International adoption of South Korean children

Adoptions from South Korea Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

1950 — – 1960 — – 1970 — – 1980 — – 1990 — – 2000 — – 2010 — – 2020 — |

| |||||||||||||||||

Source: Ministry of Health and Welfare (1968, 2005, 2023) | ||||||||||||||||||

The international adoption of South Korean children started around 1953 as a measure to take care of the large number of mixed children that became orphaned during and after the Korean War. It quickly evolved to include orphaned Korean children. Religious organizations in the United States, Australia, and many Western European nations slowly developed the apparatus that sustained international adoption as a socially integrated system.

From the 1970s through the 2000s, thousands of children were adopted overseas every year. Over time, the South Korean government has sought to decrease international adoptions in favor of domestic adoptions. In 2023, seventy years after its start, South Korea still sent 79 children overseas, making it the longest-running international adoption program in the world.[5]

Korean War and Holt

[edit]Korean War

[edit]A 1988 article which was originally printed in The Progressive and was later reprinted in Pound Pup Legacy stated that less than one percent of Korean adoptees who are currently adopted are Amerasian, but during the decade after the Korean War, most of the Korean adoptees were Amerasians who were fathered by American soldiers.[6]

Albert C. Gaw (1993) stated that 6,293 Koreans were adopted in the United States between 1955 and 1966, of whom about 46% were white and Korean mixed, 41% were fully Korean, and the rest were African-American and Korean mixed.[7] The first wave of adopted people from Korea came from usually mixed-race children whose families lived in poverty; the children's parents were often American military men and Korean women.[8]

A 2015 article which was printed in Public Radio International stated that Arissa Oh who wrote a book about the beginnings of international adoption said that "Koreans have this myth of racial purity; they wanted to get rid of these children. Originally international adoption was supposed to be this race-based evacuation."[9]

Holt

[edit]The start of adoption in South Korea is usually credited to Harry Holt in 1955.[10][8] Harry Holt wanted to help the children of South Korea,[11] so Holt adopted eight children from South Korea and brought them home. In part due to the response that Holt got after adopting these eight children from the nationwide press coverage, Holt started Holt International Children's Services, which is an adoption agency based in the United States which specialized in finding families for Korean children.[8]

Touched by the fate of the orphans, Western religious groups as well as other associations started the process of placing children in homes in the United States and Europe. Adoption from South Korea began in 1955 when Bertha and Harry Holt went to Korea and adopted eight war orphans after passing a law through Congress.[6] Their work resulted in the founding of Holt International Children's Services. The first Korean babies sent to Europe went to Sweden via the Social Welfare Society in the mid-1960s. By the end of that decade, the Holt International Children's Services began sending Korean orphans to Norway, Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Switzerland, and Germany.

Media coverage of adoption

[edit]South Korean media coverage

[edit]In 1988, when South Korea hosted the 1988 Summer Olympics, the international adoption of South Korean children became the focus of global attention, and the issue became a source of national humiliation for South Korea. Politicians claimed that they would try to stop "child exports", so they set an intended end date and a quota for international adoptions. However, the quota has been exceeded several times, and the intended end date has been extended several times.[2]

Not until the 1980s and early 1990s did the South Korean government and South Koreans, both in South Korea and in the diaspora, pay any significant attention to the fates of Korean adoptees. The nation was not prepared for the return of their 'lost children.' But the numerous adult Korean adoptees who visited Korea as tourists every year, in addition to raising public awareness of the Korean adoptee diaspora, forced Korea to face a shameful and largely unknown part of their history. South Korean president Kim Dae-jung invited 29 adult Korean adoptees from 8 countries to a personal meeting in the Blue House in October 1998. During this meeting he publicly apologized for South Korea's inability to raise them.[12]

It's been eight months since I became President. During this period, I've met countless people. But today's meeting with all of you is personally the most meaningful and moving encounter for me. Looking at you, I am proud of such accomplished adults, but I am also overwhelmed with an enormous sense of regret at all the pain that you must have been subjected to. Some 200,000 Korean children have been adopted to the United States, Canada, and many European countries over the years. I am pained to think that we could not raise you ourselves, and had to give you away for foreign adoption.

— Kim Dae-jung, Kim Dae-jung's Apology to 29 Korean Adoptees in 1998, Yngvesson (2010)[13]

Since then, South Korean media rather frequently reports on the issues regarding international adoption. Most Korean adoptees have taken on the citizenship of their adoptive country and no longer have Korean passports. Earlier they had to get a visa like any other foreigner if they wanted to visit or live in South Korea. This only added to the feeling that they were "not really South Korean". In May 1999, a group of Korean adoptees living in Korea started a signature-collection in order to achieve legal recognition and acceptance (Schuhmacher, 1999). At present (2009) the number of Korean adoptees long-term residents in South Korea (mainly Seoul) is estimated at 500. It is not unlikely that this number will increase in the following decade (International adoption from South Korea peaked in the mid-1980s). A report from Global Overseas Adoptees' Link (G.O.A.'L) indicates that the long term returnees (more than one year) are predominantly in their early twenties or early thirties.

One factor that helped make the subject of Korean adoptees part of the South Korean discourse was a 1991 film called Susanne Brink's Arirang which was a film about the life story of a Korean adoptee who grew up in Sweden. This film made the subject of the international adoptions of Korean children a hot topic in South Korea, and it made South Koreans feel shame and guilt regarding the issue.[2]

A 1997 article in The Christian Science Monitor said that Koreans in South Korea often believed that adoptive families in other countries had ulterior motives for adopting Korean orphans due to the Korean belief that parents can not love a child who is not their biological child.[14] [15][16][17]

North Korean media coverage

[edit]A 1988 article which was originally in The Progressive and reprinted in Pound Pup Legacy said that the director general of South Korea's Bureau of Family Affairs in the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs said that the large number of international adoptions out of South Korea had been an issue used as part of North Korea's propaganda against South Korea in the 1970s. As part of North Korea's propaganda against South Korea in the 1970s, North Korea decried the large numbers of international adoptions of South Korean children, and North Korea decried what it considered to be South Korea's practice of selling South Korean children. The South Korean director general wanted to decrease the numbers of South Korean children being adopted internationally, so North Korea would no longer have the issue to use for its propaganda against South Korea. The news article also said that North Korea did not allow couples in other countries to adopt North Korean children.[6]

The 1988 article was serialized by The People's Korea, a pro-North Korea magazine, and the resulting publicity caused South Korea to have the image in the North as the number one child-exporting country of the world:[18] The Pyongyang Times, a North Korean newspaper, printed: "The traitors of South Korea, old hands at treacheries, are selling thousands, tens of thousands of children going ragged and hungry to foreign marauders under the name of 'adopted children'."[18]

Korean patrilineal blood culture

[edit]A 1988 article which was originally in The Progressive and reprinted in Pound Pup Legacy said that South Korean culture is a patrilineal culture that places importance on families related by blood. The importance of bloodline families is the reason why Koreans do not want to adopt Korean orphans, because the Korean adoptee would not be the blood relative of the adoptive parents. Korean patrilineal culture is the reason Korean society stigmatizes and discriminates against unwed Korean mothers and their kids, making it so the unwed mother might not be able to get a job or get a husband.[6]

A 2007 doctoral dissertation by Sue-Je Lee Gage in the Department of Anthropology at Indiana University states that in Korean patrilineal blood culture, Koreanness is passed from parent to child as long as the parents have "pure" Korean blood, and this transference of Koreanness is especially notable when the Korean father gives his "pure" Korean blood to his Korean child, making lineage along the father's line especially important in the Korean concept of race and identity. Gage said that a Korean family's lineage history represents the official recording of their blood purity. Due to this conception of identity along blood lines and race, Gage said that Koreans in South Korea consider Korean adoptees who return to South Korea to still be Korean even if they cannot speak Korean. Gage said that, for Koreans, a Korean physical appearance is the most important consideration when identifying other people as being Koreans, although a Korean physical appearance is not the only consideration Koreans use in their consideration for group membership as a fellow Korean. For example, Gage said that Korean women who had sex with non-Korean men were often not considered to be "Korean" in the "full-fledged" sense by Koreans.[19]

