Animal Protection Act. Since that time the RSPCA has continued to play an active role, both in the creation of animal welfare legislation and in its enforcement. An important recent new law has been the Animal Welfare Act 2006 (c. 45).[50][51]

First World War – present

[edit]During the First World War the RSPCA provided support for the Army Veterinary Corps in treating animals such as donkeys, horses, dogs and birds that were co-opted into military service as beasts of burden, messengers and so forth.[52] However, the RSPCA estimates that 484,143 horses, mules, camels and bullocks were killed in British service during the war.[53]

The RSPCA's centenary in 1924 and its 150th anniversary in 1974 were accompanied by books telling the society's story.[54] During World War II it was reported that the RSPCA had rescued 256,000 animals during bombing raids. Bernard Montgomery sent a letter of appreciation to the RSPCA, commenting that the Society had alleviated the suffering of animals during the war.[55]

Since the end of the Second World War the development of intense agricultural farming practices has raised many questions for public debate concerning animal welfare legislation and the role of the RSPCA. This development has included debates both inside the RSPCA (e.g. the RSPCA Reform Group) as well as among ethicists, social activists and supporters of claims for animal rights outside of it concerning the society's role in ethical and legal issues involving the use of animals.[56]

Publications

[edit]The RSPCA's official publication, The Animal World: A Monthly Advocate of Humanity was released in October 1869. It was inspired by the MSPCA's publication Our Dumb Animals which had been created a year before.[57] The Animal World magazine defined its objective as "to protect animals from torture and ameliorate their condition, and to awaken in the minds of men a proper sense of the claims of creatures placed under their dominion".[58] It was edited by John Colam the then secretary of the RSPCA from 1869–1905.[59] In 1883, the RSPCA Ladies' Committee took over the Band of Mercy's magazine The Bang of Mercy Advocate and renamed it simply, Band of Mercy.[58] Colam was also its editor until 1905.[59] Both magazines were formed to educate people about treating animals more kindly.[60] The Animal World magazine was published up until the 1990s. Copies are stored at the RSPCA Archive in Horsham, West Sussex and digitized by the NC State University Libraries.[61][62]

The RSPCA currently publishes an annual review and the Animal Life magazine twice a year for members.[63]

Animal welfare establishments

[edit]RSPCA centres, hospitals and branches operate throughout England and Wales. In 2012 RSPCA centres and branches assisted and rehomed 55,459 animals.[64]

Hospitals

[edit]In 2013 the society owned four animal hospitals, Birmingham, Greater Manchester, Putney (south London) and the Harmsworth Memorial Hospital in Finsbury Park (north London),[65] and a number of clinics which provide treatments to those who could not otherwise afford it, neuter animals, and accept animals from the RSPCA inspectorate. As of September 2020, the Putney Animal Hospital has been permanently closed.[66]

Centres

[edit]RSPCA animal centres deal with a wide range of injured and rescued animals, working alongside its inspectorate, volunteers, and others to ensure that each animal is found a new home. There are currently 17 RSPCA animal centres across the UK and a further 42 centres ran independently by Branches.[67]

In 2013 the society had four wildlife centres at East Winch (Norfolk), West Hatch (Somerset), Stapeley Grange (Cheshire) and Mallydams Wood (East Sussex), which provide treatment to sick, injured and orphaned wild animals to maximise their chances of a successful return to the wild.[65]

| Centre name | Location | Managed by |

| Bath Cats & Dogs Home | Bath & District Branch | |

| Longview Kennels | Blackpool & North Lancs Branch | |

| Bolton Branch Advice Centre | Bolton Branch | |

| Bridlington Cattery | Bridlington, Driffield & District Branch | |

| Bristol Animal Rescue Centre | Bristol & District Branch | |

| Burton upon Trent & District Branch Animal Centre | Burton upon Trent & District Branch | |

| Bury Oldham and District Branch Animal Centre | Bury Oldham & District Branch | |

| Canterbury & District Animal Centre | Hersden, Canterbury | Canterbury & District Branch |

| Enfield Cattery | Enfield | Central, West & North East London Branch |

| RSPCA Emergency Fostering Unit | Central, West & North East London Branch | |

| Chesterfield Animal Centre | Chesterfield & North Derbyshire Branch | |

| The William & Patricia Venton Animal Centre | St Columb, Cornwall | Cornwall Branch |

| Coventry Animal Centre | Coventry, Nuneaton & District Branch | |

| Danaher Animal Home | Braintree | Danaher Animal Trust |

| Derby Shelter | Derby & District Branch | |

| South Yorkshire Animal Centre | Bawtry | Doncaster, Rotherham & District Branch |

| Halifax, Huddersfield, Bradford & District Animal Centre | Halifax, Huddersfield, Bradford & District Branch | |

| Hull & East Riding Animal Centre | Hull & East Riding Branch | |

| Godshill Animal Centre | Godshill, Isle of Wight | Isle of Wight Branch |

| Woodchurch Animal Centre | Woodchurch, Birchington | Kent-Isle of Thanet Branch |

| Ashford Garden Cattery | Ashford, Kent | Kent, Ashford, Tenterden & District Branch |

| Altham Animal Centre | Lancashire East Branch | |

| Leeds, Wakefield & District Branch Animal Centre | Leeds, Wakefield & District Branch | |

| Woodside Animal Centre | Leicester | Leicestershire Branch |

| Lincoln Animal Welfare Centre | Lincolnshire Mid & Lincoln Branch | |

| Scunthorpe Animal Welfare Centre | Lincolnshire North & Humber Branch | |

| Halewood Animal Centre | Halewood, Liverpool | Liverpool Branch |

| Llys Nini Animal Centre | Penllergaer, Swansea | Llys Nini serving Cardiff to Swansea Branch |

| Medway RSPCA Rehoming Centre | Chatham | Medway West Branch |

| Norfolk West Branch Animal Centre | Tilney All Saints, King's Lynn | Norfolk West Branch |