The Fall 2012 journal of The Journal of Korean Studies said that anthropologist Elise Prebin said that Korean adoptee reunions can be more secure and are easier maintained along the birth father's line (patrilineal) than along the birth mother's line (matrilineal) in her study of Korean adoptee reunions with birth families. The journal said that "Korean patrilineal kinship ideologies" still have a strong societal influence in South Korea.[20]

A 2014 article in NPR said that unwed mothers suffer a social stigma in South Korea, because having a child out of wedlock is an act that goes against Korean patrilineal bloodline culture. The 2014 news article also said that Korean adoptees suffer a social stigma in South Korea, because Korean adoptees have been "cut loose from their bloodlines".[21]

A 2015 news article said that there is still a strong social stigma against unwed mothers and illegitimate children in South Korea. The 2015 news article said that this social stigma applies to the unwed mother and even her illegitimate children and her whole extended family, causing a child who was born out of wedlock to suffer lowered marital, job and educational prospects in South Korea.[22]

A 2015 article in The Economist said that Koreans in South Korea mostly adopt female Korean children to avoid issues involving ancestral family rites which are usually done by bloodline sons and to avoid issues involving inheritance.[23]

Economics

[edit]Costs saved by South Korea

[edit]A 1988 article which was originally in The Progressive and reprinted in Pound Pup Legacy said that the South Korean government made fifteen to twenty million dollars per year by the adoption of Korean orphans by families in other countries. The 1988 news article also said that the adoption of Korean orphans out of South Korea had three more effects: it saved the South Korean government the costs of caring for the Korean orphans, it relieved the South Korean government of the need to figure out what to do with the orphans and it lowered the population.[6]

Some academics and researchers claim that the system for orphans Korean adoption agencies have established guarantee a steady supply of healthy children.[24][better source needed] Supporters of the system claim that adoption agencies are only caring for infants who would otherwise go homeless or be institutionalized.

Korean adoption agencies support pregnant-women's homes; three of the four agencies run their own. One of the agencies has its own maternity hospital and does its own delivery. All four provide and subsidize child care. All pay foster mothers a monthly stipend to care for the infants, and the agencies provide all food, clothing and other supplies free of charge. They also support both independent-orphanages, and or self-run ones. The agencies will cover the costs of delivery and the medical care for any woman who gives up her baby for adoption (Rothschild, The Progressive, 1988; Schwekendiek, 2012).

A 2011 article in the Institute for Policy Studies estimated each adoption cost US$15k, paid primarily by the adopting parents. This generated an estimated US$35M/yr to cover foster-care, medical care, and other costs for the approximately 2,300 Korean international adoptions.[25]

Social welfare of South Korea

[edit]In a 2010 book, Kim Rasmussen said that the "root cause" of the number of adoptions out of South Korea in 2010 was South Korea's lack of spending on its social welfare system. Rasmussen said that the other OECD-30 countries spent an average of 20.6% of their GDP on social welfare benefits while South Korea only spent 6.9% of its GDP on social welfare benefits. Rasmussen said that South Korea promoting domestic adoption would not address the heart of the problem and that South Korea should raise its spending for social welfare benefits.[26]

Birth mothers and orphans

[edit]Birth mothers

[edit]In the 1988 article which was originally in The Progressive and reprinted in Pound Pup Legacy, a South Korean orphanage director said that according to his orphanage's questionnaire data 90% of Korean birth mothers indicated that wanted to keep their biological child and not give them up for adoption, but the South Korean orphanage director said that only maybe 10% of birth mothers eventually decided to keep their biological child after his orphanage suggested to the birth mothers that unwed mothers and poor couples should give their child up for adoption. The 1988 news article said that the Korean birth mothers felt guilty after giving their child up for adoption, and it said that most of the Korean birth mothers who gave their child up for adoption were poor and worked at factory or clerical jobs in South Korea.[6]

In a same 1988 article, an INS officer at the Embassy of the United States, Seoul, said that social workers were hired by adoption agencies to perform the role of "heavies" to convince South Korean mothers to give their children up for adoption. Although the officer said that he felt that the adoption business was probably a good thing for birth mothers, adoptive parents and adoptees, he said that the adoption business troubled him due to the large number of children who were being adopted out of South Korea every month. The INS officer said that these numbers should make people question how much of the international adoption of South Korean children was a humanitarian cause and how much it was a business.[6][27]

Orphans

[edit]A 2014 article in NPR said that it was "effectively impossible" for Korean orphans who aged out of institutions at 18 years old to attend a university in South Korea due to lacking the money to pay for all of the associated costs, so most Korean orphans ended up getting low-paying jobs in South Korean factories after aging out of the institutions. The 2014 news article said that many Korean parents in South Korea refuse to allow their children to marry Korean orphans.[21]

A 2015 article said that the majority of South Korean orphans become orphans at a young age, and the 2015 article said that the majority of South Korean orphans eventually age out of the orphanages' care when they turn 18 years old never being adopted.[28]

A 2015 article in The Economist said that in the past 60 years two million or about 85% of the total orphans in South Korea have grown up in South Korean orphanages never being adopted. The 2015 article said that from the 1950s to 2015 only 4% of the total number of orphans in South Korea had been adopted domestically by other Koreans in South Korea.[23]

A 2015 video by BBC News said that orphanages in South Korea had become full as a result of the South Korean government making it more difficult for Korean orphans to be adopted overseas.[29]

Baby box

[edit]In a video which was published on March 27, 2014, on the France 24 YouTube channel, Ross Oke, the international coordinator of Truth and Reconciliation for the Adoption Community of Korea (TRACK), said that baby boxes like the one in South Korea encourage abandonment of children and they deny the abandoned child the right to an identity.[30]

A 2015 article in Special Broadcasting Service said that in 2009 South Korean pastor Lee Jong-rak put a "baby box" on his church in Seoul, South Korea, to allow people to anonymously abandon children. The article said that since the abandoned children have not been formally relinquished, they cannot be adopted internationally. The article said that the children will most likely stay in orphanages until they become 18 or 19 years old.[31]

Korean Adoption Services database

[edit]A 2014 article in The Korea Herald said that the Korea Adoption Services was digitizing 35,000 documents regarding international adoptions that took place in South Korea since the 1950s to further the efforts of Korean adoptees locating their birth parents.[32]

A 2017 article in The Hankyoreh said that Seo Jae-song and his wife who used to run the Seonggajeong orphanage in Deokjeokdo and later the St. Vincent Home in Bupyeong District had 1,073 Korean adoption records. In 2016, these 1,073 Korean adoption records were scanned by Korean Adoption Services (KAS) and the Ministry of Health and Welfare. In 2016, KAS had 39,000 records from 21 institutions.[33]

Korea's domestic adoptions

[edit]A 2015 article said that the South Korean government is trying to have more domestic adoptions due, in part, to people around the world becoming aware of the large number of Korean adoptees who were adopted by families outside of South Korea since the mid-1950s. Because the South Korean government does not want to have the reputation of a "baby-exporting country", and due to the belief that Koreans should be raised with Korean culture, the South Korean government has been trying to increase domestic adoptions.[28] However, this has been less than successful over the decades. The numbers only picked up after 2007.[34]

However, the numbers of domestic adoption fell in 2013 due to tighter restrictions on eligibility for adoptive parents. The number in babies has also gone up with the forced registration of babies, also a new law, leading to more abandonment.[35]

The primary reason as of 2015 for the majority of surrenders within South Korea is single mothers are still publicly shamed within Korea,[36][37] and the South Korean mothers who give their kids up for adoption have been mostly middle or working-class women since the 1990s.[1] The amount of money single mothers can receive within the country is 70,000 won per month, only after proving poverty versus the tax break from adopting domestically is 150,000 won per month, which is unconditional, whereas it's conditional in the case of single mothers.[36] 33 facilities for single and divorced mothers, but the majority of them are run by orphanages and adoption agencies.