| North Somerset Animal Welfare Centre | Weston-Super-Mare | North Somerset Branch |

| Brent Knoll Animal Centre | Brent Knoll, Highbridge | North Somerset Branch |

| Hope Cattery | Brixworth, Northampton | Northamptonshire Branch |

| Preston Animal Centre | Preston & District Branch | |

| RSPCA Radcliffe Shelter Trust | Radcliffe on Trent | Radcliffe Animal Trust |

| Rochdale Animal Centre | Rochdale & District Branch | |

| Bryn-Y-Maen Animal Centre | Colwyn Bay, North Wales | RSPCA |

| Gonsal Farm Animal Centre | Shrewsbury | RSPCA |

| Birmingham Animal Centre | Frankley, Birmingham | RSPCA |

| Newport Animal Centre | Hartridge Farm Road, Newport | RSPCA |

| Great Ayton Animal Centre | Great Ayton, Middlesbrough | RSPCA |

| Blackberry Farm Animal Centre | Quainton, Aylesbury | RSPCA |

| Felledge Animal Centre | Chester Moor, Chester-le-Street | RSPCA |

| Block Fen Animal Centre | Wimblington, March | RSPCA |

| West Hatch Animal Centre | Taunton | RSPCA |

| Southridge Animal Centre | Potters Bar | RSPCA |

| Southall Cattery* | Southall | RSPCA |

| Millbrook Animal Centre | Chobham, Woking | RSPCA |

| RSPCA Friern Barnet Adoption Centre | Friern Barnet, London | RSPCA |

| Ashley Heath Animal Centre | Ashley Heath, Ringwood | RSPCA |

| Lockwood Centre For Horses & Donkeys* | Wormley, Godalming | RSPCA |

| South Godstone Animal Centre* | South Godstone | RSPCA |

| Leybourne Animal Centre | Leybourne, West Malling | RSPCA |

| Greater Manchester Animal Hospital | RSPCA Hospital | |

| Birmingham Animal Hospital | RSPCA Hospital | |

| Southall Clinic | Southall | RSPCA Hospital |

| Edmonton Clinic | London | RSPCA Hospital |

| Harmsworth Memorial Animal Hospital | Holloway, Lindon | RSPCA Hospital |

| Putney Animal Hospital* | London | RSPCA Hospital |

| Merthyr Tydfil Clinic | Merthyr Tydfil | RSPCA Hospital |

| Sheffield Animal Centre | Sheffield Branch | |

| Stubbington Ark | Stubbington, Fareham | Solent Branch |

| Cotswolds Dogs and Cats Home | Cambridge | South Cotswolds Branch |

| Little Valley Animal Shelter | Bakers Hill, Exeter | South, East & West Devon Branch |

| Southport, Ormskirk & District Branch Animal Centre | Southport, Ormskirk & District Branch | |

| Whaley Bridge District Auxiliary Animal Advice Centre | Stockport, East Cheshire & West Derbyshire Branch | |

| Martlesham Animal Centre | Woodbridge | Suffolk East & Ipswich Branch |

| Brighton Animal Centre inc RSPCA Reptile Rescue | Patcham, Brighton | Sussex Brighton & East Grinstead Branch |

| Mount Noddy Animal Centre | Eartham, Chichester | Sussex Chichester & District Branch |

| Bluebell Ridge Cat Rehoming Centre | Hastings | Sussex East & Hastings Branch |

| Headcorn Cattery | Headcorn, Ashford | Tunbridge Wells & Maidstone Branch |

| Warrington, Halton & St Helens Animal Centre | Warrington | Warrington, Halton & St Helens Branch |

| Taylor's Animal Rehoming Centre | Kingston Maurward College, Dorchester | West Dorset Branch |

| Wigan, Leigh & District Branch PAWS Centre | Wigan | Wigan, Leigh & District Branch |

| Wirral & Chester Animal Centre | Wallasey, Wirral | Wirral & Chester Branch |

| The Holdings Animal Centre | Kempsey, Worcester | Worcester & Mid-Worcestershire Branch |

| York Animal Home | York | York, Harrogate & District Branch |

*closed as of September 2020[66]

Organisation and structure

[edit]National organisation

[edit]At the national level, the charity comprises all central functions, and a number of animal hospitals and centres. This national charity also employs local inspectors and AROs to respond to urgent calls. In additional to this there is a National Control Centre which takes calls from the public and helps ensure that RSPCA officers attend incidents where animals need help, the National Control Centre is however, a third party contract and are not RSPCA employees.[68]

In previous years the National Headquarters located at Southwater in West Sussex houses several general departments, each with a departmental head, consistent with the needs of any major organisation. The current chief executive officer is Chris Sherwood.[69] Since the pandemic the RSPCA no longer has a National Headquarters, with most employees now working from home and small satellite offices being set up in locations such as Horsham and London.

Regions

[edit]There are three regions ("North", "South", and "East, Midlands and Wales"), each headed by a regional superintendent who has responsibility for the chief inspectors, inspectors and AROs. The regional managers are expected to have a broad understanding of operations throughout their regions.

Branches

[edit]

RSPCA branches operate locally across England and Wales. Branches are separately registered charities operating at a local level and are run by volunteers. Some RSPCA branches are self-funding and raise money locally to support the animal welfare work they do. They find homes for about three-quarters of all animals taken in by the RSPCA. RSPCA branches also offer advice, microchipping, neutering and subsidised animal treatments. In 2013 there were also about 1000 RSPCA shops.

Groups

[edit]Each region of the RSPCA contains groups of inspectorate staff. A group is headed by a chief inspector, who might typically be responsible 6-12 officers (Inspector and AROs), working with several local branches. There is also a small number of market inspectors across the country.[70]

Inspectorate rank insignia

[edit]Mission statement and charitable status

[edit]The RSPCA is a registered charity (no. 219099) that relies on donations from the public. The RSPCA states that its mission as a charity is, by all lawful means, to prevent cruelty, promote kindness and to alleviate the suffering of animals.