In a 2009 article, Stephen C. Morrison, a Korean adoptee, said that he wanted more Koreans to be willing to adopt Korean children. Morrison said that he felt the practice of Koreans adopting Korean children in secret was the greatest obstacle for Korean acceptance of domestic adoption. Morrison also said that in order for domestic Korean adoption to be accepted by Koreans he felt that Korean people's attitudes must change, so that Koreans show respect for Korean adoptees, not speak of Korean adoptees as "exported items" and not refer to Korean adoptees using unpleasant expressions of which Morrison gave the example, "a thing picked up from under a bridge". Morrison said that he felt that the South Korean government should raise the allowable age at which Korean parents could adopt Korean orphans and raise the allowable age at which Korean orphans could be adopted by Korean parents, since both of these changes would allow for more domestic adoptions.[38]

Even in its capacity as a global economy and OECD nation, Korea still sends children abroad for international adoption. The proportion of children leaving Korea for adoption amounted to about 1% of its live births for several years during the 1980s (Kane, 1993); currently, even with a large drop in the Korean birth rate to below 1.2 children per woman and an increasingly wealthy economy, about 0.5% (1 in 200) of Korean children are still sent to other countries every year.[citation needed]

A 2005 opinion piece in The Chosun Ilbo said that South Korean actress Shin Ae-ra and South Korean actor Cha In-pyo publicly adopted a Korean daughter after already having a biological son together, and the article said that by publicly adopting a Korean orphan this the couple could cause other Koreans to change their views about domestic adoptions in South Korea.[39]

Quota for overseas adoptions

[edit]To stem the number of overseas adoptions, the South Korean government introduced a quota system for foreign adoptions in 1987. Under this system, the nation reduced the number of children permitted for overseas adoption by 3 to 5% each year, from about 8,000 in 1987 to 2,057 in 1997. The goal of the plan was to eliminate foreign adoptions by 2015. But in 1998 the government temporarily lifted the restrictions, after the number of abandoned children sharply increased in the wake of growing economic hardships.

Notable is a focused effort of the 2009 South Korean government to seize international adoption out of South Korea, with the establishment of KCare and the domestic Adoption Promotion Law.

Incentivizing domestic adoptions

[edit]A 1997 article in The Christian Science Monitor said that South Korea was giving incentives in the form of housing, medical and educational subsidies to Korean couples who adopted Korean orphans to help encourage domestic adoption, but the Korean couples in South Korea who did adopt tended to not use these subsidies, because they did not want other Koreans knowing that their children were not their biological children.[14]

Special Adoption Law

[edit]A 2013 article in CNN said that Jane Jeong Trenka who is a Korean adoptee along with others came up with the Special Adoption Law. The article said that the Special Adoption Law would make it so birth mothers have to stay with their child for seven days before giving it up for adoption. The article said that the Special Adoption Law would make it so the birth mothers' consent has to be verified before relinquishment of their child, and the article said that Special Adoption Law would make it so the birth of the child is registered. The article said that the Special Adoption Law would also make it so the birth mother could retract her relinquishment for up to six months following her application. The article said that Steve Choi Morrison who is a Korean adoptee and founder of Mission to Promote Adoption in Korea (MPAK) fought against the Special Adoption Law. The article said that Morrison was against the Special Adoption Law because Morrison said that Korean culture is a culture where saving face is important. The article said that Morrison said that Korean birth mothers would fear the record of the birth becoming known, and men will not marry them afterwards. The article said that Morrison predicted that forcing Korean birth mothers to register the births would lead to abandonments.[40]

A 2015 article in the Washington International Law Journal suggested that the Special Adoption Act may have been a factor in more babies being abandoned after the enactment of the Special Adoption Act on August 5, 2012.[41]

Revised Special Adoption Act

[edit]The Revised Special Adoption Act which was enacted in South Korea in 2012 made domestic adoptions in South Korea recorded as the biological children of the Korean adoptive parents.[42]

A 2014 article in NPR said that the Revised Special Adoption Law did not make adopting Korean children equal to adding a blood relative in the minds of Koreans regardless of how domestic Korean adoptions would now be considered for legal purposes.[21]

Countries which Korean adoptees were sent to

[edit]| States which most Korean adoptees were sent to |

|---|

Source: Kim (2010)[1]

|

| Cities with many Korean adoptee residents, Europe |

Source: Kim (2010)[1]

|

| Cities with many Korean adoptee residents, United States |

Source: Kim (2010)[1]

|

A 2010 book about Korean adoption said that there are Korean adoptee groups in cities that are in areas with many Korean adoptees residents such as in Stockholm, Copenhagen, Oslo, Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam, New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Minneapolis, Seattle, Portland, Chicago, Boston, and Seoul.[1]

Adoptees in the United States

[edit]An archived web page of the Bureau of Consular Affairs website that said that it was last updated in 2009 said that US couples who wanted to adopt Korean children needed to meet certain requirements. The web page said that the couples needed to be between 25 and 44 years old with an age difference between spouses of no more than 15 years, the couples needed to be married for three years, the couples needed to have an income higher than the US national average, and the couples could not already have more than five children. The web page said that US couples had to pay a fee between $9,500 and $10,000 to adopt a Korean child, and the web page said that it took one to four years after applying for the adopted Korean child to arrive in the United States. The web page said that the wait time after applying for US couples who wanted to adopt was about three years for a healthy Korean child and one year for a Korean child with special needs.[43]

A 1988 article originally published in The Progressive and reprinted in Pound Pup Legacy said that there were 2,000,000 couples who wanted to adopt children in the United States, but only 20,000 healthy children were available for domestic adoption in the United States. The 1988 news article said that the lack of children for domestic adoption caused couples in the United States to look to other countries to adopt children, and the fastest increase of American couples' adoptions from other countries at this time was from South Korea.[6]

A 2010 book about Korean adoption said that Korean adoptees comprise about ten percent of the total Korean American population according to an estimate in a 2010 book about South Korean adoption. The book said that, in the United States, the majority of Korean adoptees were adopted close to adoption agencies, so they were mostly adopted in the states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Nebraska, Michigan, Montana, South Dakota, Oregon, Washington, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Vermont, Utah or Idaho.[1]

Adoptees in Sweden

[edit]A 2002 article in the Embassy of Sweden, Seoul, said that due to the Swedish welfare state of the 1960s more Swedish families started adopting Korean children. The article said that the Swedish welfare system allowed for unwed Swedish mothers to better support themselves and not feel the need to give up their children for adoption. The article said that, as a consequence, there were fewer Swedish orphans in Sweden for domestic adoptions, so Swedish families who wanted to adopt children had to adopt from other countries. The article said that the reason for Korean adoptions, specifically, was that some Swedish families had already adopted Koreans in the 1950s, so later families continued this trend.[44]

Psychological effects

[edit]Perception of who the adoptees' "real" parents are

[edit]In a 2016 study of 16 Korean American transnational adult adoptees, some of the Korean adoptees viewed their adoptive parents as their "real" parents and some viewed their biological parents as their "real" parents.[45]

Pronunciation of Korean

[edit]A 2017 article in BBC News said that an article published in Royal Society Open Science said that Dutch-speaking Korean adoptees who were retrained in the Korean language were able to pronounce Korean better than expectations. Korean adoptees who were about 30 years old and who were adopted as babies to Dutch-speaking families were used in the study. The Korean adoptees were compared to a group of adults who had not been exposed to Korean as children. Following a short training course, the Korean adoptees were asked to pronounce Korean consonants for the study. The Korean adoptees did better than expectations after training.[46]

Sex work

[edit]In her Ph.D. thesis, Sarah Y. Park cited Kendall (2005) and Kim (2007) when Park said that female Korean adoptees are commonly told that they may have become a prostitute if they were not adopted out of Korea.[47]

Social problems

[edit]A 2002 study in The Lancet of intercountry adoptees in Sweden of various ethnic backgrounds, most of whom were of Korean, Colombian or Indian (from India) extraction, who were adopted by two parents who were born in Sweden found that intercountry adoptees had the following increased likelihoods relative to the rest of the children who were born in Sweden to two parents who were themselves also born in Sweden: intercountry adoptees were 3.6 times more likely to die from suicide, 3.6 times more likely to attempt suicide, 3.2 times more likely to be admitted for a psychological disorder, 5.2 times more likely to abuse drugs, 2.6 times more likely to abuse alcohol and 1.6 times more likely to commit a crime.[48]

Abandonment

[edit]A 2006 article in New America Media said that an increasing number of South Korean parents were paying elderly American couples to adopt their children for the purpose of having their child receive US education and US citizenship. However, the article said that according to Peter Chang, who led the Korean Family Center in Los Angeles, Korean children who were put up for adoption for the purpose of receiving US education and US citizenship frequently felt betrayed by their biological parents. The article said that getting US citizenship this way required the adopted child to be adopted before their sixteenth birthday and stay with their adoptive family for at least two years.[49]

In a 1999 study of 167 adult Korean adoptees by The Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, the majority of the adult Korean adoptees struggled with the thought of how their birth mother could have given them up for adoption.[50]

Korean culture socialization

[edit]A 2012 study in the Journal of Adolescent Research of Korean adoptees in the United States found that white parents of Korean adoptees whose average age was 17.8 years old tended to try to socialize their adopted Korean children to Korean culture by doing overt actions such as going to Korean restaurants or having them attend Korean culture camp rather than having conversations with them about Korean ethnic identity or being a racial minority in the United States. The study said that for many families doing these overt actions was easier and more comfortable for them than discussing the personal issues of ethnic identity or being a racial minority in the United States.[51]

In a 2005 article, a 38-year-old Korean adoptee who was adopted in the United States said that social workers told her adoptive parents to not raise her with ties to South Korea, because the social workers said that doing that would confuse her. The 2005 article said that adoptive parents were no longer trying to cut ties with the culture of their adopted child's birth country as of 2005, and adoptive parents were instead trying to introduce their adopted kid to the culture of their birth country. In 2005, one popular way for adoptive parents to expose their adopted child to the traditions and food of their birth country was for them to attend "culture camps" which would last for one day.[52]

Cross-race effect

[edit]A 2005 study in American Psychological Society of the cross-race effect used Korean adoptees whose average age was 27.8 years old who were adopted when they were between 3 and 9 years old by French families and the study also used recent Korean immigrants to France. The study had the participants briefly see a photograph of a Caucasian or Japanese face, then the participants had to try to recognize the same Caucasian or Japanese face which they had just seen from a pair of either Caucasian or Japanese faces. The Korean adoptees and French people could recognize the Caucasian faces better than they could recognize the Japanese faces, but the recent Korean immigrants could recognize the Japanese faces better than they could recognize the Caucasian faces, suggesting that the cross-race effect can be modified based on familiarity with certain types of faces due to experiences starting after three years of age.[53]

Implicitly raised as white

[edit]C. N. Le, a lecturer at the sociology department at the University of Massachusetts Amherst,[54] said that Korean adoptees and non-white adoptees in general who are raised by white families are raised to implicitly think that they are white, but since they are not white, there is a disconnect between the way they are socialized at home and the way the rest of society sees them. Le further said that most white families of non-white adoptees are not comfortable talking with their adopted children about the issues that racial minorities face in the United States, and Le further advised white families who adopt transracially that just introducing their kids to Asian culture, telling them that race is not important and/or telling them that people should get equal treatment in society is insufficient. Le said that the social disconnection between how they were raised and the reality of American society causes "confusion, resentment about their situation, and anger" for adoptees who were transracially adopted by white families.[55]

Many of the South Korean children adopted internationally grew up in white, upper or middle-class homes. In the beginning adoptive families were often told by agencies and social workers to assimilate their children and make them as much as possible a part of the new culture, thinking that this would override concerns about ethnic identity and origin. Many Korean adoptees grew up not knowing about other children like themselves.[56] This has changed in recent years with social services now encouraging parents and using home studies to encourage prospective adoptive parents to learn about the cultural influences of the country. With such works as "Beyond Culture Camp"[57] which encourage the teaching of culture, there has been a large shift. Though, these materials may be given, not everyone may take advantage of them. Also, adoption agencies started to allow the adoption of South Koreans by people of color in the late 1990s to early 2000, and not just white people, including Korean-Americans. Such an example of this is the rapper GOWE, who was adopted by a Chinese-American family.

As a result of many internationally adopted Korean adoptees growing up in white areas, many of these adoptees avoided other Asians in childhood and adolescence out of an unfamiliarity and/or discomfort with Asian cultures.[58][not specific enough to verify] These adoptees sometimes express a desire to be white like their families and peers, and strongly identify with white society. As a result, meeting South Koreans and Korean culture might have been a traumatic experience for some.[56] However, other Korean adoptees, often those raised in racially or culturally diverse communities, grew up with ties to the Korean community and identify more strongly with the Korean aspect of their identities.[58] [59]

Adoptees' feelings about South Korea

[edit]In a 1999 study of 167 adult Korean adoptees by The Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, group discussions about the topic of how they felt about South Korea led to many feelings. There was anger about the negative way Koreans view adopted Koreans. There was concern over Korean orphans in South Korean orphanages, and there was a feeling of obligation to help the Korean orphans who remained in the South Korean orphanages. There was a feeling of responsibility to change Koreans' views of domestic adoption, so that adopting an orphan in South Korea would not be something that Koreans in South Korea would be ashamed of doing.[50]

Adoptees' memories of orphanages and initial adoption

[edit]In a 1999 study of 167 adult Korean adoptees by The Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, there were adoptees who mainly remembered experiencing poverty as orphans such as one adoptee who remembered eating much oatmeal with flies in it as an orphan in South Korea. Some adoptees remembered feeling a sense of loss of the relationships that they had with people when they left their South Korean orphanages. Some of the adoptees remembered being scared of their new living situation with adoptive parents in a new country when they had just been adopted out of South Korea.[50]

Discrimination

[edit]Discrimination for being adopted

[edit]A 2014 article in NPR said that Koreans in South Korea were prejudiced against Korean adoptees, and the 2014 news article said that Korean adoptees who were adopted domestically by other Koreans in South Korea often became outcast and bullied by other Koreans at their South Korean school.[21]

Discrimination for race and appearance

[edit]In a 1999 study of 167 adult Korean adoptees by The Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, the majority of respondents (70%) reported their race being the reason they were discriminated against while growing up, and a minority of respondents (28%) reported their adoptee status as being the reason they were discriminated against while growing up. One of the study's respondents said that growing up in a small town of white people made him an oddity that few people wanted to associated with, and he said that he had wanted to be like other people instead of being different. Other respondents said that the discrimination they received growing up caused them to deny their Korean heritage.[50]

In a 2010 book, Kim Rasmussen gave an example of a Korean adoptee from the United States who returned to South Korea and tried to apply for the job of an English teacher in South Korea only to be denied the job due to her race. The Korean adoptee was told that she was rejected for the job, because the mothers of the students wanted their children to be taught English from a white person.[26]

In a 2015 article in The Straits Times, Korean adoptee Simone Huits who was adopted to a Dutch family in the Netherlands made the following remark about growing up in a small Dutch town, "All the children wanted to touch me because I looked different. It was scary and overwhelming."[60]

Discrimination for not speaking Korean

[edit]In a 1999 study of 167 adult Korean adoptees by The Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, the majority of respondents (72%) reported that they had no ability with the Korean language, and only a minority of respondents (25%) reported that they had any ability with the Korean language. Of the study's respondents who visited South Korea, 22% described their visit as a negative experience, and about 20% described their visit as a both negative and positive experience. Inability to speak Korean was mentioned as being a cause of their visit being a negative experience by more than one respondent, and inability to speak Korean was generally the cause of the negative parts of the visit for the respondents who reported both a positive and negative experience. One respondent said that they felt that Koreans in South Korea looked down on them for their inability to speak Korean. Another respondent said that the Koreans in South Korea were initially nice to them, but the respondent said that Koreans in South Korea became rude to them after finding out that they could not speak Korean. Many of the adoptees felt like they were foreigners while visiting South Korea.[50]

A 2007 book about Korean adoption said that it was uncomfortable for Korean adoptees who do not speak Korean and who do not have Korean last names to associate with Korean-speaking children of Korean immigrants in school districts with children of Korean immigrant families.[61]

Korean adoptee camps

[edit]| Holt International adoptee camp locations |

|---|

| Korean adoptee camp locations |

Holt adoptee camps

[edit]Holt adoptee camps are places where transracial and/or international adoptees can talk about feelings of not fitting in and isolation in a safe space. Each day there are group discussions about issues of identity, adoption and questions regarding race that last about an hour.[68] The locations of the camps are Corbett, Oregon; Williams Bay, Wisconsin; Ashland, Nebraska and Sussex, New Jersey.[62][63][64][65]

Camp Moo Gung Hwa

[edit]Camp Moo Gung Hwa is a Korean culture camp for Korean adoptees in Raleigh, North Carolina. The camp first started in 1995 with the name Camp Hodori, and the camp changed its name to Camp Moo Gung Hwa in 1996. The purpose of the camp is to improve the Korean adoptees' knowledge of Korean culture and improve their self-esteem.[69][non-primary source needed]