RSPCA inspectors respond to calls from the public to investigate alleged mistreatment of animals. They offer advice and assistance to improve animal welfare, and in some cases prosecute under laws such as the Animal Welfare Act 2006.

Animals rescued by the RSPCA are treated, rehabilitated and rehomed or released wherever possible.[71]

The RSPCA brings private prosecution (a right available to any civilian) against those it believes, based on independent veterinary opinion, have caused neglect to an animal under laws such as the Animal Welfare Act 2006. The society has its own legal department and veterinary surgeons amongst the resources which facilitate such private prosecutions. All prosecutions are brought via independent solicitors acting for the RSPCA, as the association has no legal enforcement powers or authority in its own right.

In May 2012 the RSPCA launched its own mobile virtual network operator service, RSPCA Mobile, in partnership with MVNO whitelabel service Shebang. RSPCA Mobile claimed to be the first charity mobile phone network in the UK.[72] The agreement included provisions such that the RSPCA would receive up to 15% of top-ups made on the network and it was expected the network would raise £50,000 in the first year of operations.[73] RSPCA Mobile ceased service in October 2014.[citation needed]

Legal standing

[edit]In 1829 when the first recognisable police force was established in England,[74][75] they adopted a similar uniform to that of RSPCA inspectors who had been wearing uniforms since the charity's beginning in 1824. This adoption has led to similarities in the RSPCA rank names and rank insignia with British police ranks, which has led some critics (such as Chris Newman, chairman of the Federation of Companion Animal Societies)[76] to suggest an attempt to "adopt" police powers in the public imagination.

An RSPCA inspector may also verbally caution a member of the public, similar to that used by the police, i.e. "You do not have to say anything. But it may harm your defence if you do not mention when questioned something which you later rely on in court. Anything you do say may be given in evidence"; this may strengthen the perception that the RSPCA has statutory powers. When Richard Girling of The Times asked about its lack of powers, a spokesman for the RSPCA said "We would prefer you didn't publish that, but of course it's up to you".[76] Chris Newman claimed that the RSPCA "impersonate police officers and commit trespass. People do believe they have powers of entry";[76] however, he did not produce any evidence of such impersonation of police officers, and the society strongly denies the allegation.

Sally Case, former head of prosecutions, insisted that RSPCA inspectors are trained specifically to make clear to pet-owners that they have no such right. They act without an owner's permission, she says, "only if an animal is suffering in a dire emergency. If the court feels evidence has been wrongly obtained, it can refuse to admit it".[76]

In 2012, a trial was halted and charges relating to nine dogs were thrown out of court after District Judge Elsey ruled that they had been wrongly seized, stating that the police and RSPCA acted unlawfully when they seized the animals without a warrant or a vet present to establish any suffering.[77]

While the Protection of Animals Act 1911 provided a power of arrest for police, the British courts determined that Parliament did not intend any other organisation, such as the RSPCA, to be empowered under the act and that the RSPCA therefore does not possess police-like powers of arrest, of entry or of search (Line v RSPCA, 1902). Like any other person or organisation that the law deems to have a duty to investigate — such as HM Revenue and Customs and local authority trading standards — the RSPCA is expected to conform to the rules in the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 so far as they relate to matters of investigation. RSPCA officers are trained to state, following giving the caution, that the person is "not under arrest and can leave at any time".

The Animal Welfare Act 2006[78] has now replaced the Protection of Animals Act 1911, and it empowers the police and an inspector appointed by a local authority. Such inspectors are not to be confused with RSPCA inspectors who are not appointed by local authorities. In cases where, for example, access to premises without the owner's consent is sought, a local authority or animal health inspector or police officer may be accompanied by an RSPCA inspector if he or she is invited to do so, as was the case in previous law.[79]

Following a series of Freedom of Information requests in 2011, to police constabularies throughout England and Wales[80] it was revealed that the RSPCA has developed local information sharing protocols with a number of constabularies, allowing designated RSPCA workers access to confidential information held on the Police National Computer (PNC). Although RSPCA workers do not have direct access to the PNC, information is shared with them by the various police constabularies which would reveal any convictions, cautions, warnings, reprimands and impending prosecutions. Information regarding motor vehicles can also be accessed. The Association of Chief Police Officers released a statement clarifying that the RSPCA had no direct access to the PNC, and that in common with other prosecuting bodies, it may make a request for disclosure of records. This indirect access does not include any information that the RSPCA does not need in order to prosecute a case at court.[81]

Controversy and criticism

[edit]1925 film

[edit]

In 1925, Ada Cole and Jules Ruhl produced a controversial film for the RSPCA depicting the inhumane slaughter of export horses in Belgium that featured graphic footage taken at the village of Terhagon in 1914.[82][83] Cole and Ruhl produced the film to aid their goal in obtaining the prohibition of live export of horses for slaughter.[84][85]

In October 1925, the Departmental Committee of the Ministry of Agriculture published a report which concluded that the footage showing horses being stabbed to death was staged and filmed on a street.[86][87] The Committee alleged that butchers were paid to kill the horses for the Society's film and the method of killing them with a knife without previous stunning was no longer used in Belgium during this period.[88][87] Captain Robert Gee alleged that the film contained fake footage for the RSPCA's financial profit.[89] It became known as a "faked film" and damaged the public reception of the RSPCA.