Korean Adoption Means Pride

[edit]Korean Adoption Means Pride (KAMP) is a camp in Dayton, Iowa for Korean adoptees and their families. The camp exposes camp attendees to Korean culture. Korean culture classes cover Korean cuisine, Korean dance, Korean language, taekwondo and Korean arts and crafts.[67][non-primary source needed]

Heritage Camps for Adoptive Families

[edit]Heritage Camps for Adoptive Families (HCAF) was founded in 1991 and consists of nine different camps for varying adoptee groups, one of which is Korean Heritage Camp.[70] KHC is held annually at Snow Mountain Ranch in Fraser, Colorado. It brings adoptees and their families together each year to learn about adoption and Korean culture.[71]

Adoptees returning to South Korea

[edit]Adoptees visiting South Korea

[edit]In a 1999 study of 167 adult Korean adoptees by The Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, most of the adult Korean adoptees felt that younger Korean adoptees should visit South Korea, 57% of the 167 adult Korean adoptees reported that they have visited South Korea and 38% of the 167 adult Korean adoptees reported visiting South Korea as a means with which they explored their Korean heritage.[50]

Eleana J. Kim, Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Rochester, said that South Korea developed programs for adult Korean adoptees to return to South Korea and learn about what it means to be Korean; these programs included wearing hanboks and learning to make kimchi.[72]

Adoptees returning to live in South Korea

[edit]When International Korean Adoptees turned into adults, many of them chose to return.[73] These countries include Sweden, United States of America, the Netherlands, France, and Belgium. In this respect the so-called re-Koreanization of the Korean adoptees is often reproduced in South Korean popular media (e.g. the blockbuster "Kuk'ka Taep'yo/National Representative/Take Off"). The 're-Koreanization' can be reflected in Korean ethnic based nationalism (both north and south of the 38th parallel).

A 2005 article in Hyphen: Asian America Unabridged said that an increasing number adoptees were moving back to live in South Korea to try to help other Korean adoptees, and it said that many of these returning Korean adoptees were critical of South Korea's adoption system. The article said that one returning Korean adoptee, for example, made a confrontational exhibition where he posted photos of 3,000 Korean adoptees in South Korea's three largest cities with the hope that South Koreans would see these photos and question why South Korea was still sending many Korean children abroad as adoptees. The article said that another returning Korean adoptee created an organization based in South Korea called Adoptee Solidarity Korea (ASK) to end the international adoption of South Korean orphans, and the article said that ASK intended to accomplish this goal by "preventing teenage pregnancy through sex education, monitoring orphanages and foster care, increasing domestic adoption and expanding welfare programs for single mothers." The article said that other Korean adoptees who returned to live in South Korea did volunteer work in orphanages.[74]

The article went on to say Korean adoptees who return to live in South Korea choose to use a Korean name, their adopted name or a combination of both while living in South Korea. The article said that one returning adoptee said that they chose to use a combination of both names to indicate their status as a Korean adoptee. The article said that another returning Korean adoptee chose to use a Korean name, but the name they decided to go by was one that they chose for themselves and not the Korean name which was originally assigned to them by their orphanage when they were an orphan. The article said that another returning Korean adoptee decided to go by their original Korean name over their adopted Belgian name, because their Belgian name was difficult for other people to pronounce.[74]

The article also claimed that Korean adoptees who return to live in South Korea from the United States generally hold higher paying jobs in South Korea that involve speaking English and teaching while Korean adoptees who return to live in South Korea from European countries that use other languages generally get involved with lower paying jobs in restaurants, bars and stores while living in South Korea.[74]

In 2010 the South Korean Government legalized dual citizenship for Korean adoptees, and this law that went into effect in 2011.[3]

in 2023 the group led by Peter Moller, an adoptee demanded inquiry of illegal adoptions between 1960 and 1980s to Truth and Reflection commission [75] [76][77] [78]

Adoptees deported to South Korea

[edit]A 2016 article in The Guardian said that the South Korean government had record of 10 Korean adoptees who were deported from the United States to South Korea.[79]

A 2016 article in The Nation described the story of a Korean adoptee who did not have U.S. citizenship who was deported to South Korea from the United States for committing a crime in the United States.[80]

A 2017 article in The New York Times about a Korean adoptee who was deported and is looking to make a life in South Korea does an overview of the lives of returning Korean adoptees and the difficulties they face.[81][full citation needed]

Adoptee associations

[edit]The first association to be created for adult Korean adoptees was Adopterade Koreaners Förening, founded on November 19, 1986, in Sweden.[82] In 1995, the first Korean adoptee conference was held in Germany, and, in 1999, Korean adoptee conferences were arranged in both the US and South Korea.[2]

A 2010 book about South Korean adoption estimated that ten percent of Korean adoptees who are over the age of eighteen are part of adult Korean adoptee associations.[1]

| Name | Region | Date founded | Website |

|---|---|---|---|

| International Korean Adoptee Associations | International | 2004[83] | website |

| Adopted Koreans' Association | Sweden | 1986[84] | website |

| AKConnection | Minnesota, USA | 2000[85] | website |

| Also-Known-As, Inc. | New York, USA | 1996[86] | website |

| Arierang | The Netherlands | 1991[87] | website |

| Asian Adult Adoptees of Washington | Washington, USA | 1996[88] | website |

| Korea Klubben | Denmark | 1990[89] | website |

| Racines Coréennes | France | 1995[90] | website |

| Association of Korean Adoptees-San Francisco | San Francisco, California | website | |

| Global Overseas Adoptees' Link | South Korea | 1997[91] | website |

| Boston Korean Adoptees | Massachusetts, USA | website | |

| Dongari | Switzerland | 1994[92] | website |

| Korean Canadian Children's Association | Canada | 1991[93] | website |

| Korean American Adoptee Adoptive Family Network | USA | 1998[94] | website |

Against international adoptions

[edit]A 2015 article in The Economist said that the Truth and Reconciliation for the Adoption Community of Korea (TRACK) was a lobby group of Korean adoptees that lobbied against the adoption of South Koreans by other countries.[35]

A 2016 book about South Korean adoption said that Adoptee Solidarity Korea (ASK) was an association of Korean adoptees that was committed to ending international adoption.[95]

Statistics

[edit]| Reason given | Percent | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty raising and loving adopted child like a birth child | 32.1% | ||||||||

| Families should be based on blood | 29.5% | ||||||||

| Financial burden | 11.9% | ||||||||

| Prejudice against adoption | 11.4% | ||||||||

| Source: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs[96] | |||||||||

| Receiving state/territory | 2001–2002 | 2002–2003 | 2003–2004 | 2004–2005 | 2005–2006 | 2006–2007 | 2007–2008 | 2008–2009 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australian Capital Territory | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 23 |

| New South Wales | 25 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 18 | 16 | 7 | 14 | 161 |

| Northern Territory | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 14 |

| Queensland | 15 | 16 | 18 | 19 | 15 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 108 |

| South Australia | 20 | 24 | 19 | 12 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 93 |

| Tasmania | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 17 |

| Victoria | 12 | 20 | 20 | 23 | 16 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 121 |

| Western Australia | 12 | 10 | 14 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 62 |

| Total | 92 | 108 | 108 | 99 | 69 | 48 | 40 | 35 | 599 |

| Source: Australian InterCountry Adoption Network[97] | |||||||||

| Primary countries (1953–2008) | Other countries (1960–1995) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Period | Adoptees | Country | Period | Adoptees | |