All charges were denied by the RSPCA who noted that the film had only been shown on several private occasions, one of which was for the Departmental Committee's viewing.[85] Edward G. Fairholme, chief secretary of the RSPCA defended the film, stating that "it is absolutely false to say that the films were in any way faked, or that they were taken in the street. Enlarged photographs prove that the films were taken in the slaughter yards of the butcheries".[84] Jules Ruhl was summoned by the Departmental Committee and affirmed on his honour that the film was genuine.[90] He stated that he had recently spoken to the police and slaughtermen in Terhagon who confirmed that stabbing was the method of slaughtering used in that part of the country in 1914.[82][88] In regard to the Committee's conclusion, Cole suggested that this "can only mean that in 1914 Monsieur Ruhl and I concocted a cruel and disgraceful plot and that in 1925 we lied before the committee".[90]

Cole denied the faked film allegations, arguing that the butcher and slaughterers who took part in the film were not paid by the Society and only received a small sum in the nature of tips.[83] According to Cole; the slaughtering of horses was going on every Monday in villages near Antwerp and the film was genuine in depicting the method of slaughter that was used in the area at the time. The film was shot with arrangements with the Belgian police and was filmed in Terhagon, near Antwerp.[83]

A butcher, Frans Cools of Willebroek, signed an affidavit declaring that he was paid for his services.[83] This was denied by Cole who stated that the film was not taken in Willebroek.[83] The film was first shown by the RSPCA to the public on November 23, 1925 at Central Hall, Westminster.[88][91] Women in the audience were in tears during the scenes of slaughter and were carried out of the hall.[88] Captain Robert Gee who was present at the meeting repeated his allegations that the film was fake and had been made for financial profit but was not allowed to publicly speak to the crowd.[88][92] Lord Banbury of the RSPCA and a London magistrate Cecil Chapman defended the film and denied all allegations.[82][88] In January 1926, the RSPCA hired Messrs, Lewis and Lewis solicitors to issue a writ against Captain Gee, claiming damages for slander.[92][93]

RSPCA Assured

[edit]The RSPCA operates a not-for-profit farm animal welfare assurance scheme. All farms on the RSPCA Assured scheme must comply with the RSPCA's "stringent higher welfare standards".[94] RSPCA Assured assesses farms, hauliers and abattoirs and if they meet every standard, the RSPCA Assured label can be used on their food product.[95] The RSPCA Assured scheme has received criticism from media coverage of animal cruelty that has taken place on RSPCA Assured farms.[96][97][98]

Fundraising in Scotland

[edit]In 2009 the RSPCA was criticised by the Scottish SPCA for fundraising in Scotland and thereby "stealing food from the mouths of animals north of the border by taking donations intended for Scotland."[99] The RSPCA insists that it does not deliberately advertise in Scotland but that many satellite channels only enabled the organisation to purchase UK-wide advertising. In a statement, the RSPCA said it went "to great lengths" to ensure wherever possible that adverts were not distributed outside England and Wales, and "Every piece of printed literature, television advertising and internet banner advertising always features the wording 'The RSPCA is a charity registered in England and Wales'". "All Scottish donors, who contact us via RSPCA fundraising campaigns, are directed to the Scottish SPCA so that they can donate to them if they so wish."[99] The Scottish SPCA changed its logo in 2005 to make a clearer distinction between itself and the RSPCA in an attempt to prevent legacies being left to its English equivalent by mistake when the Scottish charity was intended.[100]

Political lobbying

[edit]The RSPCA is an opponent of badger culling; in 2006 there was controversy about a "political" campaign against culling, with the Charity Commission being asked to consider claims that the charity had breached guidelines by being too overtly political. The charity responded saying that it took "careful account of charity law and the guidance issued by the Charity Commission".[101] Years later, an RSPCA advertisement published in the Metro newspaper said: "The UK Government wants to shoot England's badgers. We want to vaccinate them – and save their lives." However, more than 100 people complained to the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), saying the use of the term "exterminate" was misleading. The advertising standards watchdog judged that the advert was likely to mislead the general public who had not taken an active interest in the badger cull saying, "The ad must not appear again in its current form. We told the RSPCA not to use language that implied the whole badger population in the cull areas would be culled in future advertising."[102] An RSPCA spokesman said it "welcomed" the judgement of the ASA to dismiss three of the areas of complaint about their advert but "respectfully disagreed" with the complaint which had been upheld.[103]

In September 2013 the RSPCA deputy chairman Paul Draycott said that 'too political' campaigns threatened the charity's future and could deter donors.[104] Draycott said that the RSPCA could go insolvent "We have spent months discussing where we want to be in 10 years' time, but unless we develop a strategy for now we won't be here then". In response the chairman Mike Tomlinson said "The trustee body continues to place its full support behind the RSPCA's chief executive, management and all our people who do such outstanding work". The accusations of politicisation remain unsubstantiated.

Paul Draycott also warned that the RSPCA fears an exodus of "disillusioned staff" with "poor or even non-existent management training and career paths" for employees. In response the RSPCA's chief executive, Gavin Grant denied suggestions in the memo that there was "no strategy" in some areas, stating that there was no difficulty in attracting trustees or serious internal concerns about management.[105]

In June 2014 RSPCA campaigner Peta Watson-Smith compared the conditions livestock are brought up in across the country to that of the Jews during the Holocaust. The comments were condemned by countryside campaigners and Jewish groups.[106] In 2015 Watson-Smith was elected to the RSPCA ruling council. At the same election the RSPCA members also voted to give a seat on the ruling council to Dan Lyons.[citation needed]

In 2016 the new head of the RSPCA, Jeremy Cooper, made a dramatic, public apology for the charity's past mistakes and vowed to be less political and bring fewer prosecutions in the future.[107] The new chief executive admitted that RSPCA had become "too adversarial" and will now be "a lot less political".[108] Cooper said that the charity had alienated farmers in its aggressive campaign against the government's badger cull and disclosed that it would be "very unlikely" to ever bring another prosecution against a hunt. Cooper later resigned after just on year in charge.[109]

In April 2019 the RSPCA has faced a new fraud investigation held at south-east London branch over the alleged mishandling of funds by two men, who were arrested on suspicion of fraud. The suspected fraud was exposed during a financial audit of the south-east London branch.[110]

Euthanasia controversies

[edit]The RSPCA also state that whilst a few of their own branches operate "no kill" policies themselves,[111] its policy on euthanasia is:

The RSPCA is working for a world in which no rehomable animal is put to sleep. Currently the RSPCA accepts, with great reluctance that in certain circumstances euthanasia may be necessary, when the animal is not rehomable, because it is sick or injured, for behavioural reasons or occasionally because there are no appropriate homes available and the animal would therefore endure long-term suffering through deprivation of basic needs.[112]

There have been incidents where the RSPCA has apologised for decisions to euthanise animals.[113] In 2008, the RSPCA was sued by Hindu monks over the killing of a sacred cow at the Bhaktivedanta Manor Hindu temple in Hertfordshire and 200 people protested at the RSPCA headquarters. On 13 December 2008, the RSPCA admitted culpability, apologised for the euthanising of the cow, and donated a pregnant cow to the temple as a symbol of reconciliation.[114][115][116]

The RSPCA admitted that in 2014 it had euthanised 205 healthy horses. In one particular case 12 horses from a Lancashire farm that had been assessed by vets as being "bright, alert and responsive" and suffering no life-threatening issues were killed by the RSPCA.[117]

Prosecutions

[edit]In May 2013 former RSPCA employee Dawn Aubrey-Ward was found hanged at her home when suffering from depression after leaving the animal charity.[118] Aubrey-Ward was described by The Daily Telegraph as a whistleblower for the RSPCA's prosecution practices. The RSPCA subsequently had a meeting with the Charity Commission over its approach to prosecutions.[119]

On 7 August 2013 the BBC Radio 4 Face the Facts radio programme broadcast an episode called "The RSPCA – A law unto itself?"[120] The programme presented a number of cases of where the RSPCA has sought to hound vets and expert witnesses who had appeared in court for the defence in RSPCA prosecutions. In one case it sought to discredit the author of the RSPCA Complete Horse Care Manual (Vogel) after he appeared as an expert witness for the defence team in an RSPCA prosecution.[121] The RSPCA later released a statement saying that this is untrue and that they do not persecute vets and lawyers who appear for the defence and as defence experts. There have been thousands of lawyers taking defence cases against the RSPCA and they have only ever made a complaint about one.[122]

In November 2013 the RSPCA was accused of instigating police raids on small animal shelters with insufficient evidence that animals were being mistreated. The owners claimed that they were being persecuted because of their "no kill" policy of only putting animals down if they cannot be effectively treated.[111] The RSPCA stated that their inspectors will offer advice and guidance to help people improve conditions for their animals, and it only seeks the help of the police where it considers there is no reasonable alternative to safeguard animal welfare.[123]

Governance

[edit]The RSPCA has long been criticised for its governance with the Charity Commission describing it as below the standard expected of a large charity[clarification needed] and in August 2018 issued the society with an official warning.[124] The RSPCA made significant changes to its governance in 2019 reducing the size of its council from 28 trustees to a new board of trustees of 12 trustees with nine elected by the membership and three co-opted. The RSPCA also introduced term limits of nine years for its trustees and appointed its first independent chair, Rene Olivieri, in its 196 years of history.

Presidents

[edit]| 1861–1878 | Earl of Harrowby[125][126] |

| 1878–1893 | Lord Aberdare[126][127] |

| 1893 | Duke of York[127] |

| 1910–1916 | Duke of Teck[128][129] |

| 1919 | Prince of Wales[130][131] |

| 1951 | Robert Gower[132] |

| 1958 | Malcolm Sargent[133][134] |

| 1977–1980 | Donald Coggan[135] |

| 1980–1982 | Richard Adams[136] |

| 2020–2023 | Richard D. Ryder[137][138] |

| 2023–2024 | Chris Packham[139][140] |

See also

[edit]- Humane society

- Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB)

- Eurogroup for Animals represents organisations such as the RSPCA at the European Union level

- Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (links to other SPCA organizations worldwide)

- Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Hong Kong) — formerly Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Hong Kong) from 1903 to 1997

- Animal welfare in the United Kingdom

Bibliography

[edit]- Antony Brown, Who Cares For Animals: 150 years of the RSPCA (London: Heinemann, 1974).[141]

- Li Chien-hui, "A Union of Christianity, Humanity, and Philanthropy: The Christian Tradition and the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in Nineteenth-Century England," Society and Animals 8/3 (2000): 265–285.

- Edward G. Fairholme and Wellesley Pain, A Century of Work For Animals: The History of the RSPCA, 1824–1934 (London: John Murray, 1934).

- Lori Gruen, Ethics and Animals: An Introduction (Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011). ISBN 978-0-521-71773-1

- Hilda Kean, Animal Rights: Political and Social Change in Britain since 1800 (London: Reaktion Books, 2000). ISBN 9781861890610

- Shevawn Lynam, Humanity Dick Martin 'King of Connemara' 1754–1834 (Dublin: Lilliput Press, 1989). ISBN 0 946640 36 X

- Vaughan Monamy, Animal Experimentation: A Guide to the Issues (Cambridge UK; New York:Cambridge University Press, 2000). ISBN 0521667860

- Arthur W. Moss, Valiant Crusade: The History of the RSPCA (London: Cassell, 1961).

- Harriet Ritvo, The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Age (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1987). ISBN 0-674-03706-5

- Richard D. Ryder, Animal Revolution: Changing Attitudes Towards Speciesism Rev Ed (Oxford; New York: Berg, 2000). ISBN 978-1-85973-330-1

- Kathryn Shevelow, For The Love of Animals: The Rise of the Animal Protection Movement (New York: Henry Holt, 2008). ISBN 978-0-8050-9024-6

References

[edit]- ^ "Trustees' Report and Accounts 2021". Charity Commission.

- ^ "Dog Rescue Pages – UK dog rescue centres and welfare organizations". Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Charity Insight page on the RSPCA. Retrieved 22 November 2010". Archived from the original on 8 July 2011.

- ^ "Our international work", RSPCA. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ Rob Boddice, A History of Attitudes and Behaviours Toward Animals in Eighteenth- And Nineteenth-Century Britain: Anthropocentrism and the Emergence of Animals (Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2008).