| United States | 1953–2008 | 109,242 | New Zealand | 1964–1984 | 559 | |

| France | 1968–2008 | 11,165 | Japan | 1962–1982 | 226 | |

| Sweden | 1957–2005 | 9,051 | Okinawa | 1970–1972 | 94 | |

| Denmark | 1965–2008 | 9,297 | Ireland | 1968–1975 | 12 | |

| Norway | 1955–2008 | 6,295 | Poland | 1970 | 7 | |

| Netherlands | 1969–2003 | 4,099 | Spain | 1968 | 5 | |

| Belgium | 1969–1995 | 3,697 | China | 1967–1968 | 4 | |

| Australia | 1969–2008 | 3,359 | Guam | 1971–1972 | 3 | |

| Germany | 1965–1996 | 2,352 | India | 1960–1964 | 3 | |

| Canada | 1967–2008 | 2,181 | Paraguay | 1969 | 2 | |

| Switzerland | 1968–1997 | 1,111 | Ethiopia | 1961 | 1 | |

| Luxembourg | 1984–2008 | 561 | Finland | 1984 | 1 | |

| Italy | 1965–2008 | 383 | Hong Kong | 1973 | 1 | |

| United Kingdom | 1958–1981 | 72 | Tunisia | 1969 | 1 | |

| Turkey | 1969 | 1 | ||||

| Other | 1956–1995 | 113 | ||||

| There were 163,898 total adoptees for primary and other countries. | ||||||

| Intercountry adoptions out of South Korea from 1953 to 2008 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total | Year | Total | Year | Total | Year | Total | Year | Total | Year | Total | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1960 | 638 | 1970 | 1,932 | 1980 | 4,144 | 1990 | 2,962 | 2000 | 2,360 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1961 | 660 | 1971 | 2,725 | 1981 | 4,628 | 1991 | 2,197 | 2001 | 2,436 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1962 | 254 | 1972 | 3,490 | 1982 | 6,434 | 1992 | 2,045 | 2002 | 2,365 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1953 | 4 | 1963 | 442 | 1973 | 4,688 | 1983 | 7,263 | 1993 | 2,290 | 2003 | 2,287 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1954 | 8 | 1964 | 462 | 1974 | 5,302 | 1984 | 7,924 | 1994 | 2,262 | 2004 | 2,258 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1955 | 59 | 1965 | 451 | 1975 | 5,077 | 1985 | 8,837 | 1995 | 2,180 | 2005 | 2,010 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1956 | 671 | 1966 | 494 | 1976 | 6,597 | 1986 | 8,680 | 1996 | 2,080 | 2006 | 1,899 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1957 | 486 | 1967 | 626 | 1977 | 6,159 | 1987 | 7,947 | 1997 | 2,057 | 2007 | 1,264 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1958 | 930 | 1968 | 949 | 1978 | 5,917 | 1988 | 6,463 | 1998 | 2,443 | 2008 | 1,250 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1959 | 741 | 1969 | 1,190 | 1979 | 4,148 | 1989 | 4,191 | 1999 | 2,409 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1953–1959 Total 2,899 |

1960–1969 Total 6,166 |

1970–1979 Total 46,035 |

1980–1989 Total 66,511 |

1990–1999 Total 22,925 |

2000–2008 Total 18,129 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| There was a total of 162,665 overseas adoptions out of South Korea from 1953 to 2008. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| colspan="18" | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Year | Total | US | Sweden | Canada | Norway | Australia | Luxemburg | Denmark | France | Italy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 1,264 | 1,013 | 80 | 68 | 20 | 44 | 3 | 22 | 14 | - | |

| 2008 | 1,250 | 988 | 76 | 78 | 45 | 18 | 16 | 20 | 8 | 1 | |

| 2009 | 1,125 | 850 | 84 | 67 | 40 | 34 | 17 | 21 | 8 | 4 | |

| 2010 | 1,013 | 775 | 74 | 60 | 43 | 18 | 12 | 21 | 6 | 4 | |

| 2011.6 | 607 | 495 | 26 | 27 | 20 | 17 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 2 | |

| By year | Total | Before 2000 |

2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011.6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 39,540 | 33,812 | 757 | 843 | 669 | 712 | 764 | 725 | 540 | 153 | 133 | 252 | 180 |

| Home | 476 | 197 | 14 | 16 | 20 | 7 | 27 | 12 | 40 | 29 | 36 | 47 | 31 |

| Abroad | 39,064 | 33,615 | 743 | 827 | 649 | 705 | 737 | 713 | 500 | 124 | 97 | 205 | 149 |

| Source: Ministry of Health and Welfare[98] | |||||||||||||

| Category | Total | Before 2004 |

2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011.6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Total | 239,493 | 221,190 | 3,562 | 3,231 | 2,652 | 2,556 | 2,439 | 2,475 | 1,388 | |||

| Home | 75,190 | 66,146 | 1,461 | 1,332 | 1,388 | 1,306 | 1,314 | 1,462 | 781 | ||||

| Abroad | 164,303 | 155,044 | 2,101 | 1,899 | 1,264 | 1,250 | 1,125 | 1,013 | 607 | ||||

| Source: Ministry of Health and Welfare[98] | |||||||||||||

| Year | Domestic adoption | International adoption | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Single mother's child |

Child under facility care |

Child from broken family etc. |

Total | Single mother's child |

Starvation etc. |

Child from broken family | ||

| 2007 | 1,388 | 1,045 | 118 | 225 | 1,264 | 1,251 | 11 | 2 | |

| 2008 | 1,306 | 1,056 | 86 | 164 | 1,250 | 1,114 | 10 | 126 | |

| 2009 | 1,314 | 1,116 | 70 | 128 | 1,125 | 1,005 | 8 | 112 | |

| 2010 | 1,462 | 1,290 | 46 | 126 | 1,013 | 876 | 4 | 133 | |

| 2011.6 | 781 | 733 | 22 | 26 | 607 | 537 | 8 | 62 | |

| Source: Ministry of Health and Welfare[98] | |||||||||

| Year | Abandoned | Broken home | Single mother | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1958–1960 | 1,675 | 630 | 227 | 2,532 | |||||

| 1961–1970 | 4,013 | 1,958 | 1,304 | 7,275 | |||||

| 1971–1980 | 17,260 | 13,360 | 17,627 | 48,247 | |||||

| 1981–1990 | 6,769 | 11,399 | 47,153 | 65,321 | |||||

| 1991–2000 | 255 | 1,444 | 20,460 | 22,129 | |||||

| 2001 | 1 | 1 | 2,434 | 2,436 | |||||

| 2002 | 1 | 0 | 2,364 | 2,365 | |||||

| 2003 | 2 | 2 | 2,283 | 2,287 | |||||

| 2004 | 0 | 1 | 2,257 | 2,258 | |||||

| 2005 | 4 | 28 | 2,069 | 2,101 | |||||

| 2006 | 4 | 5 | 1,890 | 1,899 | |||||

| 2007 | 11 | 2 | 1,251 | 1,264 | |||||

| 2008 | 10 | 126 | 1,114 | 1,250 | |||||

| Total | 29,975 | 28,956 | 102,433 | 161,364 | |||||

| Source: South Korean Ministry of Health, Welfare and Family Affairs 2009[1] | |||||||||

| Year | Total | Substitute family care |

Foster care by relatives |

General foster care | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of households |

No. of children |

No. of households |

No. of children |

No. of households |

No. of children |

No. of households |

No. of children | ||

| 2006 | 10,253 | 14,465 | 6,152 | 9,062 | 3,097 | 4,160 | 1,004 | 1,243 | |

| 2007 | 11,622 | 16,200 | 6,975 | 10,112 | 3,651 | 4,850 | 996 | 1,238 | |

| 2008 | 11,914 | 16,454 | 7,488 | 10,709 | 3,436 | 4,519 | 990 | 1,226 | |

| 2009 | 12,170 | 16,608 | 7,809 | 10,947 | 3,438 | 4,503 | 923 | 1,158 | |

| 2010 | 12,120 | 16,359 | 7,849 | 10,865 | 3,365 | 4,371 | 906 | 1,123 | |

| Source: Ministry of Health and Welfare[98] | |||||||||

| Year | No. of facilities |

No. of children | No. of employees | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | |||||||

| 2006 | 1,030 | ||||||||

| 2007 | 276 | 1,368 | 745 | 623 | 623 | ||||

| 2008 | 348 | 1,664 | 884 | 780 | 754 | ||||

| 2009 | 397 | 1,993 | 1,076 | 917 | 849 | ||||

| 2010 | 416 | 2,127 | 1,125 | 1,002 | 894 | ||||

| Source: Ministry of Health and Welfare[98] | |||||||||

| Year | Gender | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | |

| 2006 | 18,817 | 10,789 | 8,028 |

| 2007 | 18,426 | 10,563 | 7,863 |

| 2008 | 17,992 | 10,229 | 7,763 |

| 2009 | 17,586 | 10,105 | 7,481 |

| 2010 | 17,119 | 9,790 | 7,329 |

| Source: Ministry of Health and Welfare[98] | |||

| Year | Adopted Koreans |

Year | Adopted Koreans |

Year | Adopted Koreans | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 1,994 | 2007 | 938 | 2015 | 318 | ||