- ^ Kathryn Shevelow, For The Love of Animals: The Rise of the Animal Protection Movement (New York: Henry Holt, 2008), pp 201-222

- ^ John Hostettler, Thomas Erskine and Trial By Jury (Hook, Hampshire: Waterside Press, 2010), 197–199.

- ^ Cruelty to Animals: The Speech of Lord Erskine in the House of Peers (London: Richard Phillips, 1809)

- ^ Evans, William David; Hammond, Anthony; Granger, Thomas Colpitts (1836). "3 Geo. IV c. 71.—An Act to prevent the cruel and improper Treatment of Cattle". A Collection of Statutes Connected with the General Administration of the Law: Arranged According to the Order of Subjects, with Notes. W. H. Bond. pp. 123–.

- ^ "To Correspondents" The Kaleidoscope, 6 March 1821 p 288. Also see The Monthly Magazine Vol. 51 April 1, 1821 p 3

- ^ a b Sheppard, F H W. "Jermyn Street Pages 271-284 Survey of London: Volumes 29 and 30, St James Westminster, Part 1. Originally published by London County Council, London, 1960". British History Online. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Lewis Gompertz, 'Fragments in Defence of Animals, and Essays on Morals, Souls and Future State' (London: Horsell, 1852), pp 174–175; Edward G. Fairholme and Wellesley Pain, A Century of Work For Animals: The History of the RSPCA, 1824–1934 (London: John Murray, 1934), p 54.

- ^ "Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals," The Times [London] Thursday 17 June 1824, p 3; "Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals" Morning Post 28 June 1824 p 2.

- ^ "City of Westminster green plaques". Archived from the original on 16 July 2012.

- ^ Arthur W. Moss, Valiant Crusade: The History of the RSPCA (London: Cassell, 1961), 20–22.

- ^ "The History of the RSPCA". Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ^ "Who we are". RSPCA.

- ^ "Inhumanity of a Drover" 'Morning Post', 27 June 1822, p 3

- ^ Fairholme and Pain, A Century of Work For Animals, p 55.

- ^ On Broome's imprisonment see The National Archives, King's Bench Prison commitments, 1826, Ref. No. PRIS 4/38, 54; and King's Bench Prison, Final Discharges 1827, Ref. No. PRIS 7/46, II. Also refer to Fairholme and Pain, A Century of Work, 60–62; Moss, Valiant Crusade, 24–25.

- ^ Moss, Valiant Crusade, 60–61

- ^ Fairholme and Pain, A Century of Work, 62–63

- ^ Gompertz, Lewis. 1997 [first edition: 1824]. Moral inquiries on the situation of man and of brutes, Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press.

- ^ See Ryder, Richard. 2000. Animal revolution, Oxford: Basil.

- ^ See Moss, Valiant Crusade, 27–28. See the Report of an Extra Meeting of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals January 13, 1832. Also see Gompertz' brief account in Fragments in Defence of Animals, 176.

- ^ Fairholme and Pain, A Century of Work, p 68

- ^ See Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 20 March 1827, p 2

- ^ Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, The Creation of Man: A Sermon preached at Whitehall Chapel 9 July 1865 (Oxford; London: Parker, 1865); Moss, Valiant Crusade, 205.

- ^ Ross Clifford and Philip Johnson, "Christian Blessings for Pets" in Taboo Or To Do? (London: Darton Longman and Todd, 2016), p 173. ISBN 978-0-232-53253-1

- ^ For example, Elsie K. Morton, "Man and the Animals: 'Welfare Week' Appeal," The New Zealand Herald, 24 October 1925, 1. Morton, "Our Friends the Animals: World Day Observance," New Zealand Herald, 3 October 1936, 8.

- ^ Morris, Alice Bradfield (24 January 1896). "The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals". The Londoner. p. 6. Retrieved 4 September 2024 – via Gale.

- ^ See David Mushet, The Wrongs of the Animal World (London: Hatchard, 1839), p xii.

- ^ See Leeds Mercury, 15 December 1838, p 7.

- ^ John Styles, The Animal Creation; its claims on our humanity stated and enforced (London: Thomas Ward, 1839). A modern edition of Styles, which was introduced by Gary Comstock, was published by Edwin Mellen Press: Lewiston, New York, 1997. ISBN 0-7734-8710-7

- ^ Mushet, The Wrongs of the Animal World; William Youatt, The Obligation and Extent of Humanity to Brutes (London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green and Longman, 1839).

- ^ William Hamilton Drummond (1838). The Rights of Animals: And Man's Obligation to Treat Them with Humanity. Harvard University. J. Mardon.

- ^ See the public notice in Morning Post 24 June 1825 p 1.

- ^ See a longer list of patronesses in Gompertz, Fragments in Defence of Animals, p 174.

- ^ Catherine Grace Godwin, Louisa Seymour; or, Hasty Impressions (London: John W. Parker, 1837) p 91.

- ^ Sarah Burdett, The Rights of Animals; or, The Responsibility and Obligation of Man in the treatment he is bound to observe towards the animal creation (London: John Mortimer, 1839).

- ^ Moss, Valiant Crusade, 199.

- ^ Moss, Valiant Crusade, 197–198.

- ^ Donald, Diana (2020). "The early history of the RSPCA: its culture and its conflicts". Oxford Academic. Archived from the original on 8 September 2024.

- ^ Petrow, Stefan (2012). "Civilizing Mission: Animal Protection in Hobart 1878–1914". Britain and the World. 5: 69–95. doi:10.3366/brw.2012.0035.

- ^ See "Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Letter from the Queen," Western Times 24 June 1874, p 4;"Prevention of Cruelty to Animals" Manchester Courier 24 June 1874, p 5

- ^ On the role of Christians in forming voluntary organisations for moral reform and social change in nineteenth century Britain see M. J. D. Roberts, Making English Morals: Voluntary Associations and Moral Reform in England, 1787–1886 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004). ISBN 0 521 83389 2

- ^ See Rod Preece, "Darwinism, Christianity, and the Great Vivisection Debate," Journal of the History of Ideas 64/3 (2003): 399–419. Boddice, A History of Attitudes and Behaviours Toward Animals in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Britain, pp 304-339.