| 2000 | 1,784 | 2008 | 1,064 | ||||

| 2001 | 1,862 | 2009 | 1,079 | ||||

| 2002 | 1,776 | 2010 | 865 | ||||

| 2003 | 1,793 | 2011 | 736 | ||||

| 2004 | 1,713 | 2012 | 627 | ||||

| 2005 | 1,628 | 2013 | 138 | ||||

| 2006 | 1,373 | 2014 | 370 | ||||

| Source: Bureau of Consular Affairs[99] | |||||||

| Adoptive parents | ||

|---|---|---|

| Adoptive Caucasian mother | 98% | |

| Adoptive Caucasian father | 97% | |

| Neighborhood growing up | ||

| Neighborhood was only Caucasian | 70% | |

| Neighborhood included other Asians | 15% | |

| Neighborhood included non-Asian non-Caucasians | 13% | |

| Friends growing up | ||

| Friends were only Caucasian | 55% | |

| Had Asian friends | 24% | |

| Had non-Asian non-Caucasian friends | 19% | |

| Siblings | ||

| Other Korean adopted siblings | 52% | |

| Biological children of adoptive parent | 26% | |

| Respondent was the only child | 13% | |

| Domestically adopted siblings | 7% | |

| Internationally adopted, non-Korean siblings | 3% | |

| Race of spouse | ||

| Spouse | Korean men | Korean women |

| Caucasian | 50% | 80% |

| Asian | 50% | 13% |

| African-American | 0% | 3% |

| Latino | 0% | 3% |

| View of own ethnicity during childhood and adolescence | ||

| Caucasian | 36% | |

| Korean-American or Korean-European | 28% | |

| American or European | 22% | |

| Asian or Korean | 14% | |

| View of own ethnicity as adults | ||

| Korean-American or Korean-European | 64% | |

| Asian or Korean | 14% | |

| Caucasian | 11% | |

| American or European | 10% | |

| Korean heritage exploration method | ||

| Activity | Growing up | As adults |

| Korean and/or adoptee events and organizations | 72% | 46% |

| Book/study | 22% | 40% |

| Korean friends or contacts | 12% | 34% |

| Korean food | 12% | 4% |

| Travel to South Korea | 9% | 38% |

| Korean language study | 5% | 19% |

| Status of search for birth family | ||

| Interested in searching | 34% | |

| Not Interested in searching | 29% | |

| Have searched or are searching | 22% | |

| Uncertain if interested in searching | 15% | |

| Reason for search for birth family | ||

| Obtain medical histories | 40% | |

| Curiosity | 30% | |

| Meet people who look like them | 18% | |

| Learn reason they were given up for adoption | 18% | |

| Learn if they have relatives, especially siblings | 16% | |

| Fill void or find closure | 16% | |

| Send message to birth parents | 10% | |

| Source: The Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute[50] | ||

| Placement before adoption | ||

|---|---|---|

| Orphanage | 40.9% | |

| Foster care | 40.3% | |

| Did not know | 9.1% | |

| Birth family | 8% | |

| Other living arrangement than ones listed |

1.7% | |

| Reason for separation from biological family | ||

| Did not know | 46% | |

| Did know (39%) |

Single-parent household | 21% |

| Poverty | 18% | |

| Lost child accidentally separated from family who were not found |

4% | |

| Death in the family | 4% | |

| Placed for adoption by non-parent family member possibly indicating birth parent(s) did not decide to relinquish |

4% | |

| Abuse in birth family | 1% | |

| Did not respond to the question | 15% | |

| Source: IKAA Gathering 2010 Report[100] | ||

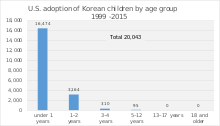

1999 to 2016 US adoptees

[edit]From 1999 to 2015, there have been 20,058 Koreans adopted by US families. Of these 20,058 children, 12,038 (about 60%) have been male and 8,019 (about 40%) have been female. Of these 20,058 children, 16,474 were adopted when they were less than one year old, 3,164 were adopted when they were between one and two years old and 310 were adopted when they were between three and four years old. Of these 20,058 children, 19,222 of them immigrated to the United States using the IR-4 Immediate Relative Immigrant Visa, and 836 of them immigrated to the United States using the IR-3 Immediate Relative Immigrant Visa.[99]

Individual Korean adoptees

[edit]Works of Korean adoptees have become known both in art, literature and film-making. Other Korean adoptees have received celebrity status for other reasons, like Soon-Yi Previn who is married to Woody Allen, actresses Nicole Bilderback and Jenna Ushkowitz, model and actress Beckitta Fruit, Washington State Senator Paull Shin, former Slovak rap-artist Daniel Hwan Oostra, Kristen Kish of Top Chef Season 10, make-up artist turned content creator Claire Marshall,[101] former French minister Fleur Pellerin and professional baseball player Rob Refsnyder. The 2015 documentary film Twinsters covers the life of Korean adoptees Samantha Futerman and Anaïs Bordier who were separated at birth and reconnected online and meeting in real life.

Joy Alessi

[edit]A 2016 article in The Hankyoreh covered the story of Korean adoptee Joy Alessi. Alessi was put in a South Korean orphanage in Munsan on July 20, 1966, a day or two after being born, and she was adopted in the United States through Holt Children's Welfare Association when she was seven months old. Alessi found out that she was not a US citizen when she was 25 years old after trying to apply for a US passport and being unable to obtain one due to not being a US citizen. Alessi was ultimately able to get a South Korean passport after some difficulties. Alessi needed to present her South Korean passport, adoption documents and describe her situation in order to get a job, and she obtained a job as a flight attendant. Alessi returned to South Korea when she was 49 years old, and she tried to find her birth parents in South Korea, but she was not able to find them.[102]

Sivan Almoz

[edit]Born in South Korea in the 1960s, Sivan Almoz was found abandoned by an orphanage soon after her birth. She spent three years at an orphanage before being adopted by an Israeli couple.

Almoz went on to become a social worker, and co-founded the "First Hug" association which trains and dispatched volunteers that care for babies abandoned at Israeli hospitals.

In an interview, she has stated that when she turned 18, the age at which she is entitled to access information and documentation related to her adoption according to law, she has decided instead to "adopt my non-biological parents". She has never searched for her birth parents.[103]

Hojung Audenaerde

[edit]A 2017 article in Yonhap covered the story of Korean adoptee Hojung Audenaerde. The article said that Audenaerde was twenty-seven months old when her birth father gave her up for adoption. Audenaerde was adopted by a Belgian couple who moved to the United States. Audenaerde's adoption agency found her birth father, because Audenaerde's documentation was intact and correct. Audenaerde communicated with her birth father by exchanging letters which led to Audenaerde finding her partially paralyzed birth mother with whom she had her first meeting in 2014.[104]

Marissa Brandt

[edit]A 2017 article in The New York Times said that Korean adoptee Marissa Brandt, who was adopted by an American family, was a defenceman on South Korea women's national ice hockey team, and the article said that she wore her Korean name, Park Yoon-jung, on her hockey jersey.[105]

Cyndy Burns

[edit]A 2016 article on the CBS News website covered the story of Korean adoptee Cyndy Burns who was left at an adoption agency when she was ten months old. Burns had grown up in Connecticut. Burns used a DNA sample to find her birth mother, Sun Cha, who had been living in the United States, and Burns went to Tacoma, Washington to meet her birth mother.[106]

Phillip Clay

[edit]A 2017 article in The Philadelphia Inquirer covered the story of Korean adoptee Phillip Clay who was adopted in 1983 to a couple in Philadelphia when he was 8 years old. Not having US citizenship and having a long criminal record, Clay was deported in 2012 to South Korea. For the next five years, Clay struggled to speak Korean and form connections with other Korean adoptees. On May 21, 2017, Clay committed suicide by jumping from the 14th floor of a building in Ilsan.[107]

Thomas Park Clement

[edit]A 2015 article in The Washington Times said that mixed-race Korean adoptee Thomas Park Clement who was born during the middle of the Korean War remembered being abandoned by his birth mother when he was four and half years old after Clement's birth mother told him to walk down a street and not turn around. Clement lived on the streets before being put in an orphanage. Two years after, Clement was adopted by a family in North Carolina. Clement later received a degree in electrical engineering from Purdue University, and Clement founded Mectra Labs, a medical device company, in 1988. Clement was not planning on looking for his birth mother.[108]

A 2013 article in The Berkshire Eagle said that Clement's 2012 biography was called Dust of the Streets: The Journey of a Biracial Orphan of the Korean War.[109]

A 2016 article in The Seattle Times said that Korean adoptee Thomas Park Clement founded Mectra Labs which is a medical-manufacturing company, and it said that Clement has pledged $1,000,000 worth of DNA testing kits for donation. Clement has given 2,550 DNA testing kits to Korean adoptees and Korean War veterans, and he has given 450 DNA testing kits to 325Kamra which is a volunteer organization to give to people in South Korea. Clement said, "I have throughout the years experienced so many of my fellow Korean adoptees' frustrations with birth-relative searches", and Clement said, "DNA is shortcutting the search process and bringing all parties in direct communication with each other."[110]

A 2015 article on the Public Radio International website said that Clement was paying for the DNA kits from 23andMe.[111]

Adam Crapser

[edit]A 2016 article on the Q13 Fox website said that Immigration Judge John O'Dell chose to deport Adam Crapser, a Korean adoptee who was not a US citizen, due to Crapser's criminal record.[112]

Kyung Eun Davidson

[edit]A 2016 article in The Korea Herald covered the story of Korean adoptee Kyung Eun Davidson. The article said that Davidson was a Korean adoptee who was given up for adoption when she was three years old by her birth father. Davidson grew up in Oregon after being adopted. Davidson was in Korea from 2005 to 2007 to find her birth mother. Davidson reunited with her birth father in 2007, but after their first reunion he disappeared. Davidson went back to the United States from Korea in 2007. Davidson's birth father had lied to her birth mother that he had been raising her for more than twenty years when in reality he had put her up for adoption. Davidson's birth mother went to Holt in 2008 after Davidson's birth mother found out about her biological daughter being put up for adoption by Davidson's birth father. Davidson became aware that her birth mother did not relinquish her for adoption in 2016. Davidson found her birth mother through a DNA match, and Davidson and her birth mother were going to meet each other in person.[113]

Amy Davis

[edit]A 2017 article in the Duluth News Tribune covered the story of Korean adoptee Amy Davis. Davis was adopted in the 1970s, and Davis grew up in Cloquet, Minnesota, in a community of mostly white people. Davis's adoptive parents were told that Davis had been abandoned, so there was no way to contact Davis's birth parents. In 2016, Davis went to Korea to search for her birth parents, and Davis's case manager told Davis that her biological aunt had been looking for her seven years ago. Davis's case manager originally did not tell Davis the name of her biological aunt, because it was against Korea's privacy laws for the case manager to tell Davis this information, but the case manager eventually broke the law and told Davis the information. Davis found her biological aunt, and Davis found her birth father who was proven to be her birth father through DNA testing. Davis's birth parents had split up when Davis was one year old, and Davis's birth father had been leaving Davis with his mother (Davis's biological grandmother) while Davis's birth father went to work. Davis had long thought that she was abandoned in a police station, but, in reality, it was her biological grandmother who had put her up for adoption without her birth parents' consent or awareness, and this act had caused her birth family to become estranged. Davis's 97-year-old biological grandmother asked for forgiveness for what she had done to Davis, and Davis forgave her.[114]

Karen Hae Soon Eckert

[edit]A 2000 article on the PBS website covered the story of Korean adoptee Karen Hae Soon Eckert. Eckert was discovered at a police station in Seoul on February 21, 1971, with no accompanying written information left with her. Because she had no written information left with her, she was given the name Park Hae-soon. Officials estimated Eckert's birthday to be February 12, 1971, because they said that she looked about 10 days old. Eckert was in a hospital for four months after she was born before being put in Holt International's foster care. When Eckert was 9 months old, she was adopted, and she grew up in Danville, California. Eckert's brothers and parents were white people. Five years after she was eighteen years old, Eckert joined a group of adult adoptees. Eckert liked encountering other adoptees, she liked sharing experiences and she liked being able to empathize.[115]

Layne Fostervold

[edit]A 2017 article on the PRI website covered the story of Korean adoptee Layne Fostervold. Fostervold's birth mother, Kim Sook-nyeon, was unwed when she became pregnant with Fostervold in 1971, and Kim Sook-nyeon's family would have encountered a lot of stigma and prejudice if she had kept Fostervold. Fostervold was adopted when he was 2 years old, and Fostervold grew up in Willmar, Minnesota. Fostervold said that he had the feeling for almost all of his life that his birth mother did not want to give him up for adoption. Kim Sook-nyeon said that she had to promise not to go looking for Fostervold in the future. Kim Sook-nyeon said that she had prayed for Fostervold, worried about Fostervold and wanted Fostervold to have a good life. Fostervold went to Korea in 2012, and he talked to Korea Social Service (KSS) which was the agency which had done his adoption. A social worker for KSS told Fostervold that a person who claimed to be his birth mother looked for him in 1991 and 1998, but nobody from KSS had told his adoptive family this information. Fostervold reunited with his birth mother. Fostervold moved to South Korea in 2016, and Fostervold was living with his birth mother in 2017. Fostervold was trying to learn the Korean language in order to obtain a professional job, and Fostervold changed his last name from Fostervold back to Kim on social media.[116]

Steven Haruch

[edit]A 2000 article on the PBS website covered the story of Korean adoptee Steven Haruch. The story was that Haruch was born in Seoul in 1974, and Haruch was given the name Oh Young-chan by the strangers who took care for him until Haruch went to the United States in 1976. Haruch was adopted to a white family and most of the people around him were white too. In high school and college, Haruch wrote self-pitying poems about being adopted. In 2000, Haruch was the Acting Instructor in the Department of English in University of Washington. Haruch wrote film criticism for the Seattle Weekly, and Haruch was a part-time teacher at a Korean-American after-school program.[117]

Shannon Heit

[edit]A 2014 article in MinnPost covered the story of Korean adoptee Shannon Heit. Heit was on K-pop Star in 2008 for the purpose of trying to find her birth mother who she believed had given her up for adoption more than twenty years ago. Heit's appearance on TV and Heit's singing ability led to her being reunited with her birth mother. Heit learned that she had been put up for adoption by her biological grandmother when her birth mother was away working which was contrary to the story her adoptive family had been told. Heit was supportive of the Special Adoption Law which went into effect in August 2012. In 2014, Heit was living in South Korea, was married and was working as an editor and translator. Also in 2014, Heit was working with civic groups to help unwed mothers and she was counseling adopted children. Heit remained in contact with her adoptive parents in the United States, and Heit said, "my case shows how traumatic adoption can be, even when the adoptive parents are loving and have the best intentions."[118]

Sara Jones

[edit]Born in South Korea in the 1970s, Sara's father made the tough decision to place her in an orphanage in order to ensure she received the care she deserved. Prior to placing her in the orphanage, her father gave each member of his family a special tattoo.

At the age of 3, Sara was adopted by a white family from Utah, USA. Her new parents relocated her to Utah, gave her a new name, and had her mysterious tattoo removed. She was then raised as the only minority in a predominantly white community. As a result of her upbringing, Sara identified more with being a White female than an Asian female. Sara went on to graduate with honors from The University of Utah with a B.S. in chemical engineering, graduate cum laude from Brigham Young University, become a female CEO, and co-founded the Women's Tech Council.

Despite her success, Sara yearned to find her birth family and embrace her Asian heritage. She used modern resources and her mysterious tattoo to begin the search for her birth family. 42 years after she was adopted, Sara was reunited with her birth family. She now uses her unique experience of being a Korean adoptee, growing up a minority in a predominately white community, reuniting with her birth family, and being a female leader working in a field dominated by white males to help others. Most recently, she was featured by Ted.com for her 2019 TedxSaltLakeCity talk entitled "My Story of Love and Loss as a Transracial Adoptee".

Sara is currently the CEO of InclusionPro, a consulting firm specializing in helping organizations create inclusive work environments. She has keynoted the Silicone Slopes Tech Summit as well as being featured in numerous articles, publications, and podcasts. As a result of her work, Sara received a Distinguished Alumna award from the University of Utah College of Engineering. Other awards she has received include CEO of the year, being honored as a Women to Watch, and receiving the Utah Innovation award.[119][120][121][122][123]

Dong-hwa Kim