- ^ Moss, Valiant Crusade, 154–172.

- ^ "Cruelty to Animals" Morning Post, 10 November 1825, p 1

- ^ "DEFRA page on Animal Welfare Act 2006. Retrieved 22 November 2010". Archived from the original on 15 March 2010.

- ^ "Animal Welfare Act". RSPCA.

- ^ See Fairholme and Pain, A Century of Work, 204–224. Also see John M. Kistler, Animals in the Military: From Hannibal's Elephants to the Dolphins of the U.S. Navy (Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2011). ISBN 978-1-59884-346-0.

- ^ "The animal victims of the first world war are a stain on our conscience". The Guardian. 7 November 2018.

- ^ Fairholme and Pain, A Century of Work. Brown, Who Cares For Animals? (London: Heinemann, 1974)

- ^ "The History of the RSPCA". Michigan State University. 2024. Archived from the original on 22 September 2024.

- ^ Richard D. Ryder, Animal Revolution: Changing Attitudes Towards Speciesism Rev Ed (Oxford; New York: Berg, 2000), 163–193. Hilda Kean, Animal Rights: Political and Social Change in Britain since 1800 (London: Reaktion Books, 1998) 201–214.

- ^ Davis, Janet M. (2016). The Gospel of Kindness Animal Welfare and the Making of Modern America. Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0199733156

- ^ a b Flegel, Monica (2012). "'How Does Your Collar Suit Me?': The Human Animal in the RSPCA'S 'Animal World' and 'Band of Mercy'". Victorian Literature and Culture. 40 (1): 247–262. JSTOR 41413831.

- ^ a b Burkhardt, Frederick. (2001). The Correspondence of Charles Darwin 12, 1864. Cambridge University Press. p. 544. ISBN 0-521-59034-5

- ^ Feuerstein, Anna. (2019). The Political Lives of Victorian Animals Liberal Creatures in Literature and Culture. Cambridge University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-1108492966

- ^ Medlock, Chelsea (2021). "RSPCA Archives at Horsham, UK". Dissertation Reviews. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals". NC State University Libraries. 2024. Archived from the original on 2 September 2024.

- ^ "Publications and news". RSPCA. 2024. Archived from the original on 26 August 2024.

- ^ "RSPCA 2012 Annual Review". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Contact your local RSPCA animal rescue centre, hospital or shop | RSPCA". rspca.org.uk.

- ^ a b "Site closures and alternate services". RSPCA. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020.

- ^ "Facts and figures - RSPCA". Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ "Contact us". RSPCA.

- ^ Ricketts, Andy (3 May 2018). "Chris Sherwood appointed chief executive of the RSPCA". Third Sector. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ^ "Job vacancies | rspca.org.uk". rspca.org.uk.

- ^ Vídeo de cão sendo espancado gera prisão de agressor, Yahoo!, RSPCA

- ^ Baker, Rosie (10 May 2012). "RSPCA launches first charity mobile network". Marketing Week. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ Pudelek, Jenna (11 May 2012). "RSPCA launches mobile phone service that will raise funds". Third Sector. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ See Metropolitan Police Act 1829

- ^ See Police uniforms and equipment in the United Kingdom

- ^ a b c d "Invasion of privacy". The Sunday Times. London. 3 June 2007. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2013. (registration required)

- ^ Sharma, Sonia (21 May 2012). "Stanley woman found guilty of mistreating dog". Chronicle Live (UK). South Tyneside. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "Animal Welfare Act 2006".

- ^ "ARCHIVE: Defra, UK – Animal Health and Welfare – Animal Welfare – Animal Welfare Act". Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- ^ "Richard Martin - Freedom of Information requests". WhatDoTheyKnow. 2 July 2013.

- ^ "RSPCA access to PNC records". Association of Chief Police Officers. 2 August 2013. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013.

- ^ a b c "Horse-Slaughtering Film Controversy". The Birmingham Post. 25 November 1925. p. 9. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e "The Horse Film: R.S.P.C.A. Reply to the Faking Charge". The Nottingham Evening Post. 1 December 1925. p. 7. (subscription required)

- ^ a b "R.S.P.C.A. Deny Charge of Film Faking". Westminster Gazette. 26 October 1925. p. 3. (subscription required)

- ^ a b "Captain Gee, V.C. and the R.S.P.C.A." The Yorkshire Post. 24 November 1925. p. 10. (subscription required)

- ^ "The Traffic in Worn-Out Horses". October 28, 1925. p. 784. (subscription required)

- ^ a b "Export of Horses to the Continent". The Derby Daily Telegraph. 28 October 1925. p. 4. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f "Film of Cruelty to Horses Arouses Hysteria". The Leeds Mercury. 24 November 1925. p. 1. (subscription required)

- ^ "Stabbed Horses". The Daily News. 23 November 1925. p. 5. (subscription required)

- ^ a b "R.S.P.C.A. Film: Further Reply to the Faking Allegation". The Daily Herald. 28 October 1925. p. 5. (subscription required)

- ^ "The R.S.P.C.A. Faked Film". The Daily News. 20 November 1925. p. 4. (subscription required)

- ^ a b "R.S.P.C.A and V.C." Hampshire Telegraph and Post. 22 January 1926. p. 15. (subscription required)

- ^ "Captain Gee, M. P. Writ for Slander Issued by the R.S.P.C.A." Midland Counties Tribune and Warwickshire County Graphic. 22 January 1926. p. 8. (subscription required)

- ^ "What is RSPCA Assured?". RSPCA Assured. 2024.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". RSPCA Assured. 2024. Archived from the original on 26 August 2024.

- ^ Monbiot, George (18 June 2024). "How Britain's oldest animal welfare charity became a byword for cruelty on an industrial scale". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ Gadher, Dipesh (9 June 2024). "Chris Packham: The truth at some RSPCA-assured farms makes me sick". The Times. Archived from the original on 9 June 2024.

- ^ "Investigation into the RSPCA Assured scheme reveals widespread animal suffering". ethicalglobe.com. Ethical Globe Project Ltd. 16 June 2024. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ a b Animal groups in bitter cash row BBC News, 3 January 2009

- ^ "New identity for animal charity". BBC News. 1 August 2005.

- ^ Copping, Jasper (12 March 2006). "Back off Badgers campaign". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ "RSPCA badger cull 'extermination' advert deemed misleading by ASA". 26 October 2013. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014.

- ^ "RSPCA anti badger cull advert banned". BBC News. 11 December 2013.

- ^ Sawer, Patrick (14 September 2013). "RSPCA deputy leader warns 'too political' campaigns threaten charity's future". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 15 September 2013.

- ^ Bingham, John (16 September 2013). "RSPCA fears exodus of 'disillusioned staff', says deputy chairman". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "'Livestock suffer like Jews in the Holocaust' says RSPCA ruling council candidate Peta Watson-Smith, from Lincolnshire". Lincolnshire Echo.

- ^ Mendick, Robert (13 May 2016). "RSPCA boss says sorry for blunders and admits charity was too political". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "RSPCA to become 'less adversarial' under new boss". BBC. 14 May 2016.

- ^ Midgley, Olivia (20 June 2017). "'Utterly dysfunctional' - RSPCA under attack again after resignation of chief executive". Farmers Guardian.

- ^ Siddique, Haroon (14 April 2019). "RSPCA faces fraud investigation at south-east London branch". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ a b Sawer, Patrick; Wallis, Lynne (3 November 2013). "RSPCA accused of persecuting owners of animal shelters". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017.

- ^ "Our policies". RSPCA.

- ^ Dugan, Emily (29 March 2008). "Hindu monks sue RSPCA over slaughter of sacred cow Gangotri". The Independent. London.

- ^ Pigott, Robert (12 December 2008). "RSPCA sorry for killing sacred cow". BBC News.

- ^ "Mr Richard and Mrs Samantha Byrnes – an Apology". RSPCA News. 5 November 2014. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014.

- ^ Kennedy, Dominic (28 March 2016). "Secret report shows RSPCA's cruel dishonesty". The Times. Archived from the original on 4 September 2024. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ Roberts, Elizabeth (13 September 2015). "RSPCA euthanising healthy horses as cases of neglect hit crisis point". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Dixon, Hayley (14 May 2013). "RSPCA whistleblower found hanged". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Tory MP: RSPCA Heythrop Hunt prosecution has a 'strong political edge'". civilsociety.co.uk.

- ^ Waite, John (7 August 2013). "The RSPCA – A law unto itself?". Face the Facts. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ Kennedy, Dominic (7 August 2013). "RSPCA tried to discredit expert who gave evidence against charity". The Times. Archived from the original on 4 September 2024. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "Claims made about the RSPCA in R4 'Face the Facts' & our answers". RSPCA. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014.

- ^ "RSPCA statement on allegations by British Association of No Kill Sanctuaries (BANKS)". RSPCA. 3 November 2013. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014.

- ^ "Address serious governance failures, RSPCA leaders are warned". Government of the United Kingdom. 10 November 2023.

- ^ "The Earl of Harrowby". The Grantham Journal. 25 November 1882. p. 3. (subscription required)

- ^ a b Preece, Rod. (2011). Animal Sensibility and Inclusive Justice in the Age of Bernard Shaw. p. 118. ISBN 978-0774821124

- ^ a b Fairholme, Edward G. (1924). A Century of Work for Animals: The History of the R.S.P.C.A., 1824-1924. E. P. Dutton. p. 101

- ^ "Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals". The Graphic Christmas Number. 1910. p. 34. (subscription required)

- ^ "Ninetieth Annual Report, 1913". Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. 1913.

- ^ "The Prince of Wales". The Yorkshire Post. 31 May 1919. p. 11. (subscription required)

- ^ "The First Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals". The National Humane Review. 11 (2): 35. 1923.

- ^ "R.S.P.C.A. Posts". The Liverpool Post. 19 June 1951. p. 3. (subscription required)

- ^ "Sir Malcolm Sargent is new president of R.S.P.C.A." Belfast News-Letter. 7 February 1958. p. 4. (subscription required)

- ^ "Sir Malcolm Sargent R.S.P.C.A. President". The Scotsman. 7 February 1958. p. 1. (subscription required)

- ^ Hursthouse, Rosalind (2000). Ethics, Humans and Other Animals: An Introduction with Readings. Routledge. p. 236. ISBN 978-0415212427.

- ^ Batty, David (2016). "Richard Adams, Watership Down author, dies aged 96". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 January 2024.

- ^ "TRUSTEES' REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2019". rspca.org.uk. 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Bonner, Tim (2023). "Chris Packham, the RSPCA and animal rights". Countryside Alliance. Archived from the original on 6 August 2024.

- ^ "RSPCA announces Chris Packham as President". RSPCA. 2023. Archived from the original on 14 June 2024.

- ^ "RSPCA: Chris Packham and Caroline Lucas quit charity over abattoir cruelty claims". BBC News. 21 December 2024. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ Detail from a copy of the book, published by Heinemann of London in 1974 with an ISBN of 434 90189 X. The chapters relate to the origin of the society, and finishes with prospects for the future, with a foreword by John Hobhouse (chairman of the RSPCA).

Further reading Kew, Barry (2023). Lewis Gompertz: Philosopher, Activist, Philanthropist, Inventor. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-6667-6129-0.

External links

[edit]- RSPCA

- 1824 establishments in the United Kingdom

- Animal charities based in the United Kingdom

- Animal welfare organisations based in the United Kingdom

- Organisations based in the United Kingdom with royal patronage

- Organisations based in West Sussex

- Organizations established in 1824

- Royal charities of the United Kingdom